Charlotte transit stations: realizing development potential?

Development patterns along Charlotte’s Blue Line, which opened in November 2007, show a mixed bag of more low-density neighborhoods than planners recommend, but still a blend of homes, workplaces and stores. That means the corridor is brimming with opportunity for its 15 station areas to develop more intensely, and in a way that puts walkable, diverse urban neighborhoods near transit.

The basic concept of transit-oriented development (TOD) is to put homes, retail, services, and work places close to transit stops. In theory, this provides places where people can “live, work and play” without depending on a car. Along the Charlotte LYNX Blue Line, we’ve got the “T” (transit), but an analysis of the areas surrounding its stations shows plenty of room for more “D” (development). Indeed, the average density along the Blue Line is 3.67 housing units per acre, well short of the recommended densities for TOD.

I rode the 9.6 mile Blue Line from the heart of uptown Charlotte at Seventh Street (after a delicious lunch at 7th Street Public Market), south to Interstate 485 at the edge of Pineville, and back. The variety in my fellow riders was matched by their accoutrements – strollers, coolers, shopping bags, suitcases and bicycles. We whisked quietly through landscapes of urban condos, restaurants, factories and strip shopping centers alternating with small patches of woods, highway overpasses, and older brick-clad manufacturing districts.

I rode the 9.6 mile Blue Line from the heart of uptown Charlotte at Seventh Street (after a delicious lunch at 7th Street Public Market), south to Interstate 485 at the edge of Pineville, and back. The variety in my fellow riders was matched by their accoutrements – strollers, coolers, shopping bags, suitcases and bicycles. We whisked quietly through landscapes of urban condos, restaurants, factories and strip shopping centers alternating with small patches of woods, highway overpasses, and older brick-clad manufacturing districts.

I explored the areas around several stations to test-walk their neighborhoods. I was looking for evidence of TOD – the intended heart of the 2025 Integrated Transit/Land Use Plan that envisioned five primary transportation corridors, including the Blue Line.

For many cities the challenge of inserting rail into pre-existing urban areas leaves transit, and TOD, “DOA.” Charlotte has been able to overcome this obstacle by using existing rail lines and rights-of-way already in place. This money- and time-saving approach brings transit through opportunity-rich parts of the city, where most of the area’s development predates the rail.

Although densities around stations today are low, their locations are ideal for urban infill projects and densification. Ground was broken on July 18 for the Blue Line Extension (BLE), a 9.3-mile route set to connect the UNC Charlotte campus with uptown by 2017. Plans continue for additional connections via the long-proposed, but still unfunded, 30-mile Red Line commuter rail to north Mecklenburg and southern Iredell counties. (Click here for a fact sheet and map of the proposed Red Line corridor; and here for a map of the BLE.) The fast-growing towns of Davidson, Cornelius, Huntersville and Mooresville have planned for more pedestrian-friendly and TOD-style development in anticipation of rail extension by adopting form-based codes. Form-based codes are based on the desired form development will take, and worry less about uses and more about the shape of space – such as proportions of width to height, and how buildings relate to the street. Conventional zoning regulates where development can happen by separating uses – residential here, commercial there, etc. – but with less consideration of what that development will look like.

So, just who’s using the Blue Line, and what kinds of neighborhoods do they come from?

