Officials: Charlotte can’t meet its bus system needs without more revenue

In Charlotte’s new transit and mobility plans, multibillion-dollar light rail lines tend to get most of the attention. But the delay in a planned 1-cent sales tax referendum is having a big effect on another, less flashy part of the system that actually carries many more riders: Buses.

The Charlotte Area Transit System has been trying to reverse falling bus ridership and lure riders back for years, in large part by making the bus system less hub-and-spoke centric through additional crosstown routes (the average trip that requires riders to come all the way to the transportation center uptown, switch buses and ride out again takes 90 minutes each way, CATS has said), “straightening” popular routes to make them faster, and increasing frequency (or “headways”) to every 15 minutes on high-ridership routes.

The ultimate goal, officials have long said, is a bus system with waits of no more than 15 minutes on all routes, and even less on the most popular. Many routes still see a bus only every 30 minutes or longer.

[Book Review: Can we fix our struggling bus systems]

But doing so would ultimately require CATS to buy a lot more buses and hire a lot more bus drivers – which would require a lot more funding. That idea got a dash of cold water thrown onto it this week at a City Council budget meeting.

In addition to an estimated additional $35 million in annual operating expenses, buying enough buses to cut all the city’s bus wait times would cost about $100 million. Without a new revenue source, CATS chief executive John Lewis said the best the system can do is keep “chipping around the edges.”

“In order to reach the overall stated goal of all of our routes being no more than 15 minutes, we will have to add more,” he said. “The current half-cent sales tax will not support that goal.”

That’s a disappointment to officials who have been pushing for more investment in the local system. Mayor Pro Tem Julie Eiselt had previously said she hoped 2020 would be the “year of the bus.”

“It looks to me like that’s not something we’re considering at this point,” she said this week. “Until we really get to a point where we can pass that transit tax…we can’t envision a transformative investment into our bus system.”

“That’s correct,” said Lewis.

The Backstory

Mecklenburg County’s half-cent sales tax, in place for more than two decades, is CATS’ biggest source of funding. Last year, it brought in $108 million. The voter-approved tax funds CATS’ operations and paid for the local share of the Blue Line and the Blue Line extension (with the state and federal government picking up about three-quarters of the overall construction cost).

But without a lot more money, CATS won’t be able to build the Silver Line east-west light rail, the Red Line to north Mecklenburg, other envisioned rail lines and extensions – or dramatically improve the bus system. That’s why the Charlotte Moves task force last year recommended the city pursue an additional 1-cent sales tax to fund at least half of the city’s estimated $8 billion to $12 billion transportation plan (with, again, state and federal funding accounting for the rest).

To put a new sales tax in place, Charlotte needs voter approval through a referendum. To get a referendum on the ballot, Charlotte needs permission from the state legislature and Mecklenburg County commissioners – both groups that expressed reservations about the prospects for a referendum this year. Ultimately, however, pandemic-related delays in Census data mean North Carolina is all but certain to delay municipal elections this year (because rebalancing districts isn’t possible), so a referendum is pretty much a moot point until 2022 anyway.

Buses carry most riders

In Charlotte, trains get the headlines but buses get the riders. The bus system remains the backbone of public transportation here, a trend that’s only been exemplified by the covid-19 pandemic. Local bus ridership is down 50% this fiscal year, while the Blue Line light rail has seen ridership plummet 72%.

So far this year, local buses have accounted for 3.3 million trips, while the light rail makes up 1.5 million.

The size of the necessary investment for a faster bus system seems small compared to the proposed light rail: $100 million or so in capital expenditures and $35 million in operating costs, compared to billions (including federal and state funds) for more trains. But rail lines are seen as providing a number of advantages buses don’t, such as faster, guaranteed travel times (since they don’t wait in traffic). Rail lines also kick off economic development booms (like along the Blue Line in South End and the Blue Line extension north to UNC Charlotte), which makes them attractive to local politicians.

Lewis said that CATS maintains about 20% spare, excess capacity in its bus fleet, so there’s still a bit of wiggle room to expand service and increase some frequencies.

“We have a bit of elasticity,” he said. “That gives us flexibility to add an incremental amount of frequency.”

But without a “transformational” investment, Lewis said, any upgrades will remain just that: incremental.

