At 80, biologist Matthews still stalks the threatened landscapes

By Amber Veverka

Jim Matthews walks through the damp woods, and as he does, he pays no attention to the branches dripping with last night’s rain, the mucky path or the scolding of jays overhead. Those things don’t matter to Matthews. Not when he’s trying to explain the sex life of ferns.

“This is the sterile leaf and this is the fertile leaf,” he tells a visitor. “This is about to release its spores and they’re going all over the place. They’ll form gametophytes. The sperm swim in the water that’s in the soil to reach the eggs. They mature at different times so the plant doesn’t self-fertilize.”

Matthews’ impromptu biology lecture may be lost on his fellow hiker, but there’s no missing Matthews’ intense focus, his dedication to discovery. Matthews, a retired UNC Charlotte biology professor, is a botanist whose mission is to collect and catalog the plants of the 15-county region of the North Carolina Piedmont—preserving a record of what we have, before it’s lost.

The work is taking on new importance—and urgency—as the region explodes in growth. If current trends continue, by 2030, 97 percent of Mecklenburg County’s land will be developed, up from 71 percent today, according to research by the Mecklenburg County Park and Recreation Department and the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute.

The work is taking on new importance—and urgency—as the region explodes in growth. If current trends continue, by 2030, 97 percent of Mecklenburg County’s land will be developed, up from 71 percent today, according to research by the Mecklenburg County Park and Recreation Department and the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute.

And so, at age 80, Matthews keeps climbing ridges and descending ravines, gathering plants in places that are on their way to becoming parking lots.

A guardian of thousands of plant specimens

You can catch up with Matthews as he treks through the woods and fields with the agility of a much younger man, but he’s equally likely to be seated at a lab table inside the Dr. James F. Matthews Center for Biodiversity Studies—an office housed at the nature center at Reedy Creek Nature Preserve in northeast Mecklenburg County.

He’s a volunteer in this herbarium that bears his name, a collection whose foundation was preserved plant specimens for which UNC Charlotte and Davidson College no longer had room. Matthews, who earned his master’s degree at Cornell University and doctorate at Emory, gathered countless specimens himself during years of fieldwork with UNC Charlotte biology students. Now he works alongside herbarium curator Catherine Luckenbaugh.

Together they serve as guardians of some 45,000 species of plants gathered, pressed and methodically stored in gray metal cabinets in a climate-controlled space. Pictures are good, Matthews and other botanists agree. But the actual physical thing, the tendrils and roots and leaves and DNA—that’s far better.

Together they serve as guardians of some 45,000 species of plants gathered, pressed and methodically stored in gray metal cabinets in a climate-controlled space. Pictures are good, Matthews and other botanists agree. But the actual physical thing, the tendrils and roots and leaves and DNA—that’s far better.

The collection at Reedy Creek is no mere storehouse. It’s called upon regularly to answer questions from researchers across the continent, questions about species identification, ecosystem health and, now more than ever, climate change.

“That research is critical,” says Jim Garges, director of Mecklenburg County Park and Recreation. “You never know, through research, what you’re going to learn from a plant or animal.”

Not long ago, a university asked to borrow all of the herbarium’s flowering dogwood records, part of an investigation into whether the tree is flowering earlier due to a warming climate. Meanwhile, when they’re not collecting, Matthews and Luckenbaugh are busy uploading thousands of paper records online to make research easier—and investigating more than a few botanical puzzles of their own.