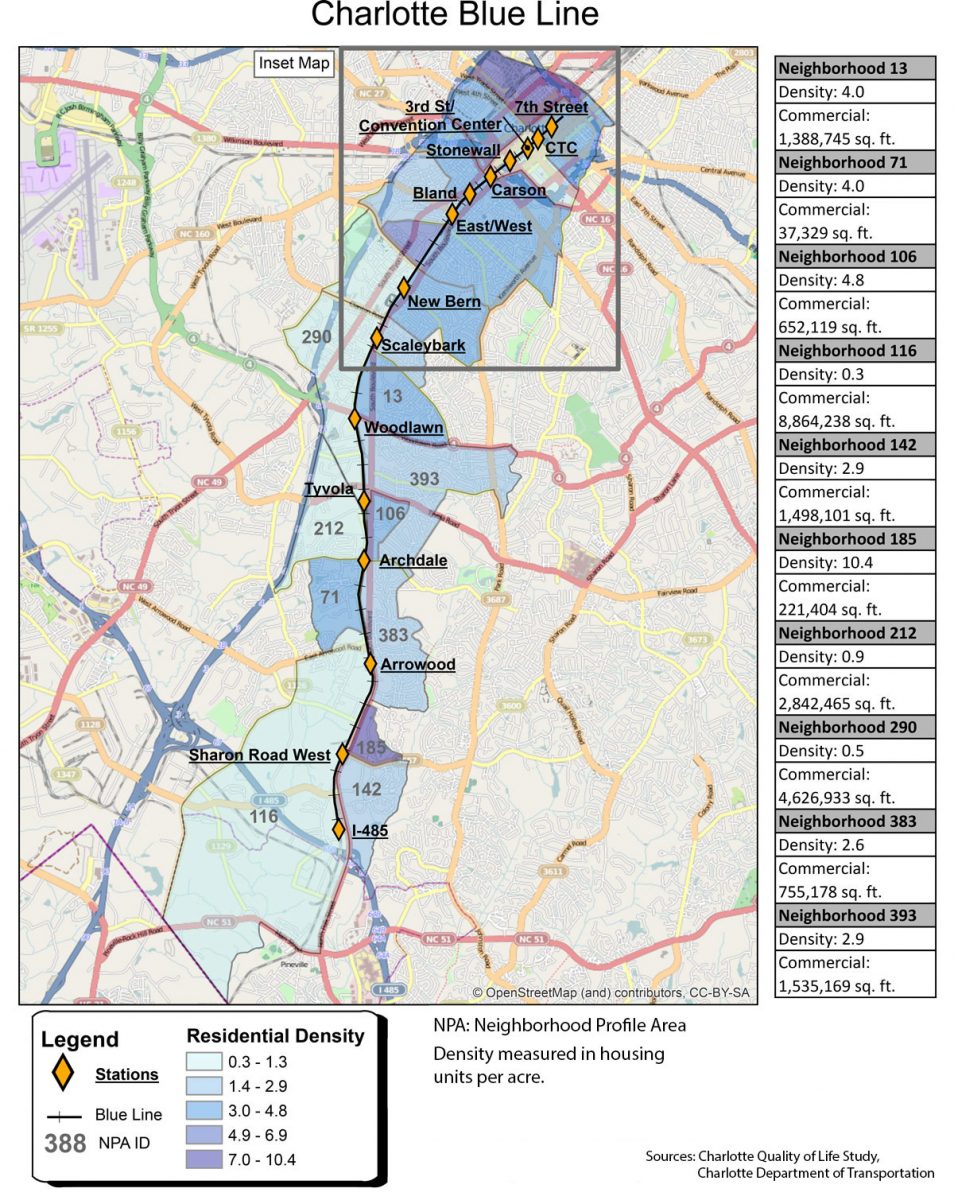

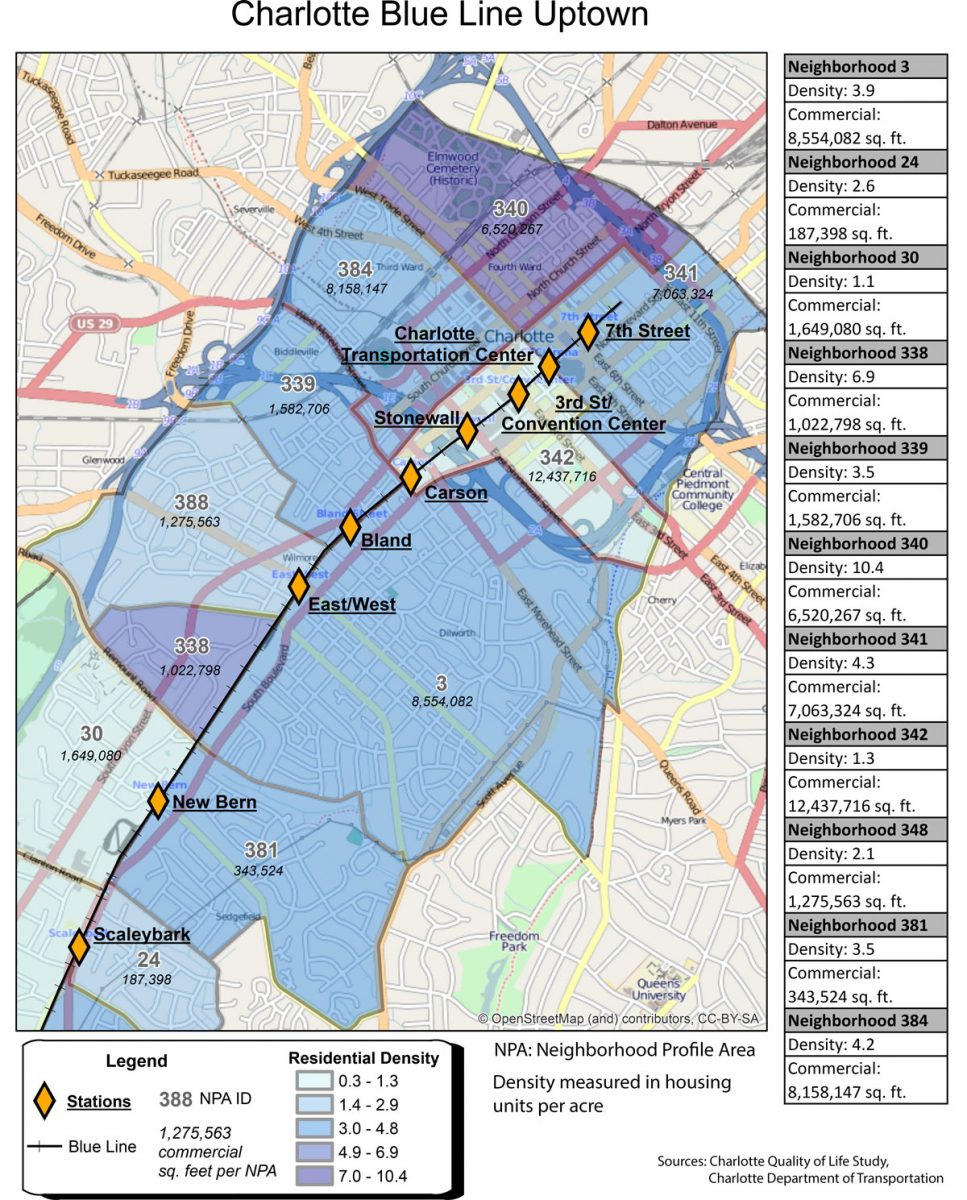

To gain some insight, I gathered data surrounding each of the 15 stations from Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s 2012 Quality of Life (QofL) study, including economics, development patterns and commuting habits. The study uses neighborhood profile areas, or NPAs, which are based on census blocks.

(The article continues below the map).

The 21 NPAs adjacent to the stations contain nearly 54,000 people and 30,000 homes, with an average of 99.5 percent of those homes within one-half mile of a bus, express bus or rail transit stop (known as the “transit zone”). From these neighborhoods, more than 44,000 people board some form of transit every weekday. Residents around the stations tend to be younger, with a median age of 32, compared to the county’s median age of 35.3 and the city of Charlotte’s of 33.3 years of age.

The median income in the Blue Line transit zones is $43,186 – less than the county median income of $61,973 and the city median of $53,146 – a finding typical of neighborhoods near transit in a nationwide study by the Center for Transit-Oriented Development. Of the 21 NPAs that surround Charlotte’s stations, the Carson and East/West transit zones have incomes higher than the county median – each at a little more than $64,000 – as does Seventh Street at $72,393. The average rent around stations ($794) is also considerably lower than the county’s average ($948).

