Will Americans continue to be suburban creatures?

Will Americans continue to be suburban creatures?

The question has been widely debated by developers, planners and the press since the Great Recession. Surveys showing preferences for urban, walkable, in-town neighborhoods have been called fads by some, or hailed by others as the end of suburbia. Ultimately, it will be the attitudes of the Millennial generation that will shape the future urban landscape.

The debate was triggered by the recent flurry of new multifamily, urban residential projects in nearly every mid-sized city in the country. Local examples include Charlotte’s South End and Plaza-Midwood areas. Some observers call this shift a fad and predict most of the young urbanites will return to the suburbs once they begin to have children. Unfortunately, since there is little data (pro or con) to support predictions of urban change, today’s debate relies on anecdote and assumption. This generally devolves into a declaration of absolutes (e.g. “death of the suburbs”). In reality, changes in urban form are incremental rather than absolute.

One example of the extremist approach to debating the future of our cities can be found in the interpretation of the 2011 Survey of Community Preferences by the National Association of Realtors (NAR). The survey was widely trumpeted by the press (and the NAR) as evidence that Americans strongly preferred Smart Growth (in-town, walkable areas) to single-family subdivisions (click here for more information).

While the survey does, in fact, show that most Americans desire homes in walkable, mixed-use communities with access to transit, the survey also finds Americans express a strong preference for communities that offer privacy, highway access and single-family housing. A close reading of its findings reveals the complex (and often contradictory) image that Americans have of their residential ideal. The NAR survey indicates that traditional suburbs have lost their luster for many, but urban high-rise living should not be considered the preferred alternative.

The ambiguity of the 2011 NAR survey was compounded by problems with its survey sample — it focused on middle-aged homeowners, a group with large, fixed investments in (mostly) suburban housing, making them less mobile than other demographics. In order to collect opinion data from a group who will be making new residential choices within the next three years, I conducted a survey of 672 college students during fall 2012. The subjects attended Sun Belt universities with either suburban campuses (UNC Charlotte and Sam Houston State University) or small-town campuses (James Madison University and the University of Oklahoma). While the sample is ideal in one sense (this group is the core of the Millennial cohort which makes up nearly one quarter of the U.S. population), it is problematic in others (only a small portion of this group has dealt with the financial realities of adulthood and family life). Portions of this online survey were designed to use the 2011 NAR survey as a baseline to gauge generational shifts in housing demand.

