Evictions: ‘This is a symptom of a greater problem.’

[highlightrule] Thousands of people are evicted in Mecklenburg County each year. Some find new homes, but many turn to couch-surfing, or motels or shelters, caught in a cycle of rising rents, stagnant wages and the cascading effects eviction can have on a family’s financial well-being.[/highlightrule]

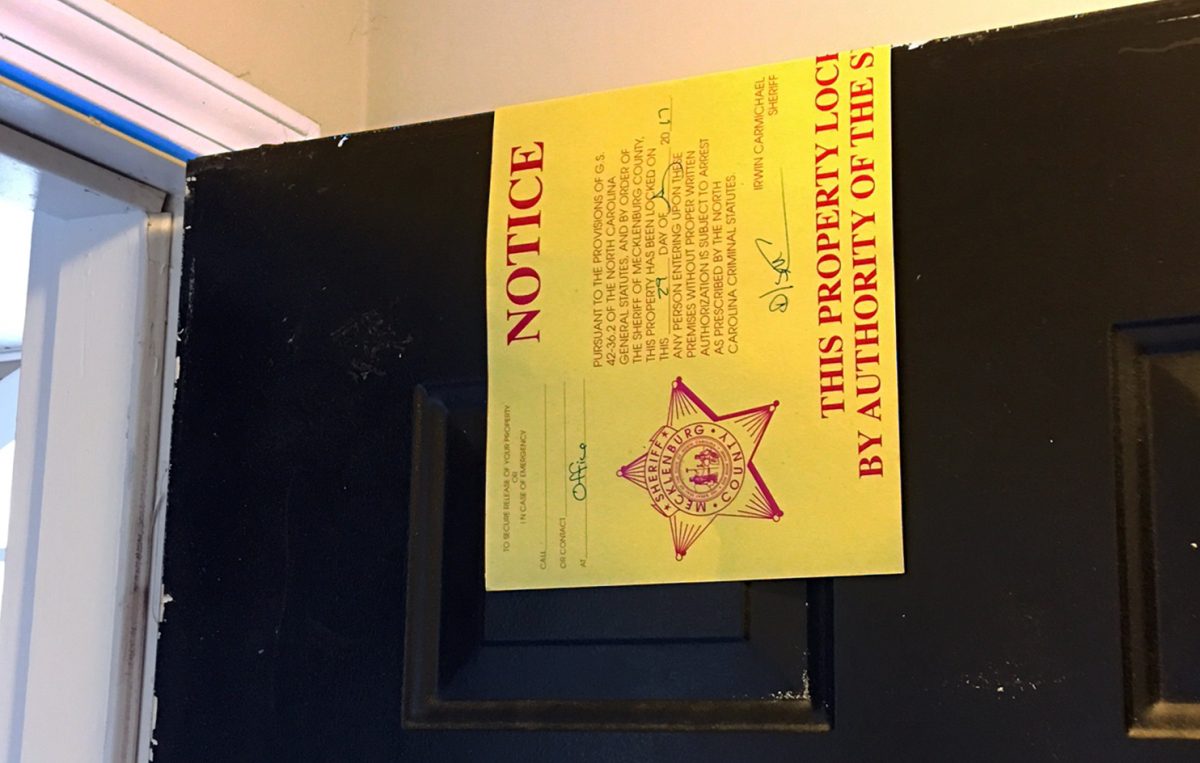

A pink backpack lies on the sofa. Leaning on a wall are two children’s scooters. Bags of possessions are scattered around the mostly empty apartment, and some food on the counter. Drills whirr loudly as workers change the lock while Mecklenburg County sheriff’s deputy Mitch Adams hangs a yellow cardboard sign over the door:

“Notice. This Property Locked By Authority Of The Sheriff.”

The tenant, a divorced mother of five we’ll call Candace, is being “padlocked”– evicted from her home for not paying the rent.

She drives up in a white van, returning for the last of her things from the three-bedroom apartment in southwest Charlotte. She knew this was coming; she is attending school and working, but her $10.50-an-hour part-time job can’t pay the rent. She says she tried to plan for the loss of her home but hasn’t been accepted at the Salvation Army’s Center of Hope shelter for women and children. For now, Candace and her kids will stay with her sister – in violation of the sister’s lease.

She is one of thousands of Charlotte residents evicted each year. Some find new housing, often worse or in a worse neighborhood. Many, as she will do, double up with relatives or friends. Others stay in motels or sleep in cars. Their difficulties are a byproduct of larger problems in Charlotte: low-wage jobs, housing increasingly unaffordable to lower wage workers, a legal process that can put tenants at a disadvantage, and a housing services system that, for lack of shelter beds, prioritizes people who have no other place to go.