A storehouse of mysteries and lost species

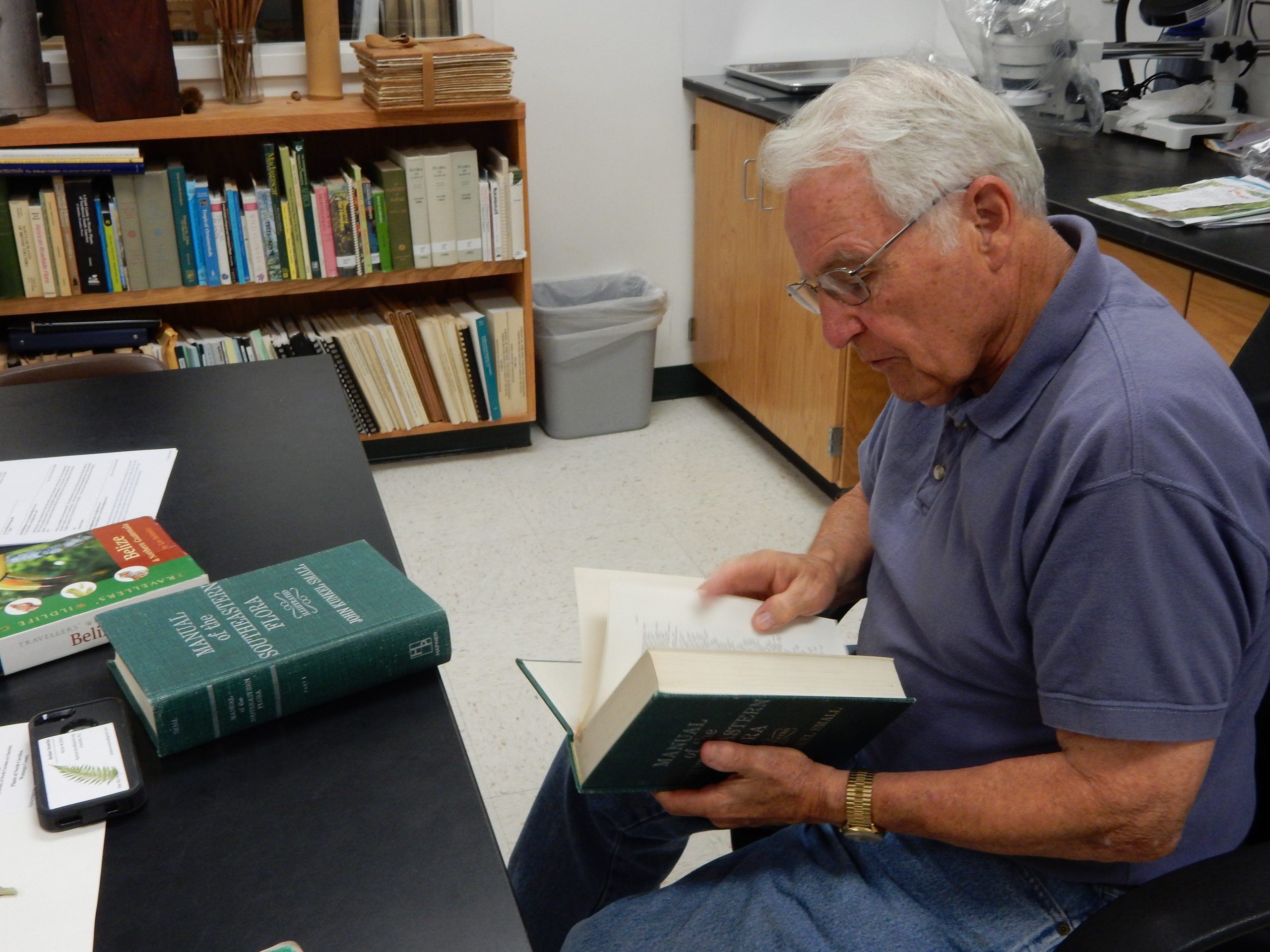

On one afternoon, a visitor to the herbarium finds Matthews poring over a weathered copy of the Manual of Vascular Flora of the Carolinas—a book, it’s worth noting, that credits Matthews in the acknowledgements—and studying a dusty plant specimen fixed to a large mounting sheet. He’s talking in the terse, professorial way that calls on a listener to figure out what he means without the benefit of a lot of extra explanation.

“It’s an enigma,” he says, of the specimen he’s studying. This faded green plant was picked in Polk County, in the southern N.C. foothills, back in 1897, but careful drying and preserving on special acid-free paper has preserved it intact. The plant is the “type” – the specimen that serves as the reference point for the species the first time it has been scientifically described in writing. A type is the particular example that scientists will return to again and again. Not only is this little plant the type for its species, “it’s the only specimen in existence,” Matthews says. “This is absolutely fantastic.”

He interrupts himself to take a phone call, which happens to be about the plant in question—a plant whose origins apparently have been in doubt. “All the data in the New York Botanical Garden database is wrong,” he excitedly tells the researcher on the other end of the line. “They’ve got it in Ohio and that’s wrong. On the back we have a letter from [Willard W.] Rowlee—nobody else has it … a letter dated 1899. It reads, ‘My Dear Dr. Small, I am sending you a today a specimen of Psoralea which I take to be a new species …’ ”

He interrupts himself to take a phone call, which happens to be about the plant in question—a plant whose origins apparently have been in doubt. “All the data in the New York Botanical Garden database is wrong,” he excitedly tells the researcher on the other end of the line. “They’ve got it in Ohio and that’s wrong. On the back we have a letter from [Willard W.] Rowlee—nobody else has it … a letter dated 1899. It reads, ‘My Dear Dr. Small, I am sending you a today a specimen of Psoralea which I take to be a new species …’ ”

After the phone conversation, Matthews gives a brief tour of the herbarium. He and Luckenbaugh are happy to show off plants now extinct in the region, such as a kind of galax once found in a tiny, northwest corner of Mecklenburg.

