2015 explorer finds different Charlotte than Lawson’s 1701 journey

At least when explorer John Lawson came through here in 1701 it was winter.

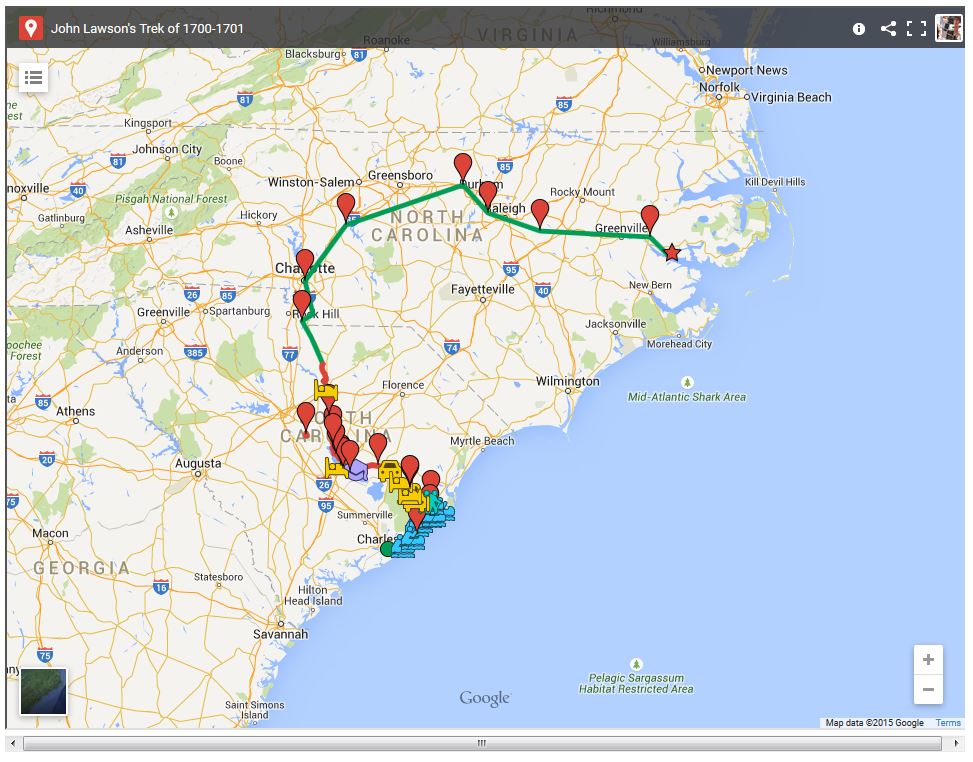

Scott Huler, a Raleigh-based writer, is retracing Lawson’s route from Charleston, S.C., to Pamlico Sound, N.C., and Tuesday he hiked from Charlotte to Concord.

When I picked Huler up for a midafternoon break, he had walked up North Tryon Street from The Square at Tryon and Trade streets and was in the bowling alley parking lot just past Orr Road. His plan: walk to the Charlotte Motor Speedway to camp, then Wednesday hike to Kannapolis.

My car thermometer registered 100 degrees outside. Construction for the light-rail line had torn up much of the street, and Huler was surrounded by hot new asphalt, pot-holed old asphalt, red clay dust, heavy equipment spewing fumes, a line of cars and no shade trees. “The idea,” he told a reporter last fall, “is to encounter the terrain with something like fresh eyes.”

Indeed.

We 20th- and 21st-century Charlotteans and Carolinians may marvel at changes we’ve seen in recent years, as growth alters local landscapes in some cases beyond recognition. But if Lawson could see what the old Indian Trading Path (now North Tryon) has become – mobile home parks, used tire stores, fast-food joints and asphalt parking lots everywhere – he might think he’d gone to hell.

We 20th- and 21st-century Charlotteans and Carolinians may marvel at changes we’ve seen in recent years, as growth alters local landscapes in some cases beyond recognition. But if Lawson could see what the old Indian Trading Path (now North Tryon) has become – mobile home parks, used tire stores, fast-food joints and asphalt parking lots everywhere – he might think he’d gone to hell.