* * * * *

|

CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG EVICTIONS REPORT The UNC Charlotte Urban Institute and Mecklenburg County Community Support Services released a report Monday, Sept. 25, looking at evictions in the county. It is the first of three reports on the topic. |

Until 2008 when Matthew Desmond, then a Ph.D. student at University of Wisconsin, moved into a Milwaukee trailer park to study evictions, little research had gone into the phenomenon and the ways it disrupts lives. By 2016 Desmond’s research had become his best-selling, Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City. Desmond spoke Wednesday to a sold-out audience in Charlotte. (A livestream viewing of Desmond’s presentation took place simultaneously at Christ Lutheran Church in Charlotte.)

The book hit at a significant time for Charlotte. In 2013, news broke that the city was 50th of 50 large city regions in a study from scholars at Harvard and UC Berkeley examining upward economic mobility among children in low-income families. Charlotte’s nonprofit, government and business leaders convened a wide-ranging initiative to look at the problem and recommend action. Eviction, per se, wasn’t one of the headlines in the report the group released in March, although it found child and family stability was one of three determinants of success. Brian Collier of the Foundation For The Carolinas, a major backer of the initiative, says, “We looked at housing as a key part of family stability. … It’s connected to all these other things that are related to economic mobility.”

And rising rents along with stagnant median incomes make paying the rent harder and harder for more Charlotte families. To illustrate, in Mecklenburg County from 2010 to 2015, median gross rent rose approximately 11 percent while median household income rose only about .3 percent, from $56,716 to $56,883.

Housing experts consider households spending 30 percent or more of gross income on rent to be “cost-burdened.” In Mecklenburg County in 2015, an estimated 45 percent of renters – 79,252 households – spent more than a third of their gross income on housing, and 22 percent are spending half or more on rent.

Desmond’s book traces the lives of eight families and their landlords in two low-income Milwaukee neighborhoods. As tenants move from place to place, he shows how evictions affect more than just someone’s address. Some costs are intangible – like the loss of stability for children who change schools, lose their home and sometimes move in and out of shelters. Other costs are financial, with cascading problems that can include paying late fees, eviction court costs, new apartment and utility deposits, repeated loss of possessions and sometimes the cost to move or store possessions to avert loss. Hunting for new housing or moving can mean missing work or losing a paycheck or a job. Repeated financial setbacks hinder a family’s wherewithal to build any nest egg or move out of poverty.

Picture the causes and conditions of poverty as a large puzzle. Interlocking with other pieces such as homelessness, instability, exploitation and despair is this piece – eviction.

A full waiting room at Crisis Assistance Ministry, which offers emergency help to people with housing or other types of financial crisis. Photo: Nancy Pierce

A full waiting room at Crisis Assistance Ministry, which offers emergency help to people with housing or other types of financial crisis. Photo: Nancy Pierce

MILLIONS SPENT TO AVERT – FOR A TIME – FAMILY CRISIS

One warm morning in August, the Crisis Assistance Ministry lobby north of uptown was, as usual, filled. As the doors opened at 8, people who had lined up streamed in, heading to one of several windows depending on their needs. Staff logged client information into computers and scheduled visits with caseworkers.

Although the public may not pay much attention to eviction’s impact, it’s not news to the nonprofit Crisis Assistance, which offers help and advocacy for people in financial crisis. In each of the past two years it paid out almost $2.8 million in emergency rental assistance, helping some 5,300 households in 2016.

On this morning, a neatly dressed man in his mid-40s sits in a small office to talk to caseworker Diana Walker. He and Crisis Assistance have agreed to let me observe if he is not identified. Contrary to what some people may assume about people in financial crisis, it’s his first visit to Crisis Assistance. He is not homeless. He has a master’s degree, earned online, and for a time was getting student aid. His monthly expenses are minimal: $850 rent, utilities, $60 for a cellphone. No cable, internet or car payment. To get around he uses public transportation or gets a ride. He cuts his own hair. His son lives with him during the school year. He gets food stamps; his son gets Medicaid.

One reason his situation is tough: “I am an ex-felon.” He got in trouble at 21, serving two years in prison in Pennsylvania. “Crack,” he says. Since 1997 he hasn’t gotten in any trouble, he says, “but it’s been hard to get a job.”

Now he has found a job, or at least the hope of one. Out-of-town training starts the next week; he paid $180 for drug tests and permits. Meanwhile his University City-area apartment management notified him: Pay rent by 10 a.m. today or they’ll go to court to evict him. He owes $963, which he can’t pay.