Once, but no more. “That site is now under Lake Norman,” said Luckenbaugh.

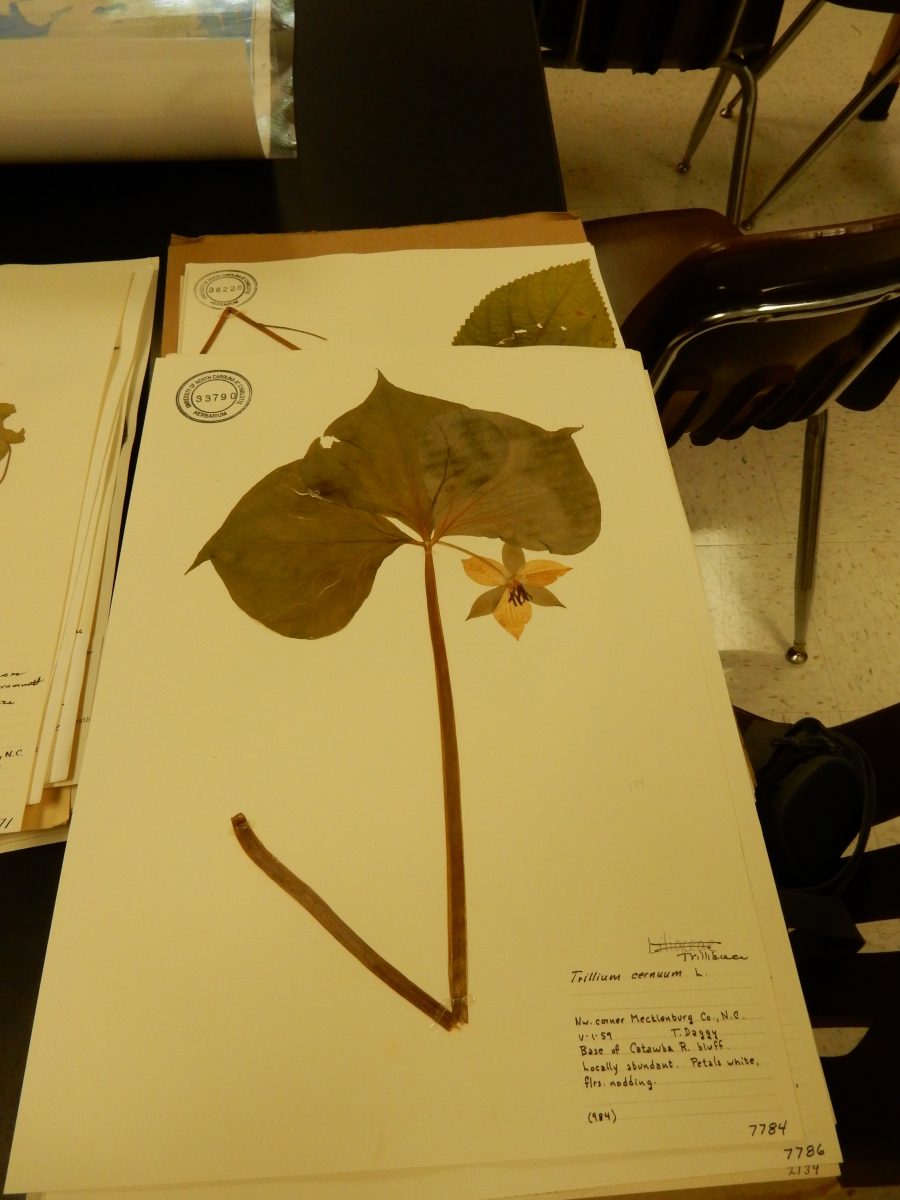

She then carefully lifts out of a cabinet a sheet with a specimen of trillium, the three-petaled beauty of springtime woodlands. “Trillium cernuum,” she says. “This would have been [at] the eastern edge of its range in Mecklenburg County. There’s greater genetic diversity in the edges of populations and now we’ve lost that edge.” Galax, for instance, “isn’t east of the Catawba River anymore,” she says.