Or maybe not. Lawson was deeply interested in observing what he found on his 550-mile trip, and he might well have been just as fascinated with today’s streets and highways. One reason his A New Voyage to Carolina about his 1700-01 journey has fascinated Carolinas readers since its 1709 publication is its careful descriptions of the land, animals and plants he found decades before European settlers arrived to plow the soil for crops and build houses and villages.

As Huler took a break in the air-conditioned Amelie’s coffee shop on North Davidson Street, he recounted getting the idea for the trip and the book he’s writing. He was trying to research the land use history of his house in Raleigh’s Five Points neighborhood. To learn about the pre-Colonial era, he read Lawson’s account. Then he sought more recent books examining where Lawson had gone. There weren’t any.

And so began his Lawson Trek. Huler’s keeping an online journal at Lawsontrek.com. He started in Charleston in October. “The first thing I learned– without a doubt – is that Lawson never paddled his canoe,” Huler told me. “Because I found, after three hours in a canoe in the Intracoastal Waterway, in those marshy, tidal creeks, you’re interested in only two things in your entire life – which way is the current running? Which way is the wind blowing? That’s all you care about.”

Among those helping Huler along his way have been independent Lawson researcher Val Green from Fairfield County, S.C., barbecue expert Dan “Dan The Pig Man” Huntley in York County and Charlotte-area GIS specialist and living-history surveyor Dale Loberger, who seeks out old roads.

More about John Lawson

|

After his canoe escapades, Huler went up the Santee River, toward the Wateree River. Some of his most memorable experiences: “We had cake and coffee with descendants of the Huguenots with whom Lawson would have hung out. How crazy is that? The next trek after that, I hung around with the vice chief of the Santee Indians in South Carolina, who was a descendant of the Santees who treated Lawson so well.”

Huler is not through-hiking. He walks and camps for several days for the trek, then resumes his 21st-century life. He drove from Raleigh Tuesday morning, dropped camping gear at Charlotte Motor Speedway, drove to Kannapolis and left his car there, getting a ride into Charlotte with Charlotte Magazine editor Michael Graff.

One continuing thread of his journey has been the difficulty of walking through both rural areas and cities. “The best surprise I had in Charlotte was the sidewalks,” he wrote in a piece published June 12. “Throughout my walk I have complained, pretty much constantly, about the lack of sidewalks and capacity for pedestrians to share the roads. Some of that comes simply from walking through very rural territory. But the approach to every city has meant running for my life, and approaching Charlotte from Pineville, where I stopped last time, was no different.

“Pineville is a little comfortable suburb, with streets and sidewalks and shops, and then you run out of sidewalk and you cross I-485 and you just pray that you stay lucky. And then you walk along a strip of soul-sucking highway with about 16,741 car dealerships (that’s an estimate; I might have missed a couple.)

“But then an astonishing thing happens. You find yourself on South Boulevard and … there’s sidewalk. And I’m here to tell you, that for the ten-or-so miles it takes you to get into Charlotte, you have sidewalk the whole way, and for that I could just weep with gratitude.”

Huler and other Lawson experts believe the explorer stayed several days in Charlotte at what is now the middle of uptown, where two Indian paths intersected. Lawson describes his journey after crossing what was likely the Catawba River: “We pass’d over an exceeding rich Tract of Land, affording Plenty of great free Stones, and marble Rocks, and abounding in many pleasant and delightsome Rivulets.”

That night Lawson’s party stayed in one of the Indian towns, where he wrote, “There ran, hard-by this Town, a pleasant River, not very large, but, as the Indians told us, well stor’d with Fish.”

Lawson’s book describes his stay in the “Kadapau [Catawba] King’s House.” Then he made his way northwest, lodging “by a Hill-side, that was one entire Rock, out of which gush’d out pleasant Fountains of well-tasted Water.”

I dropped Huler off to resume his scorching trek up North Tryon Street. At least there was a sidewalk on one side. He arrived at the speedway a few hours later, pitched his tent, and on Wednesday had made it to Kannapolis before noon. “Done hiking for the day,” he emailed me. And as any good explorer would, he knew there was more to see, adding: “Going to the Earnhardt statue now.”

Opinions in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.