Austin voters approve $7.1B transit plan. Is Charlotte next?

When it comes to Charlotte’s transportation ambitions for the coming decades, the biggest question is simple: How will the city pay for it all?

Austin, Tex., could point to an answer. Voters there approved a $7.1 billion transit plan on Election Day this year, with 58% supporting the referendum. The plan will raise property taxes by about 4% to fund the city’s share of a major transit expansion, including light rail, commuter rail, a tunnel for trains downtown, and expanded bus service.

The community has approved Prop A for #ProjectConnect! We now have a plan, schedule and funding to create a more connected & equitable community. It’s go time! pic.twitter.com/jgRKnnAVTa

— Capital Metro (@CapMetroATX) November 4, 2020

Charlotte’s own “transformational mobility network” will cost somewhere between $8 billion and $12 billion, officials said last month, although that’s just a ballpark figure. The biggest part of that expense would be planned rail lines running east, west, north and south, but the plan would also include improvements to roads, bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure.

The local share is estimated at about half that cost: $4 billion to $6 billion.

[‘You can only make roads so big’: Charlotte region launches its first transit plan]

Earlier this year, the Charlotte Moves Task Force hosted (virtually) officials from three other Sun Belt cities to talk about successes and failures with transportation referenda. Austin was one of the “success” poster children, along with Broward County, Fla. (Nashville was the cautionary tale, after that city’s multibillion-dollar referendum went down in flames amidst a mayoral scandal). Now, Austin’s successful referendum could give Charlotte leaders a bit more confidence to attempt one of their own.

This week, they met again to discuss funding strategies (Watch the video below). They plan to make a recommendation in the coming months.

