Beauty and beasts: Where are Charlotte cankerworms worst?

Tuesday was an almost perfect spring morning: cool, sun coming up and spring flowers ablaze. As I relished a morning walk about 4 miles south of uptown, I also relished something perhaps more gruesome. I gleefully squished dozens of green cankerworms that had fallen onto the street during Monday’s rain.

April in Charlotte is a time of beauty, but the beauty is infested with thousands of little beasts – cankerworms. Like the green pollen coating your car, cankerworms are a significant annoyance even when dogwoods are in gloom, azaleas pop with color and early irises inch open. Don’t know about cankerworms? You may not be from around here. If you think they are cute little inchworms, think again.

Cankerworms, officially known as fall cankerworms or Alsophila pometaria, have been devouring the early spring leaves of Charlotte’s willow oaks, dogwoods and maples for more than 25 years. Their appetite is so rapacious that a serious infestation can all but defoliate not just a struggling young dogwood but a mature oak. I know this because I have seen it happen in our yard, year after year.

Not only do the worms float down on silken threads onto people’s heads, shoulders and clothing, their poppyseed-like excrement can be found on pavement and cars, along with the green pollen.

City arborist Don McSween has been fighting Charlotte’s cankerworms for 25 years. This year, however, for the first time in several decades, he may have found a cankerworm enemy – the fiery searcher beetle, Calosoma scrutator, a native beetle that has begun showing up in Charlotte in unusual numbers and which dines on caterpillars, including fall cankerworms.

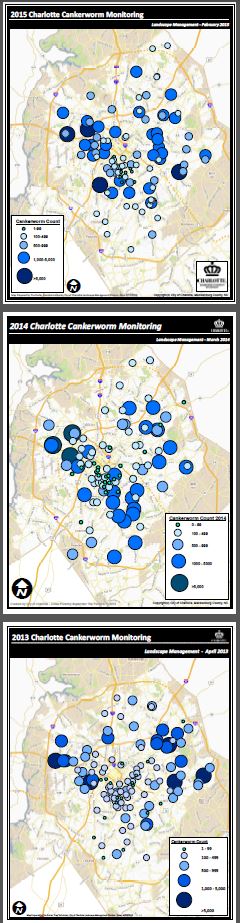

To download larger images of cankerworm infestations 2013-2015, click on images at right. Maps courtesy of City of Charlotte.

Like the searcher beetles, the cankerworms are not an invasive import, such as fire ants or wisteria, but native to this part of North America. And they’ve been causing trouble for centuries. But a typical infestation will abate after a few years. The mystery in Charlotte is why, here, the infestation has continued.

Because the City of Charlotte has an estimated 160,000 street trees in public rights of way, and spends $11.83 per tree – do the math, that’s almost $1.9 million – when an insect threatens to defoliate the trees, the city grows concerned, especially when 16 percent of those street trees are willow oaks, which cankerworms view with the same delight that some folks reserve for bacon cheeseburgers or chocolate ice cream.

In recent years, the city has monitored which parts of town have the worst cankerworm infestations, based on observations of cankerworm traps installed in the late fall on street trees. The traps, also called sticky bands, prevent the adult moths (which hatch after the caterpillars pupate underground during summer and early fall) from climbing to the treetops and laying eggs, which hatch in late March or early April when the weather warms, and begin eating their way down to the ground. The city for 16 years has also encouraged property owners to install the traps on their trees.

This year’s maps show south Charlotte not as badly hit as in years past, but severe infestations continuing in west, east and northeast Charlotte.

In 1992, 1998 and 2008 the city conducted aerial spraying over areas with severe cankerworm infestations, using the organic insecticide Baccillus thuringiensis – a strain of bacteria that will kill caterpillars that eat it.

Why Charlotte? Some researchers’ speculations point to rising temperatures, which mean the worms hatch out earlier, before the arrival of migratory songbirds that would have eaten more of the newly hatched worms than they can eat of the older, larger worms.

Another theory is the lack of plant diversity, or the prevalence in Charlotte of mature willow oaks, which are among the tallest trees in the canopy and, because the cankerworms like to get up high, are more attractive to them. McSween, however, discounts that theory. He explained in an email:

“In the 25 years I have been battling them, I have had several theories dashed by this insect. The monoculture idea was proven wrong when the population exploded around the University/Derita area where you have a large variety of trees.”

Another theory is that urban areas lack the diversity of natural predators. The Fiery Searcher beetle, for instance, is described as being “almost nonexistent in the urban setting.”

However, McSween says, “Last year we were noticing the Fiery Searcher Beetles on the sidewalks at our office” on Tuckaseegee Road. The beetles were also spotted in Dilworth. McSween has encouraged residents to take down the sticky band worm traps early enough in spring – March – so the beetles can climb the trees and eat as many worms as possible – hosting an all-you-can-eat buffet, so to speak.

The cankerworms typically hatch on the first warm, spring day. This video was captured April 3 near Park Road Shopping Center.