[highlight]“This is a symptom of a greater problem.” — Carol Hardison, CEO of Crisis Assistance Ministry [/highlight]

Later, Crisis Assistance CEO Carol Hardison reflects on the agency’s role and what its clients’ needs say about the larger community. “Eviction and utility disconnections are actually affordable transportation, affordable child care and affordable housing problems,” she says. “It just shows up as a rent and utilities problem. This is a symptom of a greater problem.”

In addition to rental assistance, the agency offers assistance to avert utility shutoffs, among other services. In 2016, the tally for the rental and utility assistance it offered was $7.81 million for 12,917 households. Hardison sees utility assistance as closely related to eviction prevention, since a common reason people don’t pay utility bills is so they can pay rent.

“This is the Charlotte affordable housing problem right here,” she says.

The man in Diana Walker’s office waits as she arranges for a voucher for $600 of the $963 he owes. Crisis Assistance has to make its funds last all year and can’t give all clients what they ask for. She offers a referral to Good Friends, a fund available at the Department of Social Services and similar to the Good Fellows fund, which can be administered at Crisis Assistance. The Good Friends assessment takes place at an office some 5 miles away. Maybe he can get the rest of what he owes there.

COMPLETE EVICTION NUMBERS ARE ELUSIVE

It’s difficult to determine precisely how many people get evicted in Mecklenburg County, because the available statistics don’t paint a complete picture. The UNC Charlotte Urban Institute looked at state court filing data and Mecklenburg County Sheriff’s Office reports. Even more elusive is to learn where evicted tenants go.

Formal eviction is a legal process that typically starts in small claims court, with a magistrate presiding. Landlords seeking to evict a tenant file a Complaint in Summary Ejectment. A tenant may be legally evicted for not paying rent, violating the lease, criminal activity or simply if the lease has ended. If the owner wants to sell the property for redevelopment – as is happening more often in fast-growing Charlotte – tenants are likely to lose their homes.

Legal eviction can take a month or more. Depending on the lease, there’s typically a grace period after the rent is due, often five days and sometimes as much as 10 days. Then the landlord can file a complaint in summary ejectment, and a court hearing is set. The Mecklenburg County Sheriff’s Office notifies tenants at least two days before the hearing. If a magistrate orders eviction there is a 10-day period when a tenant can appeal. An appeal costs $150, which can be waived for indigence.

If a magistrate orders an eviction, over the next several days records move from courtroom to clerk of court, and – after the landlord files a “writ of possession” if the tenant hasn’t paid rent or departed – to the sheriff’s office. At that point the padlocking must occur within seven days.

The whole process usually takes about 45 days, says Scott Wilkerson, a long-time apartment management executive who is chief investment officer at Ginkgo Residential. “The last thing we want to do is file an eviction.”

Court records show 28,471 eviction complaints filed in Mecklenburg County small claims court during the 2015-16 fiscal year (July 1-June 30). Although that’s the most of any N.C. county, since Mecklenburg is the most populous, if you measure evictions filed per rental household, Mecklenburg ranks ninth.

Evictions aren’t just a city problem. The highest N.C. eviction rates per rental household are in Eastern North Carolina’s Nash, Edgecombe, Vance and Wilson counties. Among urban counties, Guilford (Greensboro), Durham and Forsyth (Winston-Salem) lead Mecklenburg.

Source: UNC Charlotte Urban Institute analysis of N.C. Court VCAP Data and 2011-2015 American Community Survey 5-year estimates

Court numbers don’t show how many tenants depart before a case even begins – what’s called an informal eviction. Sometimes tenants don’t want an eviction on their record. That can make finding new housing harder. Sometimes they don’t know their legal rights. Desmond notes that landlords sometimes offer a tenant a few hundred dollars to just leave.

In Mecklenburg County the number of eviction complaints filed during the 2015-16 fiscal year is down from 39,173 in 2010-11. The numbers don’t allow for a definitive conclusion why, but the slowly improving economy after the recession is likely one reason.

Court records show 61 percent of Mecklenburg’s initial eviction complaints in 2015-16 were wholly or partly granted. But not all those end with tenants out of a home. Sometimes even after a magistrate grants a writ of possession, meaning a landlord can lock out the tenant, the tenant pays and gets to stay. Of all the eviction complaints filed, roughly a third end with a writ of possession to be served by the county sheriff’s office, according to sheriff’s office data from 2005-06 to 2014-15.

