Can a community land trust stop gentrification in west Charlotte? This group thinks so.

With a full-time executive director and a $200,000 grant, a three-year-old west Charlotte nonprofit is accelerating its efforts to stave off displacement with a housing strategy that’s unprecedented in this fast-developing city.

In the next five years, the West Side Community Land Trust wants to build 50 permanently affordable housing units in historically black neighborhoods along the West Boulevard corridor. Residents fear many of those neighborhoods will soon become too expensive for them, as development inches ever closer to their homes.

“A lot of communities are feeling the impacts of gentrification and displacement,” said Rickey Hall, a lifelong west Charlotte resident who co-founded the land trust in 2016. “A land trust will offset those avenues for gentrification. You get the type of housing diversity that doesn’t drive people out, but allows them to stay in the community.”

Here’s how it works: The nonprofit raises money to buy land where it can develop houses. The group sells or rents those units to qualified low-income individuals at below-market rates. Residents who buy the homes retain ownership of the house; the land underneath belongs to the trust and, in essence, the community. If a home is sold, some equity goes to the homeowner and some remains with the land trust, which helps the property stay affordable in perpetuity.

Although the model is new to Charlotte, land trusts have existed elsewhere for decades, helping preserve affordability and stall gentrification in cities as big as Boston and as small as Burlington, Vermont. They’ve also kept homes affordable in other North Carolina cities, including Chapel Hill, Durham and Wilmington.

“It’s not only a benefit to homeowners, it’s a benefit to the community,” Hall said. “We need to preserve legacy. We need to preserve the historical and cultural significance of those communities.”

So far, the land trust has purchased one lot on Tuckaseegee Road, where it plans to develop five homes by year’s end, said executive director Charis Blackmon. Property records show the group paid $16,000 for the site. They are working to acquire four other lots, including two from the city of Charlotte.

“If you don’t have the site control, you can’t really do anything. You’ve got to own the land,” said Charlotte City Council member Justin Harlow. “A land trust should just be another tool in our ever-growing toolbox of options to tackle this affordable housing and upward mobility crisis.”

That crisis has left Charlotte with a 34,000-unit affordable housing shortage, by some estimates, as rising costs outpace incomes. A land trust, advocates say, should emphasize creating ownership for people priced out of the market.

“The only way any land trust is going to work is if it’s specific on homeownership,” said Council member LaWana Mayfield, whose district includes much of the land trust’s focus area. “You have people today qualifying for $150,000, $180,000 loans, but none of the housing is coming in that low. We need to produce units at incomes people can afford.”

Earlier this year, the West Side Community Land Trust received a nearly $200,000 grant from the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation that pays for a full-time outreach coordinator, covers operating expenses and pays a portion of Blackmon’s salary. All that will help the group push towards its 50-home goal so it can tackle an even bigger long-term one: 200 affordable homes.

“Our goal is to work as quickly as possible to get those 200 units so we can be self-sustaining and not heavily reliant on external funding sources,” Blackmon said.

Speed is paramount. The land trust still faces a major challenge: raising enough money and rallying enough support to resist a deluge of developers with deep pockets.

‘Getting ahead’ of the changing Queen City

Ask Rickey Hall about the west Charlotte of yesteryear, and he’ll mention churches built by former slaves; all-black schools that were the pride of their communities; and entire neighborhoods developed by the city’s prominent black families.

“If you were poor, you didn’t know you were poor because you had such rich resources, like mutual aid societies and people who made sure you got an education,” said Hall, 62. “It was a village.”

But the village looks different these days.

“Where once these were redlined communities… they’ve become what we call valuelined communities.” – Rickey Hall

Rampant development has sparked a torrent of gentrification. While that can bring new opportunities to struggling areas, it can also displace thousands of people burdened by surging property taxes, home prices and rental rates.

It’s happened in historic minority communities all across Charlotte, from Biddleville to Brooklyn and from Cherry to Grier Heights. It could happen next in Reid Park, where Hall lives in the same house he was born and raised in — the home his grandmother built in 1951. Real-estate investors ask him to sell it on a daily basis.

“You’ll see people actually walking through your neighborhood, going house to house, leaving notes on the door,” Hall said.

For decades, the neighborhoods west of uptown were relatively cheaper and mostly housed minority and low-income families. But as areas clustered around uptown began developing, affluent homebuyers moved in. Now, developers looking for profitable returns are eyeing communities like Hall’s.

Offers from investors to buy houses are common in gentrifying west Charlotte neighborhoods – in person, over the phone, via mail and on telephone poles. Photo: Ely Portillo.

“We’re near one of the biggest economic generators in Charlotte: the airport,” he said. “Look at our close proximity to (uptown). Everybody wants to be close to the skyline now.”

Home prices have skyrocketed since 2011. Property values in just four neighborhoods the land trust is targeting — Reid Park, Lakewood, Camp Greene and Enderly Park — increased by about 63 percent on average, according to a sampling analysis of Mecklenburg County tax records. Individual home values jumped as much as 324 percent and 440 percent in some cases.

And while higher property values don’t necessarily mean higher property taxes (Rates are set separately, though county commissioners did vote to raise them this year), homeowners whose property increased that much are likely to see a jump. And landlords will pass along higher property taxes to renters.

Citywide, the average sale price for a house was $361,455 in June, according to the Charlotte Regional Realtor Association. In June 2014, it was $280,512 – meaning prices have gone up almost 30 percent in five years.

All of that has combined to stoke fears of displacement among residents worried they soon won’t be able to afford living in their neighborhoods.

“We’re looking to get ahead of that,” Hall said. “Once people see the initial proof of concept (of the land trust), then we know support will grow.”