The median income in the Blue Line transit zones is $43,186 – less than the county median income of $61,973 and the city median of $53,146 – a finding typical of neighborhoods near transit in a nationwide study by the Center for Transit-Oriented Development. Of the 21 NPAs that surround Charlotte’s stations, the Carson and East/West transit zones have incomes higher than the county median – each at a little more than $64,000 – as does Seventh Street at $72,393. The average rent around stations ($794) is also considerably lower than the county’s average ($948).

A key part of transit-oriented development is higher densities within a 10-minute walk (a half-mile radius) of stations to provide more housing closer to transit, which allows people to make fewer trips by car. On average, 76.2 percent of Mecklenburg County residents commute alone by car to work, and 34.9 percent have a 30-minute or more commute. U.S. Census data show that within the city of Charlotte, 77.2 percent commute to work alone by car, while only 3.7 percent use public transportation. These numbers tell us that residents living within the Blue Line transit zones use transit more and cars less than the county and city averages as a whole (see table below).

| (Averages) | Commute by car alone | Commute ≥ 30 minutes | Daily Transit Boardings |

| All Blue Line Transit Zones | 63.5% | 23.48% | 2,102 |

| Mecklenburg County | 76.2% | 34.3% | 165 |

Looking at median income levels, average rents, housing values and use of transit shows that the Blue Line serves residents of many different stations in life, including those with lower incomes who need public transportation most. I saw this reflected in my fellow passengers on the Tuesday afternoon trip, who boarded wearing business attire, flip flops, in uniform, or grasping a sippy cup.