Source: UNC Charlotte Urban Institute analysis of N.C. Court VCAP Data and 2011-2015 American Community Survey 5-year estimates

WHO IS AFFECTED?

Court records don’t show gender, race and ethnicity, income or whether the household has children.

Crisis Assistance Ministry keeps records of its clients, including by gender and race, although its records are just one slice of the overall picture. Many people facing eviction don’t visit that agency.

In calendar year 2015, the nonprofit interviewed 1,068 clients who had been ordered padlocked, or an average of 90 a month. For 2016 that number was 817, or 68 a month. Most heads of households that the agency sees who face padlocking are black (89 percent) and female (about 70 percent). That compares to the overall Mecklenburg population, which is 31 percent black and 53 percent female.

Map shows 2015 numbers. Mouse over the map to see data from 2015 and 2016. Zip codes where 5 or fewer were reported are shown as blank. Source: Crisis Assistance Ministry

Clients at Crisis Assistance overall, not just those facing eviction, tend to have earned income (63 percent) and a high school diploma (86 percent). Fifty-eight percent have children in the home; two-thirds are single-parent households.

That echoes what Matthew Desmond learned in his Milwaukee eviction research. In Evicted, he writes: “If incarceration had come to define the lives of men from impoverished black neighborhoods, eviction was shaping the lives of women. Poor black men were locked up. Poor black women were locked out.”

A VISIT TO EVICTION COURT

A middle-aged woman in jeans and a striped knit shirt stands in court one August morning, asking the magistrate to evict her ex-boyfriend, who she says is physically and mentally abusive but won’t leave. But the law lets only landlords, not tenants, evict people. And the ex-boyfriend isn’t even on the lease.

In North Carolina, domestic violence is one factor that can, in some cases, prevent a tenant from being evicted. But this woman isn’t facing eviction. The magistrate asks about domestic violence restraining orders. The woman hasn’t been able to get one. The woman starts crying. “I don’t have any way to get this man out of my house. He’s beating me and my children. It seems like I have no recourse.”

The magistrate asks whether she has asked the landlord to evict the man. “My landlord says it’s not his business.” The woman says she’s afraid the landlord will instead, evict her and her five children.

But the magistrate can’t legally do anything and says, “I’m sorry.”

[highlight]Of about 30,000 evictions cases filed each year in Mecklenburg County, Legal Aid lawyers will represent about 1 percent – and win 95 percent of those.[/highlight]

In small claims court tenants rarely have lawyers. Rental companies are more likely to. It’s common for tenants not even to show up. On two different mornings, slightly more than half the people whose names were listed on daily dockets didn’t answer when the magistrate called them. If the plaintiff (landlord) isn’t there, the case is dismissed. If tenants aren’t there or don’t hear when the magistrate calls their name, the magistrate will usually enter an eviction judgment against them.

“The first time many people learn a judgment has been entered against them is when they get a note from the sheriff,” says Ted Fillette, senior managing attorney for the Charlotte office of Legal Aid of North Carolina. Legal Aid provides most of whatever legal representation tenants in the state get.

Eviction court is in small claims court. The case files don’t contain evidence, just the landlord’s complaint and other court papers. (Names blurred out here.) Photo: Mary Newsom

Eviction court is in small claims court. The case files don’t contain evidence, just the landlord’s complaint and other court papers. (Names blurred out here.) Photo: Mary Newsom

Eviction cases typically take place five days a week in three Mecklenburg courtrooms at once, with magistrates scheduled to hear an estimated 30 to 120 cases an hour. “What does it take to assume you only need 30 seconds or 60 seconds per case?” Fillette questions. “The presumption is people will not know their rights, can’t find the courthouse, or won’t have a defense.”

Of the roughly 30,000 Mecklenburg eviction cases filed in a typical year, Fillette estimates his office will represent about 350 to 400 – roughly 1 percent – “and we will win 95 percent of those cases.”

My two random mornings in eviction court illustrate magistrates’ different styles. One – who could not evict the abusive ex-boyfriend – carefully explains to tenants and landlords what she is doing and why and explains where in the courthouse to file an appeal, how long the process takes, what the law says, etc.

Dealing with a landlord who isn’t sure if he has a written or oral lease, she tells him: “If you have a written lease you have to have it in here with you if you’re evicting someone.”

But sometimes how the law gets applied depends on who the judge is. Another magistrate, on another day, is not as clear in explaining her actions. In one case she asks an apartment manager if he has the lease with him. He doesn’t. Despite the lack of that important piece of evidence, she orders the tenant evicted anyway.

