Charlotte leaders are looking for regional cooperation — and funding — to restart stalled transit expansion plan

Charlotte’s transit plan is dead — long live the Charlotte region’s transit plan?

It’s been almost two years since the $13.5 billion Charlotte MOVES plan was unveiled, and there have been weeks of hints that changes are coming to the city’s plan for expanded rail, bus and other transportation options. Now, the shape and scope of Charlotte’s revised plans is becoming clear. In a reversal of its previous strategy — building buy-in and regional support for a plan Charlotte devised on its own — leaders signaled this week that the new plan will have regional cooperation at its heart from the beginning.

“We can’t just bring the plan we developed to them (regional partners) and say ‘there it is,’” said Charlotte City Council member Ed Driggs. And he said a regional authority of some kind would be required. “We needed to have a regional plan…We’re going to have to create some sort of an organization for the issuance of debt.”

[Register now for a virtual panel: What’s the path forward for transit in Charlotte?]

Driggs spoke in Ballantyne at the South Charlotte Partners Transportation Summit (at which the Transit Time team anchored a panel) on Monday.A Republican on a 9-2 Democratic board, his opinion might not seem to carry that much weight — except that Driggs is the newly-appointed chair of the council’s transportation committee and the city’s representative on the Charlotte Regional Transportation Planning Organization.

In short, he’s the guy Charlotte Mayor Vi Lyles handed the reins to for much of Charlotte’s transit and transportation policy. Official after official echoed his thoughts.