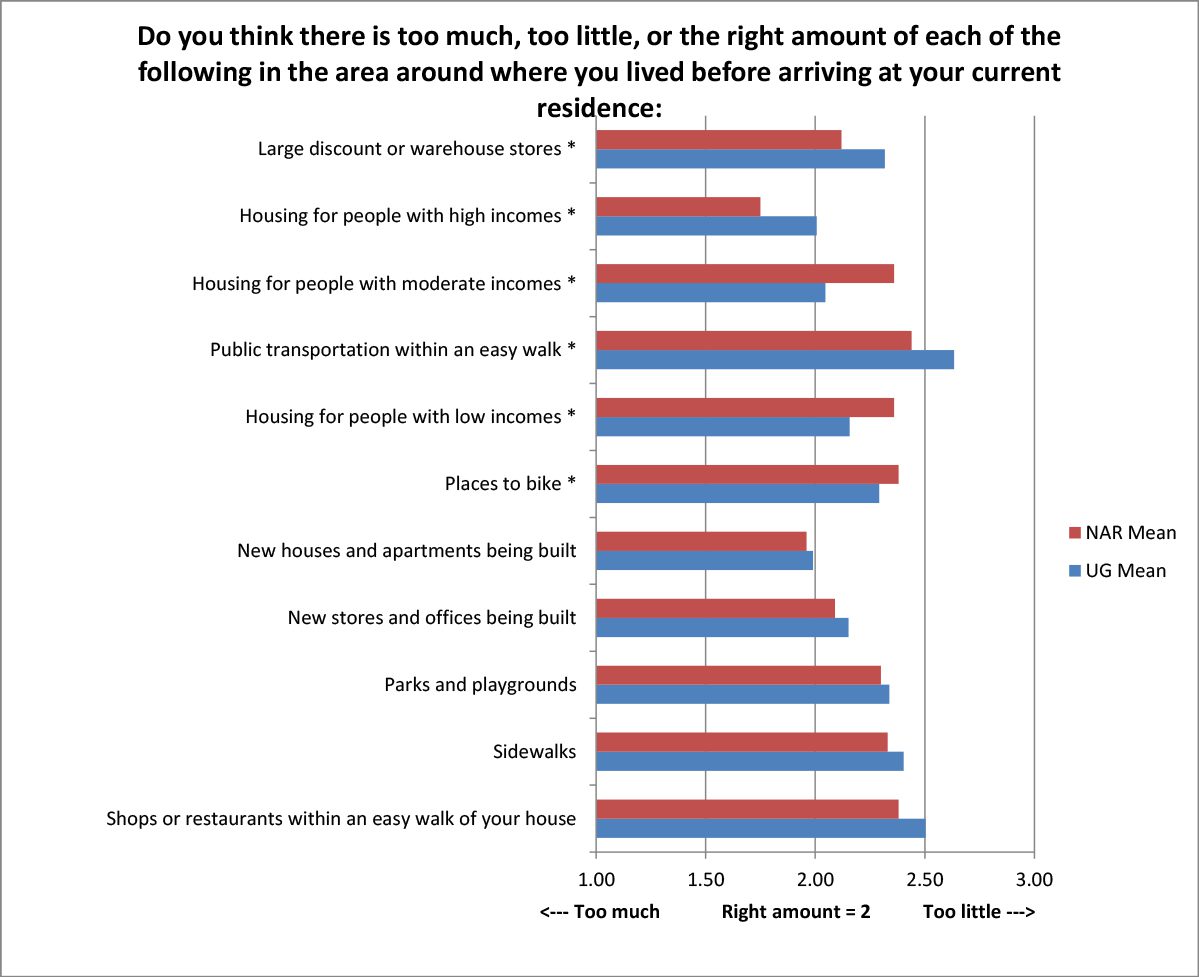

In general terms, the college students expressed residential preferences similar to the opinions of the older NAR sample. While much of the conflicted ambiguity of the NAR survey is expressed by the Millennials, they do express a significantly stronger preference for access to transit than the older NAR respondents (average of 2.63 by undergraduates, compared to average of 2.44 by NAR group, on a scale of 1 to 3). The charts below show the responses of undergraduates in blue and the NAR respondents in red.

Sources: National Association of Realtors; survey of undergraduates by author.

* Indicates that means are significantly different.

NAR =National Association of Realtors, UG=Undergraduate student survey

Note: Values range from 1 (too much) to 3 (too little).

When asked their opinions of the communities they lived in before arriving at college (or buying their current dwelling in the case of NAR respondents), the students placed greater value on proximity to big-box retailers (2.32 compared to 2.12 on a scale of 1 to 3 in chart above), accessibility to public transportation (2.63 compared to 2.44), and a lower value on the availability of “places to bike” than did NAR respondents (2.29 compared to 2.38) – although this amenity is still thought to be above average in importance. In addition, undergraduates expressed a clear bias against mixed-class neighborhoods (with an average of 2.05 compared to 2.36); they preferred an idyllic, high-income neighborhood over mixed-income housing (student survey average of 2.01 compared to the NAR average of 1.75).