THE LANDLORDS’ VIEW

Of course, many tenants cause huge headaches for landlords. Tenants damage things. They commit crimes. They create nuisances. They don’t pay rent. And bad tenants and evictees come from all economic backgrounds. Landlords can tell plenty of stories.

Scott Wilkerson has been in apartment management most of his adult life. His company, Ginkgo Residential, owns or manages about 6,000 units in three states, including about 1,500 in Mecklenburg. It focuses on the middle-price market, like the place we’re meeting, Parkwood Apartments off Independence Boulevard. Built in the 1980s, its rents average about $750.

Property manager Kent Adkins says Parkwood, which has 128 apartments, files about three eviction complaints a month, usually for nonpayment. But, he says, “If we’ve filed on the 15th and they come in on the 20th (and pay), we take it.” Only about once every other month, he estimates, does a case end with the tenant leaving.

Wilkerson and Adkins describe the process for renting to a new tenant. Like most landlords they use a third-party business for screening. They do a credit check. They require rental references for the past two years and want to see the two most recent pay stubs or a job-offer letter. They look at criminal history and court records. That’s where a court filing for eviction shows up even if the tenant eventually paid and was not evicted. For instance, before Candace was evicted, she says, she had found an apartment she could afford and was pre-approved.. But the landlord saw that twice in 2016 she was late with rent and eviction complaints were filed. Although Candace paid the rent and stayed, that record was enough to keep her out of the other apartment, and to make her – at least temporarily – homeless.

[highlight]“We have a major housing problem in this country. And we don’t have an answer for it.” — Scott Wilkerson, Ginkgo Residential, an apartment management company[/highlight]

Ken Szymanski, CEO of the Greater Charlotte Apartment Association, says that some months ago his group confidentially polled some members asking about their practice in renting to people who’d been previously evicted. “Every company has a different approach,” he says.

But, says Wilkerson, a felony – like the 1990s drug conviction of the man at Crisis Assistance – would likely disqualify a tenant.

Wilkerson recognizes the problem of ever-higher housing costs. He believes the private sector alone can’t solve it. He has run some numbers that show, as he puts it, “If the land and the buildings were free it would cost me about $500 a month to operate and maintain the typical 30-year-old apartment.” That includes staff, taxes, insurance, upkeep, etc.

“Matthew Desmond is absolutely right,” he says. “We have a major housing problem in this country. And we don’t have an answer for it. … There is no silver bullet.”