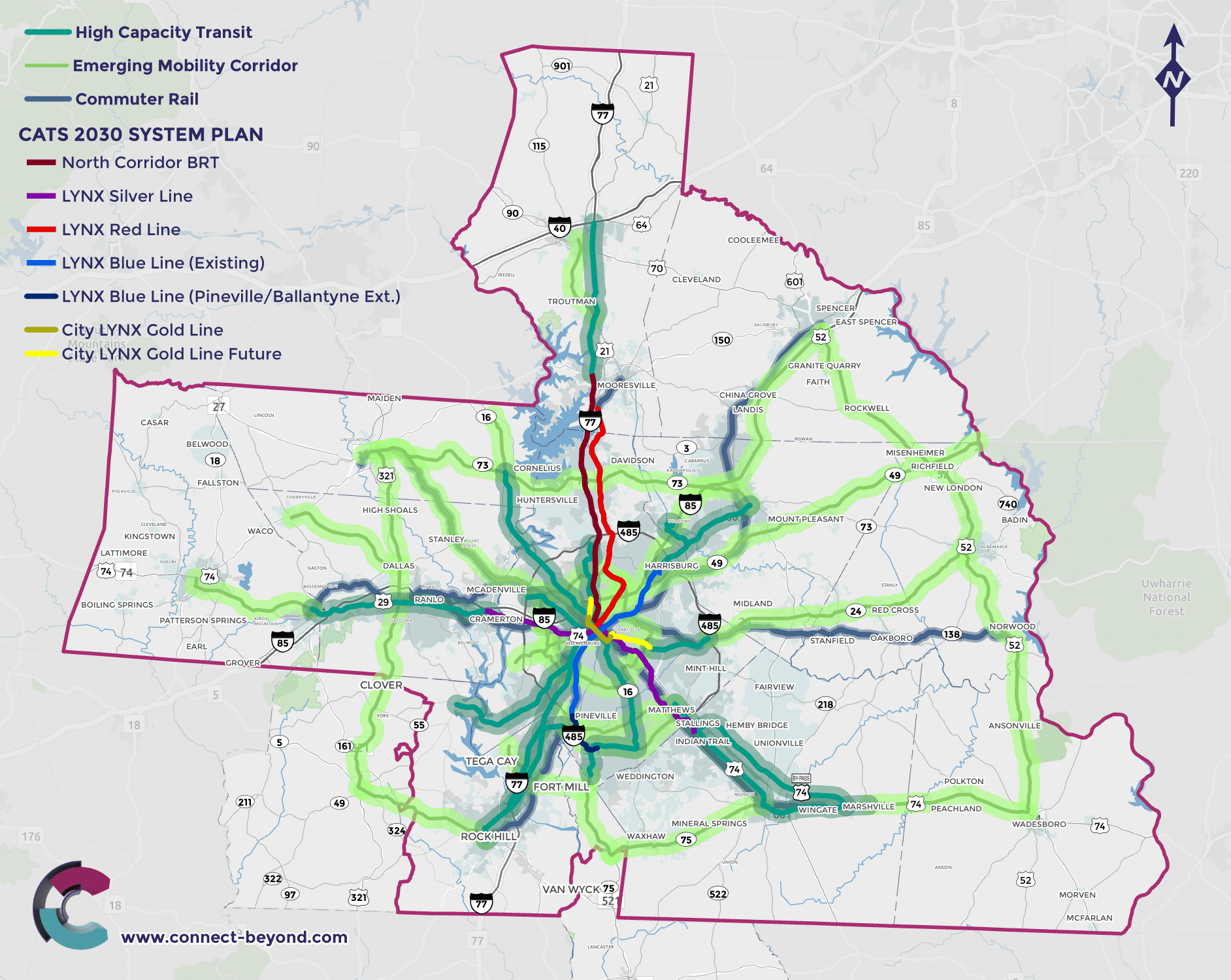

Mayor Vi Lyles didn’t advocate for Charlotte MOVES or the one-cent sales tax referendum needed to fund it — but she did speak approvingly of Connect Beyond, the regional, largely bus-based transit plan led by the Centralina Regional Council: “We need to approve of Connect Beyond and put our full force behind it.”

State Sen. Wesley Harris, a Democrat, emphasized that a regional approach and working with the towns and largely Republican-controlled counties surrounding Charlotte, will be essential to getting the General Assembly’s support.

“It’s not going to be a situation where Charlotte says ‘this is our plan — fund it or don’t fund it,’” he said. “It has to be seen as a mutually beneficial thing.”

Geraldine Gardner, executive director of the Centralina Regional Council, pointed out a number of advantages to focusing on the Connect Beyond Plan. It can be phased, with short-term, low-cost ideas like synchronizing regional bus fares, and involving rural and exurban communities will get Republican leaders from those communities on board.

“We have a regional transit vision,” she said. Of a Charlotte-only approach, Gardner said: “We’re not going to make any progress.”

Not a surprise

Adopting a more regional approach to Charlotte’s transit and transportation needs isn’t exactly a shocker. With half of Mecklenburg workers commuting in from another county (pre-COVID, at least), an approach that’s not regional doesn’t make much sense. The city’s transit plan calls for a Silver Line light rail that would reach into Gaston and Union counties, as well as the Red Line commuter rail to Mooresville, and contemplates extending the Blue Line north to Cabarrus County.

But the new tone from Charlotte officials is a change, and maybe even a repudiation, of their earlier approach.

When Charlotte rolled out the current transit plan in late 2020, it was the result of a task force created by Lyles and chaired by former Charlotte Mayor Harvey Gantt. The task force issued its report and recommended that Charlotte seek a one-cent sales tax in Mecklenburg County to pay for the local share of costs. And then local officials set about estimating the costs and seeing if other communities were interested.

To build a regional light rail line, CATS would need funding from Gaston and Union counties. Officials from those counties have generally said they support the idea, but haven’t stepped forward with offers of money. And to build the plan at all, Charlotte needs the legislature’s permission to put a sales tax hike on the ballot in Mecklenburg, not to mention voters’ approval. With no movement in the legislature — indeed, with no formal ask from Charlotte for a referendum — the city is flipping its approach.

[Shrinking Charlotte’s transit ambitions to get something built]

Whatever comes next for the transit plan will start with regional involvement in the planning, funding and decision-making process. Rather than presenting a plan and then trying to get buy-in from surrounding regions, Charlotte seems now to be prepared for the opposite tack.

Driggs pointed out that a regional plan would stand a better chance of receiving federal funding. That’s key, because even if Charlotte were to get a new sales tax, the revenue would only pay for 60% of the plan’s cost — with the feds expected to pick up the rest of the tab.

“For that federal funding, we need to present a plan that is regional and fully funded,” said Driggs.

So, does this mean it’s back to the drawing board? Not completely. The Connect Beyond plan has been developed in tandem with CATS (albeit with a lot less fanfare than the city’s plan), and it offers a framework the city and surrounding counties can pursue. Connect Beyond emphasizes the regional role of bus transit, integrating the 17 different local transit agencies and creating synchronized schedules, operations, fare structures and bus routes. The plan also calls for enhanced rural connections, more transit-supportive planning throughout the region, and for exploring regional sources of funding.

Charlotte could put its full weight behind Connect Beyond while also trying to figure out how to pay for some of its own transit ambitions (perhaps a slimmed-down version of Charlotte MOVES, or one that spends more on greenways, bicycle infrastructure and sidewalks than rail).

Whatever happens next for Charlotte’s transit plan, it seems clear the city no longer thinks going it alone is an option. And local leaders are acknowledging Charlotte faces a long and uncertain road ahead. Driggs referenced two failed attempts by Austin to pass bond referendums for transit, in 2000 and 2014, before the city finally won approval for a $7.1 billion plan in 2020.

Said Driggs: “Maybe the Austin thing couldn’t pass until conditions on the road got bad enough that everyone was ready to write those checks.”

This story was published as part of Transit Time, a collaborative newsletter produced by the Charlotte Ledger, WFAE and the Charlotte Urban Institute.