Galvanizing a city

West Charlotte’s land trust won’t go far without engagement from neighbors who trust the model and city officials who offer access to surplus land, buildings and grants, said John Davis of Burlington Associates, a consulting firm specializing in community land trusts.

“Unless the local government is willing to invest in this new approach…it’s very difficult for community land trusts to get over the hump to make a dent in the housing problem,” he said.

Blackmon’s talks with city leaders have yielded positive results, she said, but she believes they can go further.

“They recognize this model, but it hasn’t been integrated into their decision-making yet,” she said.

“We have not gone far enough,” echoed Harlow, the city councilman. Though the city doesn’t own as much surplus land as Mecklenburg County or the school district, it can still help, he said.

“We could allocate…housing dollars towards the land trust,” he said. “I’m hopeful…we can look at funding a model like that, even if it’s just a pilot. Right now, we’re not even trying it.”

When Robert Dowling helped create Chapel Hill’s first land trust in 1998, “there was a close relationship between the local governments and this organization,” he said.

Town leaders required developers to include affordable units in new construction. Community Home Trust buys those homes and sells them at below-market prices across Chapel Hill and Carrboro.

“Now, we have 260 homes in our inventory and they’re all permanently affordable,” said Dowling, the land trust’s executive director.

Some land trust supporters look to bankers to step up to the plate.

“To solve the problem, we need the banks…to create unique loan packages for land trust groups,” Harlow said. “It requires a little less profit on their end and a little less greed.”

‘How can we stop this?’

The West Side Community Land Trust has high hopes for the years ahead, such as expanding into multifamily housing and commercial development, and transforming vacant buildings into mixed-use spaces.

But it faces an obstacle that threatens those long-range plans: Opportunity zones.

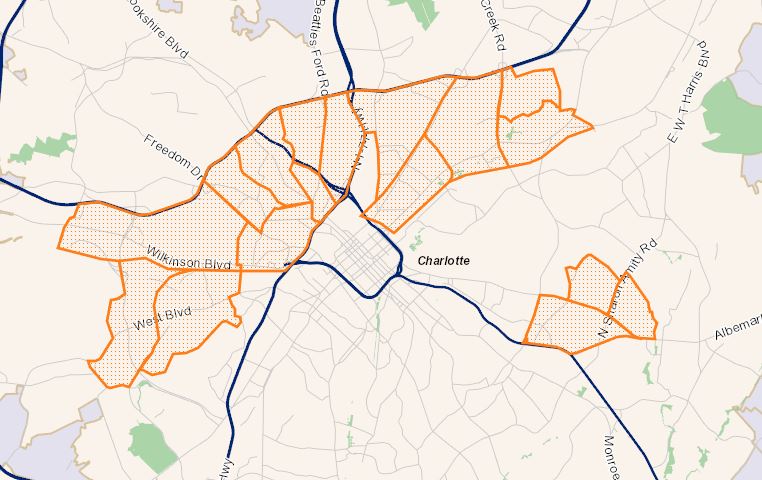

Created in 2017, opportunity zones incentivize developers and real-estate investors to invest in economically-distressed areas in exchange for significant tax breaks. Officials designated 17 zones in Charlotte, most of them in the north and western parts of the city; several intersect with the land trust’s target areas.

Charlotte’s opportunity zones extend mostly west and north of uptown. Source: City of Charlotte.

Charlotte’s opportunity zones extend mostly west and north of uptown. Source: City of Charlotte.

“We expect to see a large influx of development within our focus area,” Blackmon said. “We want to…start acquiring and start holding onto land now, while it’s still low.”

Brenda Campbell and her neighbors in Clanton Park, another neighborhood included in the land trust, are feeling the changes from rising property values. Campbell, 60, worries about whether her property will be affordable by the time her six grandchildren inherit it.

As vice chair of her neighborhood association, she regularly hears from neighbors concerned about shifting dynamics in the community — new apartments, more renters, skyrocketing property values.

“It’s scary,” she said. “My residents want to know: How can we stop this?”

The interest from outside buyers is impossible to miss, between all-cash offers, overtures in the mail and “We Buy Houses” signs on the street corner.

These days, it’s so persistent, Campbell said, “They even call your cell phone now.”

Where land trusts have worked before

Although new to Charlotte, there are about 250 community land trusts nationwide. Civil rights activists pioneered the concept to give black farmers in Georgia their own property in 1969.

- Boston: In the 1980s, residents in the Dudley Street neighborhood organized a land trust to combat illegal dumping on vacant land left behind by a series of arsons. The land trust today owns 225 permanently affordable homes, rental units and cooperative housing units.

- Albuquerque: In 1996, residents banded together to form the Sawmill Community Land Trust to combat rising property values and a particleboard factory polluting their air supply. They developed 34 acres of land on a former industrial site that now includes a variety of housing options, a plaza, park and community center.

- North Philadelphia: In 2010, the Community Justice Land Trust formed in northeast Philadelphia to address neighborhood blight and prevent a booming housing market from displacing neighbors. The nonprofit Women’s Community Revitalization Project banded with a neighborhood coalition to create the land trust, which owns 36 rent-to-own townhomes with plans to create about 70 more across the city.

- Durham: Neighbors founded Durham Community Land Trustees in 1987 to combat the damaging effects of rising housing prices and absentee landlords. It owns about 280 affordable homes across seven neighborhoods.

- Burlington, Vt: City leaders invested $200,000 to start the Burlington Community Land Trust in 1984 to provide affordable housing for low- to moderate-income families. In 2006, the trust merged with a housing development corporation and expanded its reach to three counties. Today, the Champlain Housing Trust is the largest land trust in the nation, with nearly 3,000 affordable apartments and owner-occupied homes in its inventory.

Jonathan McFadden