WITH THE DEPUTIES

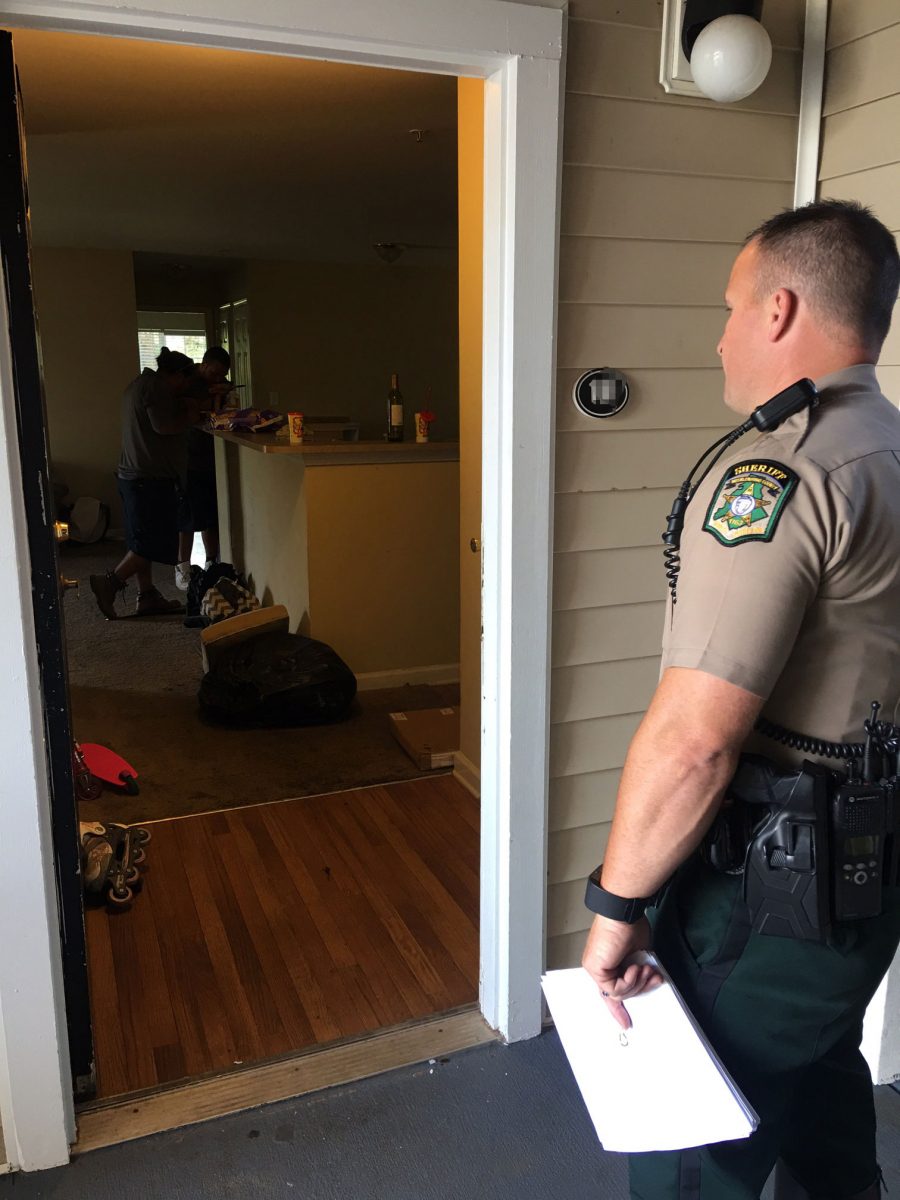

Mecklenburg sheriff’s deputy Mitch Adams starts his day with a list of six apartments to padlock. The sheriff’s department has allowed me to ride along and observe.

At the first place, as he drives into an apartment complex off Arrowood Road, a woman emerges from the office, saying, “She just paid,” and hands him a paper. Eviction averted.

Next stop: A large new complex in Ballantyne in south Charlotte. Adams checks in at the office, then heads to a building to wait for a maintenance worker. Technically, it’s the landlord – or more likely a manager or maintenance staff – who “padlocks,” which often means changing the lock. The deputy knocks to see if anyone is home, checks to be sure the place is empty, hangs the yellow cardboard eviction notice, and files the record stating that the padlocking took place.

MItch Abrams, a Mecklenburg County sheriff’s deputy, watches while the locks are changed at an apartment where the tenant couldn’t afford rent. Photo: Mary Newsom

MItch Abrams, a Mecklenburg County sheriff’s deputy, watches while the locks are changed at an apartment where the tenant couldn’t afford rent. Photo: Mary Newsom

Here, the tenant is gone. The $1,200-a-month apartment holds little more than a worn sofa, some rental furniture and an impressively stocked refrigerator holding, among other things, coconut cream pie, sweet potato pie and Häagen Dazs butter pecan ice cream.

Legally, the landlord can’t move the possessions for five to seven days and must allow the tenant access to them. Maintenance supervisor Nathan Sedlak says he’d rather let people get their stuff. It’s easier than having to call someone to haul it away.

Adams has done this job for the sheriff’s department about 12 years. He estimates tenants are home about 60 percent of the time when he arrives. He sees tough situations routinely. “When I started doing it, I had a young family,” Adams recalls. “I was heartbroken.”

Adams’ office, based at the Mecklenburg ABC Board on North Tryon Street, is the only one serving evictions. He says the five deputies average 15 to 70 notices a day.

Another deputy in the unit, Ryan Moore, says later that while he likes being on a motorcycle (the eviction deputies typically ride motorcycles) he doesn’t like doing evictions. In law enforcement, he says, you’re taught never to search a building by yourself. “But we do that every day.”

Sometimes they get called names. Sometimes there’s a mom with crying children. “To the 4-year-old or 8-year-old or 12-year-old,” Moore says, “then I’m the bad guy.”

ONE WOMAN’S STORY

The only tenant Mitch Adams encounters this morning is when Candace drives up as he is about to drive away. She tells her story a few days later, hoping maybe it can help someone else.

Like many evictees, Candace is black and a single mother. Her five kids range from 1 to 17. She has an open, friendly face and wears glasses. She speaks forthrightly, generally optimistically, about what she’s doing to improve her situation.