He chronicled plants of the now-lost Piedmont landscape

This is where a visitor may start to wonder how Matthews can keep showing up for this work, haunted as he is by the ghosts of lost landscapes.

This is where a visitor may start to wonder how Matthews can keep showing up for this work, haunted as he is by the ghosts of lost landscapes.

Even just to ask him about discoveries he’s made is to get a brief tour of the Piedmont That Used To Be—the rare sunflowers obliterated by Northlake Mall, the secretive quillwort plowed under at Ballantyne, Mallard Creek’s magnificent chestnut oak forest, felled for offices.

Matthews speaks in straightforward terms about what motivates him. “I grew up on a dead-end street in Winston-Salem,” he says. “I was in the woods all my life. [This] is what I was destined to do.”

And while Matthews admires the heroes of the botanist’s faith—18th-century explorers such as John and William Bartram, Andre Michaux and Mark Catesby, who rambled the virgin forests of America and recorded a staggering wealth of plants—he doesn’t romanticize the past, before development wiped away so much.

“If I could change anything, I would,” he says. “But I’m a pragmatist.”

Matthews fought to preserve habitats

And yet, the very woods surrounding the Center for Biodiversity are evidence that Matthews has changed things. He helped convince the City of Charlotte to buy the Reedy Creek land before it fell to development, and it became a nature preserve in 1981. When the city and county park and recreation departments later merged, the county took ownership.

More than 730 acres of forest, field and creek are protected for wildlife, people—and plants—in part because Matthews “has been a fighter for parklands and open space,” says Park and Recreation’s Jim Garges.

“All that research he did during his entire professional life has done nothing but continue to make Mecklenburg County a more sustainable place to live,” said Garges.

Biology, Garges noted, is a Matthews family affair. Not only is Jim’s wife, Betsy, a biologist, now retired from university work, but his son, Christopher, directs the park and recreation department’s Division of Nature Preserves and Natural Resources.

Matthews describes his life’s work in simple terms. “I’ve been fortunate,” he says, “to be able to do exactly what I have the ability to do—and enjoy it.”

‘Until you look’

In the woods at Reedy Creek, Luckenbaugh and Matthews continue their hike, commenting on deer-browsed smilax, stands of black cohosh, an unusual population of royal fern. They note where storm water run-off from nearby Joseph W. Grier Academy elementary school has scoured away vegetation and where a stream shows what Matthews terms beautiful “sinuosity.”

Like all trained botanists, they are careful collectors, never taking a specimen unless sufficient numbers of the species grow nearby and sometimes “top-snatching”—leaving roots intact or, in other cases, taking only a digital image.

The biology professor halts by a patch of Collinsonia canadensis, Canadian horsemint, to deliver a lesson. “If you have a drought,” he says, plants “sit there and regroup.” The drought of summer 2015 yellowed the horsemint and stopped the plant from setting fruit. But during warm late-autumn days, the stand gave it another go, preparing for a second round of blooms. “This,” he says, “is a classic example of ‘Plants don’t give up.’ ”

Matthews, it seems, has taken a lesson from the organisms he studies.

Yes, he says, development’s toll on the region’s plants is disheartening.

“But that,” he adds, “doesn’t keep me from going out in the field. You’ll never know what you’ll find unless you look.”

About James MatthewsProfession: Botanist, retired UNC Charlotte biology professor. Now volunteers his time collecting plants and researching at The James F. Matthews Center for Biodiversity Studies at Reedy Creek Nature Center, Charlotte. Family: Married to Betsy, also a biologist. They have two adult children, Meredith Ross and Christopher Matthews. Chris is division director of nature preserve and natural resources for the Mecklenburg County Park and Recreation department. Favorite plant: Pressed to name one, Matthews says he’s partial to Helianthus schweinitzii, Schweinitz’s sunflower. A federally endangered species, it favors remnant prairies, and its seeds have been known to sleep for years, awaiting a clearing of trees or other event to emerge. Job hazards: “I fell off a cliff one time,” he says. “We were collecting on Rocky River Bluff (in northern Mecklenburg County). A graduate student above me slipped and grabbed me on the way and we both went down. No injuries.” Job benefits: Matthews has been exposed to poison ivy so many times, he says, he’s now immune to it. What he carries: The trunk of Subaru Outback contains boots, plant presses, plastic bags and a cache of ball caps. Quote: “I grew up on a dead-end street in Winston-Salem. I was in the woods all my life… I was a botanist before I knew it.” |