Gastonia, New York, Jane Jacobs and me

New York City and Gastonia don’t, at first glance, appear to have much in common. Yet both Manhattan and the much smaller city in the Piedmont of North Carolina can offer an example of “urbanism.” And both have suffered grave harm from well-intentioned “progress.”

Charlotte architect Terry Shook, speaking last month at the showing of a documentary film about urban writer Jane Jacobs, reminisced about growing up in Gastonia, about his first visit to New York City, and about how he came to understand and appreciate his much smaller Southern hometown.

Jacobs, in her 1961 book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, described the rich fabric of neighborhood life in New York’s Greenwich Village: the small interactions between neighbors and the role of small businesses and even the street “characters” in making sidewalks safe and keeping the city vital.

And it’s not just in New York, Shook warned, that so-called civic improvements, such as the freeways through Manhattan that Jacobs fought, can have unintended ill effects.

The film, Urban Goddess: Jane Jacobs Reconsidered, described Jacobs’ fights against a proposed freeway through lower Manhattan and recounted her reflections, showing how they apply today in Brooklyn, Toronto, Vancouver and other cities. The film showing was part of the Bechtler Museum of Modern Art’s Art + Architecture program, sponsored by HDR in partnership with AIA Charlotte.

Shook’s remarks, edited for clarity:

In 1977 I had the pleasure of visiting New York for the first time.

I was a freshly minted architectural undergraduate from UNC Charlotte. A fellow classmate Graham Adams and I, along with a zany fellow who had been a professor at N.C. State, decided on a whim that we would go to New York City.

So I woke up early one Saturday morning, sleeping in the back seat of this impossibly small Toyota, in Brooklyn, on one of the great townhouse streets in all of America. Coming from Gastonia, of course, I had never seen a proper townhouse. It was near a park, and the street was already bustling, early in the morning, with all kinds of people.

During the next 48 hours we took in everything there was to take in in New York City – from Chinatown to Spanish Harlem, eating in Cuban-Chinese restaurants, to the West Village, which Jane Jacobs so incredibly loved. For me, this child who grew up in a small town in North Carolina, to be there in New York and see a big city, full-blown, with all the humanity on full display, in the streets and the neighborhoods, was beyond intoxicating.

All those sentences that I had read in Jane Jacobs’ classic book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities – when in the midst of this place, you understand it. It becomes a part of who you are.

You see the incursions of the freeways in New York, and you understand the holy battle she waged to show how these rational, well-explained propositions supported by generally well-meaning people were so misguided.

I’m sure everyone in this room has read her books, but you cannot understand Jane Jacobs unless you also read Robert Caro’s 1974 biography of Robert Moses, [The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York.]

I was in graduate school at N.C. State at the time, and as I came back, my head buzzing from New York City, from this experience, I reflected on the city I grew up in, Gastonia.

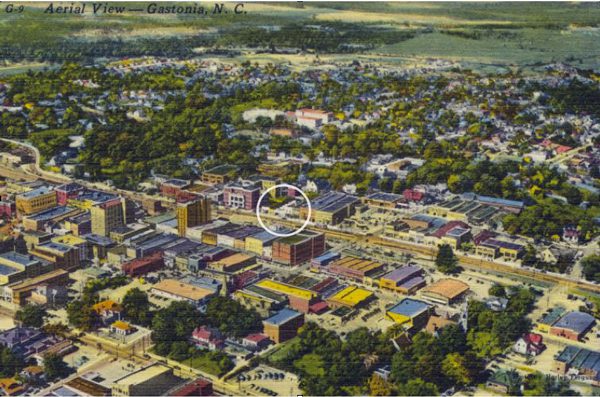

My dad’s construction business was in downtown Gastonia. The railroad tracks ran right through the middle of town. A wonderful passenger depot was still there at the time, a Richardsonian-inspired depot, cobblestones still all around the station. There was an equally great freight terminal, and there was a seamless link between this stream of commerce, where my dad had his business, and Main Street of downtown Gastonia. It was very much alive.

I reflected on the life I had had there as I grew up in that small town. In my own way, I was exposed to characters and personalities, to a network like the one Jacobs described in New York, a network of people who in almost an unspoken and undefined way, took care of the environment of which they were a part, and of the relationships they formed along the way.

What made it equally poignant for me was that during the same time I was in school, other well-meaning people – not unlike those who proposed freeways inside New York City – had plotted a strategy to bury those railroad tracks. Right where my dad’s place was, all those buildings and houses were going to be wiped out, to create a depression into which one could put the trains.

Of course, that was an unstoppable force. It’s now there. [It opened in 1991.] Residents of Gastonia affectionately refer to it as “the ditch” – usually preceded by other descriptors that I will refrain from using.

At that time I thought about that proposal, and I wondered, “What would Jane Jacobs have done? This is no different from a freeway.”

None of the buildings on the street where my dad had his modest operation were of any great architectural consequence, but, along with the streets of which they were a part, they did form a fabric, a fabric which a city could grow and maintain – great threads that defined that place during that time.

But the opportunity to maintain it and grow is lost, and it’s still lost. And that poor town struggles because of that ditch and many other things that happened to it. The irony was that the railroad ditch was put in, in part – so a local story goes –because a department store wanted more spaces behind a building that they were about to abandon, because they were negotiating to go to the mall.

Well-meaning people do many things, but you have unintended consequences.

Jane Jacobs’ book and the city that was the focus of Jane Jacob’s love inspired me and had a profound impact on my career.

Let’s take inspiration from this movie and know that even in our time and place, while we have this great city in which we’ve all done things, it still needs a lot of care and nurturing. It still requires our vigilant efforts to fight back against good and well-intentioned ideas that can destroy that which makes us human – the spaces in which we live our lives.

Terry Shook, FAIA, is a founding partner of Shook Kelley, a firm specializing in strategic consulting services in disciplines of consumer psychographics and brand development along with specialties in urban planning, architecture and communication design, all focusing on how places and spaces convene humans in meaningful ways. He graduated cum laude in 1976 from the UNC Charlotte College of Architecture.

Views expressed in this commentary are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute, its staff, or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.