Sheriff’s deputies hang a yellow placard on the door of apartments where tenants have been evicted. Photo: Mary Newsom

Sheriff’s deputies hang a yellow placard on the door of apartments where tenants have been evicted. Photo: Mary Newsom

Two years ago, she decided to divorce her husband, who she says struggled for years with addiction and could be abusive. A year later, the divorce final, she found herself with a newborn, single and overwhelmed. “It was too much,” she says. She describes a downward spiral. Struggling with depression, she says, she left a $40,000-a-year job where she helped people apply for food stamps and Medicaid. But she couldn’t find another full-time permanent job, she says. With a high school diploma but no college degree, she began working temporary jobs at staffing agencies, earning at most $14 an hour. Now she’s permanent part-time at an assisted living center, but making only $10.50.

By early 2017, she says, “I got to the point where I realized, I wasn’t going to be able to stay here. I knew I couldn’t afford it.” She started trying to make arrangements ahead of time.

Like many people living paycheck to paycheck, she used her tax refund to pay the rent for several months. She sought support from various agencies. “I was trying to be proactive,” she says. She enrolled in the WIOA job training program created after the 2014 federal Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act. She gets food stamps, and the kids get Medicaid. She contacted the Salvation Army Center of Hope shelter but was told, she says, she had to wait until she was to be padlocked.

For many people without their own place, a car or van becomes a storage unit. Candace’s van is filled with belongings while she lives with a sister. Photo: Nancy Pierce

For many people without their own place, a car or van becomes a storage unit. Candace’s van is filled with belongings while she lives with a sister. Photo: Nancy Pierce

Deronda Metz, director of social services at the Center of Hope, confirms Candace’s description of the requirements. “You have to be literally homeless,” Metz says. “If she has a place to stay, she is not homeless.” The shelter has 360 beds and can serve about 400 a night. “But we’re full,” she says. “We’re full every day.” Her shelter is seeing an increase in families showing up who’ve been evicted. With limited funding, Crisis Assistance also must prioritize people facing the immediate prospect of having no home.

Candace is training to get certification for health care work. She focuses on the need to finish the training; when she was younger she started and then quit college a number of times. She tries to make things as stable as possible for her kids. The younger ones have scholarships for a private school run through her church and don’t have to change schools. She enrolled her two sons in Big Brothers Big Sisters.

The only time her composure falters is when she’s asked whether she regrets what’s happened. Tears well. “I’m severely disappointed. Because none of the kids asked to be here. They didn’t ask to be in this situation. I’m happy I left. I’m happy my kids see my strength. But it’s disappointing.”

She is not happy that agencies forced her to wait until eviction was upon her. “When I tried to be proactive, I felt like, ‘Oh no, these people won’t help me unless I stay to the very end.’ I had to wait until the sheriff came and put a sign on the door.”

Candace’s experience “is an amazing demonstration” of a problem with the current system, says Hardison, CEO of Crisis Assistance. Her agency’s mission, of course, is to help people in crisis. But in the larger sense, she asks, “Why do you have to be at the very end of the financial tumble? … There’s no nonprofit agency when the spiral downhill starts.”

She sees a larger societal problem. “The appetite for prevention simply does not exist,” she says. “How do you instill the understanding that prevention is more humane and more cost-effective?”

Candace’s story remains unfinished. So are the others I met. The man with who visited Crisis Assistance in August was still in his apartment in mid-September. He had gone to DSS and had been able to pay the August rent, and September. He was still at the out-of-town job training.

No one systematically tracks where people go when they’re evicted. A check in September of three of the eviction cases I saw in court in July found one empty home but at two others, the evicted tenants had been able to stay after all.

Staff at Crisis Assistance Ministry record clients’ information into their computer system. Photo: Nancy Pierce

Staff at Crisis Assistance Ministry record clients’ information into their computer system. Photo: Nancy Pierce

‘I’D RATHER SLEEP IN MY TRUCK’

At Crisis Assistance that August morning, another client has agreed to let me observe. He is rail thin and holds an envelope full of papers. His demeanor is a mix of anger, distrust and despair.

He is formerly homeless, he says. His case is complicated and hard to follow. But he is to be padlocked the following day.