Regional picture

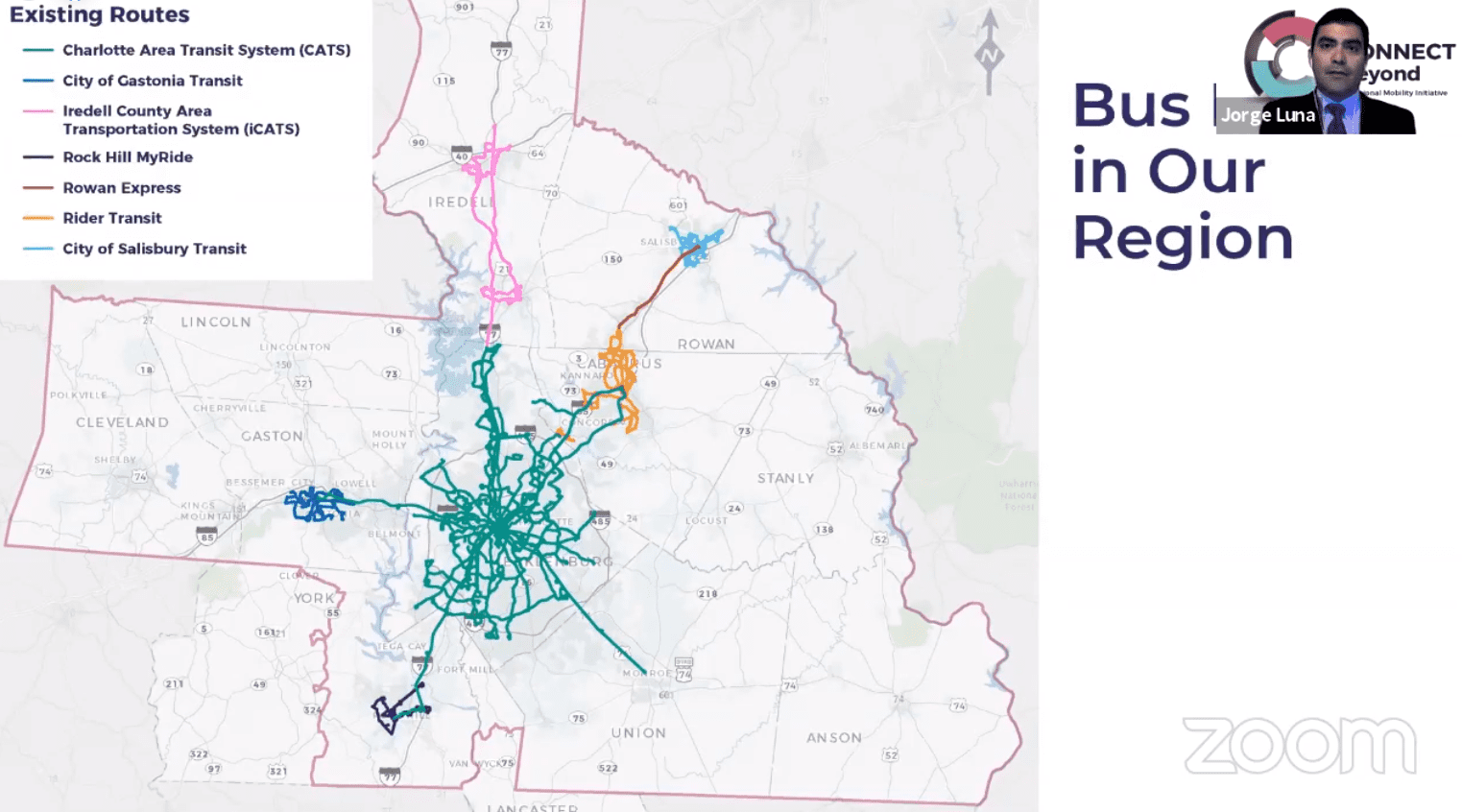

Bus routes in the Charlotte region. Centralina Regional Council

Discussions about upgrading Charlotte’s bus system come as there’s more focus on regional transportation planning than we’ve seen in a while. Led by CATS and the Centralina Regional Council, the Connect Beyond transportation initiative is starting to envision a regional bus system.

That would involve coordinating schedules, increasing frequency in other counties, aligning amenities and using a single fare system so riders could transfer seamlessly. In addition to CATS, six other local transit agencies (such as Gastonia Transit, Rider Transit of Concord and Kannapolis and My Ride Rock Hill) operate scheduled, fixed-route bus service.

Creating a regional bus system, however, would require more money – even more than meeting CATS’ stated 15-minute frequency goal. Charlotte Mayor Vi Lyles said that’s a challenge the region doesn’t yet have a clear path to overcome.

“This is just one of our real conundrums,” she said. “We see the vision, what possibilities there are… If we had resources, we’d do this so quickly.”