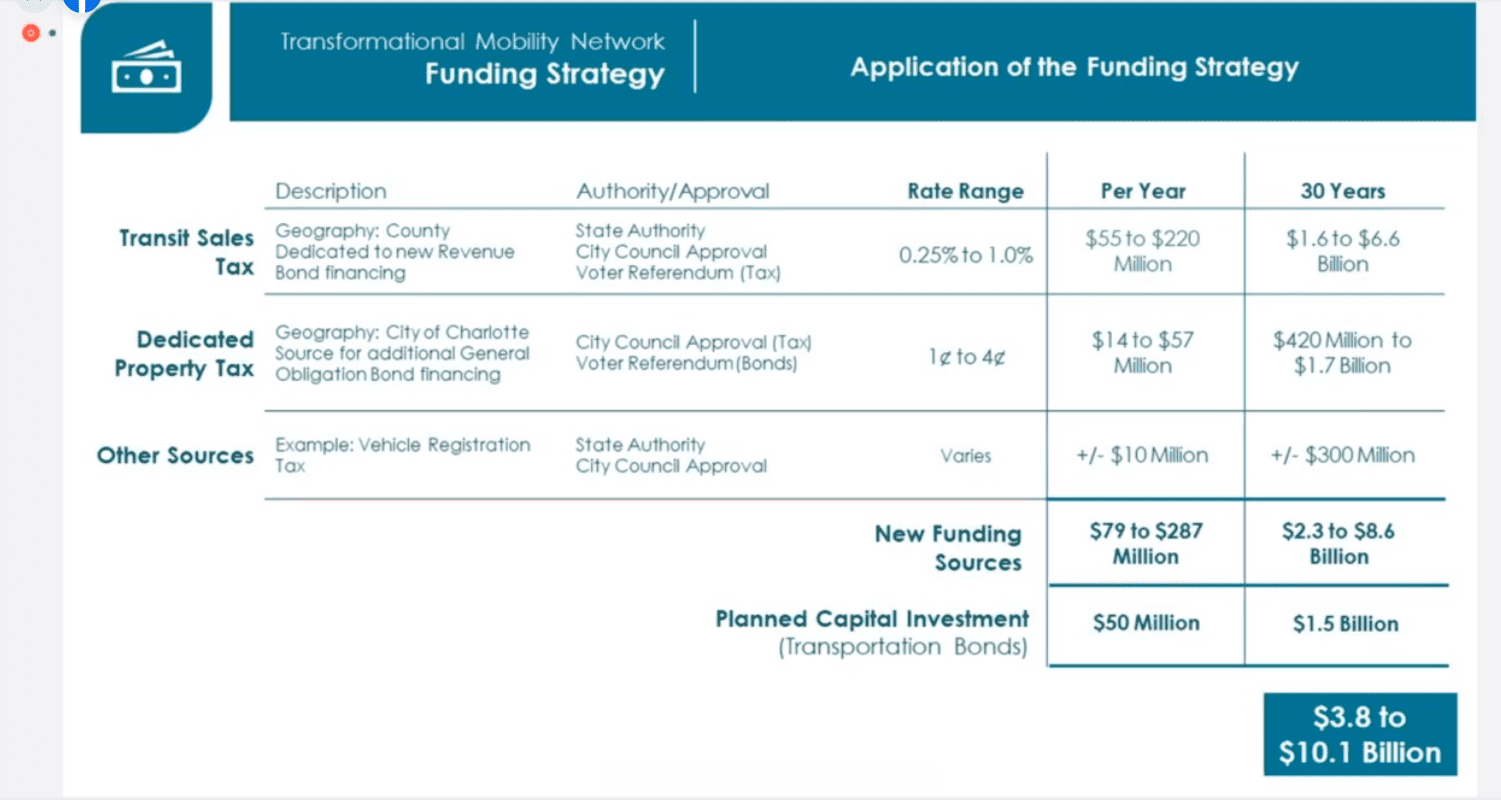

The task force reviewed estimates of how much money different funding strategies could bring in.

Local voters have twice approved a half-cent sales tax in Mecklenburg County to fund the Blue Line light rail. But the current revenue stream isn’t enough to fund a major expansion. Local leaders hope the state and federal government will pick up half the tab, but those grants generally depend on having a steady, local source of funding already in place. So, Charlotte will need to have billions of dollars worth of local funds ready to go before kicking off the plan.

“The debate is going to be how does the average citizen receive this information of what it’s going to cost me in the next 30 years,” said former Mayor Harvey Gantt, chair of the task force. He recalled the “doom and gloom” about the prospects for the sales tax when it was first proposed more than two decades ago.

“We kept trying to paint a more positive picture of what the future was going to look like,” said Gantt. “I shudder to think if that referendum…had lost how far behind we would be with light rail in this city and transportation in general.”

Uh, yeah. I noticed.

— Julie Jacobus Eiselt (@JulieEiselt) November 6, 2020

And despite discussions about options such as public-private partnerships, tax increment financing and other less traditional pots of money, there are really only two local sources big enough to pay for a new transit and mobility network: sales taxes and property taxes.

“The reality is there aren’t that many revenue options that are going to generate enough revenue to satisfy the $8 to $12 billion,” said Kelly Flannery, Charlotte’s chief financial officer, at a meeting of the city’s mobility task force last month. A sales tax increase would require permission from the state legislature and a voter referendum. Raising the sales tax between 0.25% and 1% would generate between $55 million and $220 million annually.

Charlotte City Council could implement a property tax increase to fund transit measures on their own, but they would then hold a referendum to borrow against that new revenue and fund transit projects. Local officials have said they’re still exploring the exact costs and talking to people in the community to gauge support for a possible referendum in the coming years. Each 1 cent increase in the property tax rate would bring in about $14 million a year, the city estimates, at a cost of $21.48 for homeowners at the median value.

Although supporters are pointing to Austin’s success, there are also cautionary tales in the Sun Belt: In addition to Nashville’s rejection, Gwinnett County, Ga., voters turned down a $12.1 billion referendum this year for the second year in a row, saying ‘no’ to expanded rail lines and rapid bus service from Atlanta.

“We don’t know what our community will say,” said Charlotte deputy city manager and chief planner Taiwo Jaiyeoba, speaking in October about a possible referendum, “because we really haven’t tested it.”