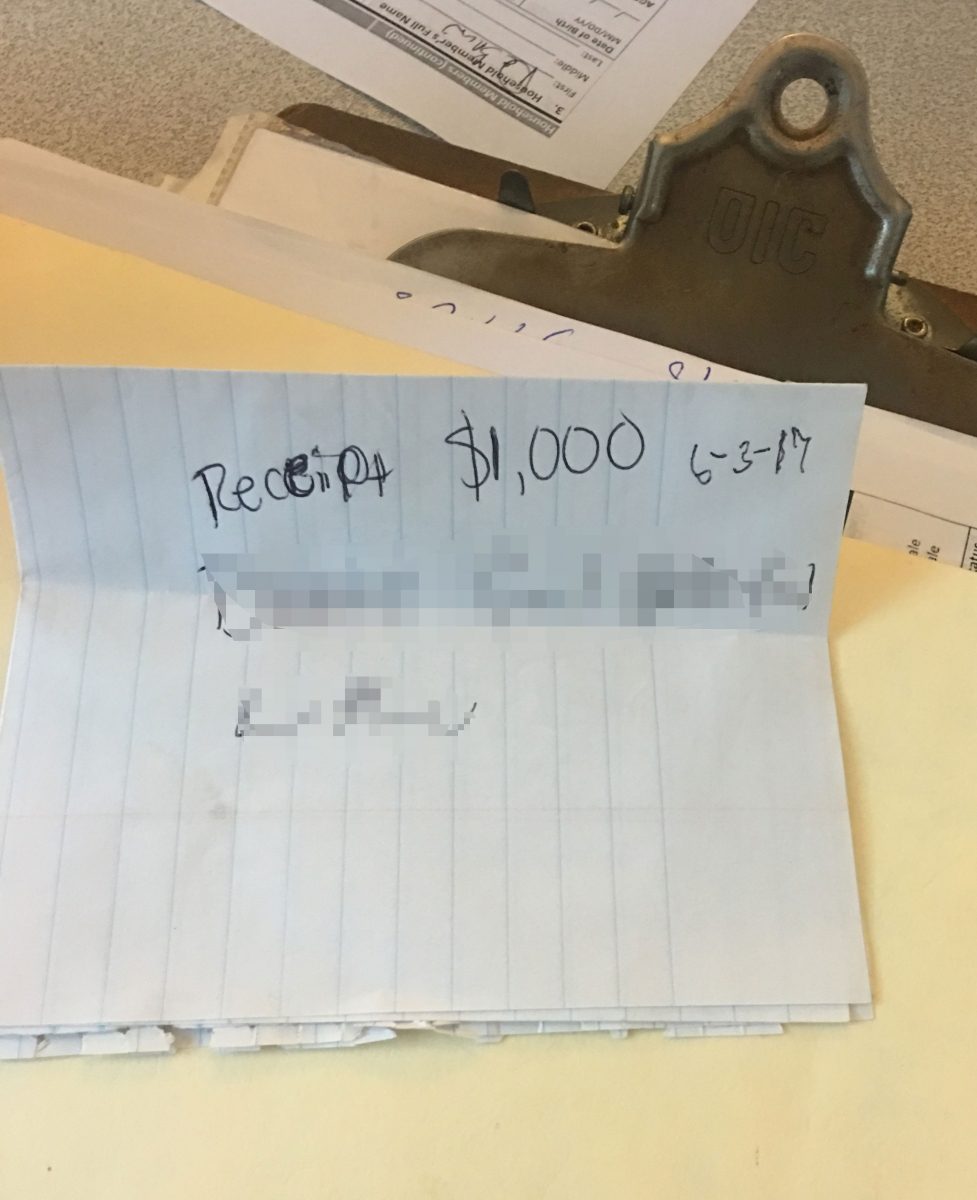

The receipt (with names deliberately blurred) shows the informal nature of some landlord-tenant relationships. Photo: Mary Newsom

The receipt (with names deliberately blurred) shows the informal nature of some landlord-tenant relationships. Photo: Mary Newsom

“I have no income,” he tells caseworker Rochelle McCrimmon, though later he says he gets food stamps and two of his children, who stay with him, get child support and disability.

His rent is $795. He complains that the house needs multiple repairs. “I have mold problems,” he says. “The stove doesn’t work. The fridge doesn’t work.” His water bill is $230, he says. “The whole sink is basically corroded.” McCrimmon asks if he has been to Legal Aid. If housing is unsafe a magistrate can order a rent abatement. He refuses her suggestion.

McCrimmon asks how much the landlord wants. He says he doesn’t know. He has a receipt showing he paid $1,000 in June. The receipt is a scribbled name and date on some folded notebook paper. The caseworker phones the landlord, who verges on incoherent. He says the man owes $4,000 but $2,000 would stop the eviction. The man says he has $1,000. But the caseworker can give him only $600.

A silent pause. “I’d rather sleep in my truck than go to any of the shelters,” he says.

She refers him to the only other place in the city that might be able to help him, the Good Friends fund, and offers bus passes. She urges him to look elsewhere for resources and call her back. It isn’t clear if he will do those things.

His face is tired. He rubs his eyes. “Have you eaten today?” McCrimmon asks.

“No,” he says. “I don’t want to eat.”

He stands up, and he walks out.