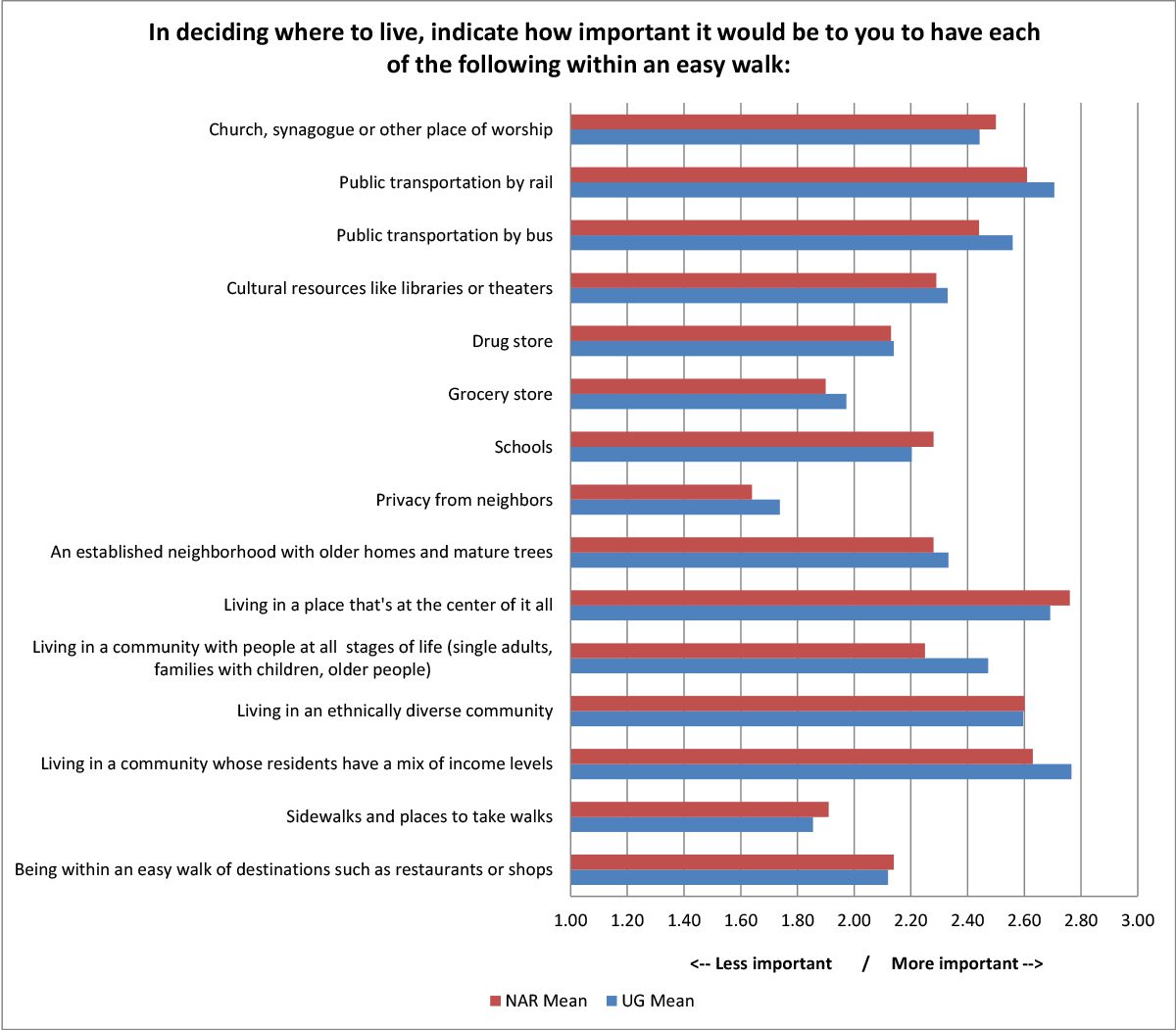

When asked about future residential choices (chart below) there were few significant differences in the undergraduate students and NAR respondents. Future home-buyers desire walkability to public transportation and activities (vaguely defined), but place less importance on walkability to drug and grocery stores. Both groups indicated that privacy and the availability of “places to take walks” were the least important element of residential choice.

Sources: National Association of Realtors; survey of undergraduates by author.

Note: Values on the chart range from 1 (not at all important) to a maximum of 3 (extremely important).

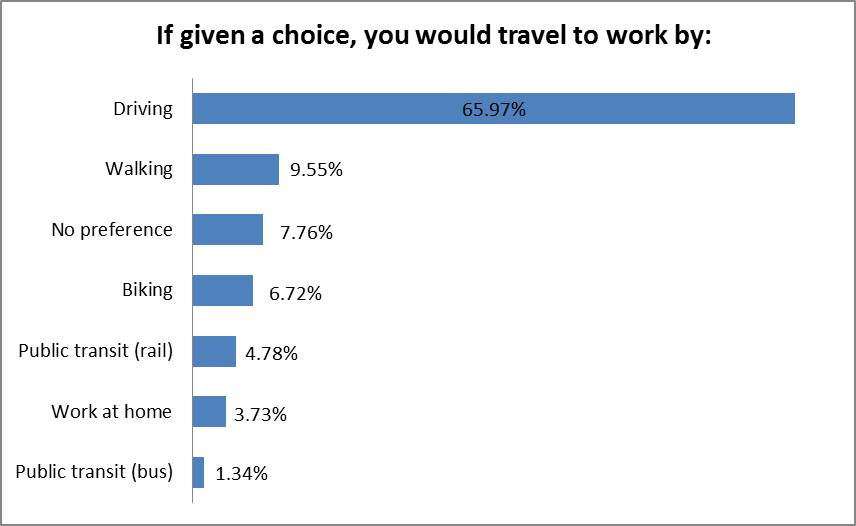

The sharpest contrast between the preferences of the Millennials and the current urban landscape is their preferred mode of transportation to work. While two-thirds of Millennial respondents preferred to drive to work (chart below), 86 percent of Americans currently drive to work, according to Census estimates. More remarkable is that nearly a quarter of Millennial respondents prefer transit, biking or walking – a number three times the current average. The desire of this generation to reduce their reliance on the car is consistent with other recent surveys. These data do suggest that cities that provide non-auto transportation options will have an advantage in recruiting this demographic.

Source: Survey of undergraduates by author.

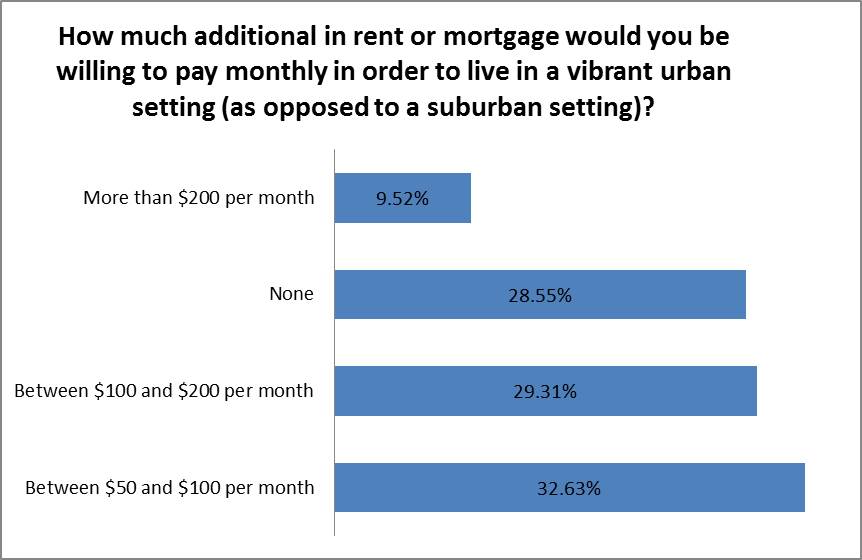

Most residential choice is driven by cost. Suburban growth was driven, in part, by inexpensive housing. The undergraduate survey asked what price they would be willing to pay to live in a vibrant, urban setting (described as high-density housing with multiple activities within walking distance) instead of a traditional suburban environment (described as single-family housing in single-use neighborhoods). The NAR survey did not ask this question. Nearly three quarters of respondents desired a more urban environment enough to pay $50 per month premium (or more). While the specific characteristics of the urban environment were not detailed in the survey question, it does appear a significant majority of Millennials are willing to pay a premium to live a less suburban lifestyle.

Source: Survey of undergraduates by author.

While these survey data suggest that much of the Millennial generation will seek more urban residential settings in their first home, few 20-year-olds are able to predict how their preferences will change at middle age. The ability of developers and planners to affordably provide communities that appeal to this generation as their needs shift (while simultaneously accommodating the aging urban baby-boomers) will determine the future of the city.