(The article continues below the map).

Accepted standards for TOD densities are 15 units per acre for frequent bus service, and 9 to 12 units per acre for rail. The Lexicon of the New Urbanism by Duany Plater-Zyberk & Co. calls for a minimum of 14 units per acre for rail TODs. The average density around Charlotte’s Blue Line stations at 3.67 units per acre is a far cry from the recommended minimums and one more consistent with low density, single-family residential development. The Blue Line transit zone densities range from 0.3 to 6.9 units per acre in all but two NPAs, where at 10.4 units per acre each, density begins to approach the recommended minimum. Overall average density drops to 2.96 units per acre when excluding the highest density as an outlier.

The transit zones east of Sharon Road West and north of Seventh Street stations have the highest surrounding densities, each at 10.4 units per acre. However, the Sharon Road West transit zone is bisected by South Boulevard – a major thoroughfare – and touches three different NPAs. To the west, density is a mere 0.3 units per acre, and to the south, density is 2.9 units per acre. A split in density also exists at the Seventh Street station, where the area to the north is 10.4, and to the south, 4.3 units per acre.

The transit zones east of Sharon Road West and north of Seventh Street stations have the highest surrounding densities, each at 10.4 units per acre. However, the Sharon Road West transit zone is bisected by South Boulevard – a major thoroughfare – and touches three different NPAs. To the west, density is a mere 0.3 units per acre, and to the south, density is 2.9 units per acre. A split in density also exists at the Seventh Street station, where the area to the north is 10.4, and to the south, 4.3 units per acre.

Although the southernmost station at I-485 near Pineville has the lowest surrounding density overall (0.3 units per acre), it also has the highest number of daily transit boardings at 6,135. As a park-and-ride station, commuters from more distant neighborhoods board here to ride directly into uptown Charlotte along the Blue Line. Today this area is not well developed, but it is likely to grow and lies in a logical location for future rail extension.

Two successive rail stations, Scaleybark and New Bern, fit the age-old description of living on the right- or wrong-side of the tracks. To the east of these stations, home values average in the low $200,000s. To the west, they average $76,000 and $56,000. At New Bern station, though, things may be changing.

Fountains Southend at the New Bern station takes TOD up a notch. It is a new, 208-unit, luxury apartment development that is not only TOD by location – the building itself is TOD. Just behind its lobby and steps from the Blue Line is the “light rail lounge and Starbucks coffee bar.” From here, wall mounted monitors let residents watch for approaching trains via camera feeds pointing up and down the tracks. Among the Fountains amenities are a virtual fitness lab, pet spa and pool-side bar.

“Access to the Blue Line is definitely a big draw,” said Anita Balawejder, the assistant community manager at Fountains. “About 80 percent of our residents are uptown commuters.” Construction got underway last year, and the second phase is nearing completion. “Leasing began in February, and we filled up almost immediately. In Phase II, 80 percent are pre-leased,” said Balawejder.

There’s more to TOD than just housing: It’s also about connecting people to commercial activity and employment destinations. The transit zones of the Blue Line contain more than 71 million square feet of commercial space (including the uptown office towers), with 12.5 million square feet of it easily accessed by the Carson, Stonewall or Convention Center stations. Another 8.9 million square feet are within the I-485 station’s transit zone; seven other stations are accessible to more than 7 million square feet of commercial space each. Employers along the Blue Line range from Pepsi to Lance to the Bank of America corporate headquarters.

As my afternoon drew to a close, the air-conditioned ride back to uptown was a welcome relief from the day’s intense heat. It gave me time to reflect on the slice of Charlotte life I had observed. The Charlotte Area Transit System is going a long way in coupling residential origins with commercial destinations, but there is plenty of room to spare for its transit zones to grow into a more TOD-type model.

As my afternoon drew to a close, the air-conditioned ride back to uptown was a welcome relief from the day’s intense heat. It gave me time to reflect on the slice of Charlotte life I had observed. The Charlotte Area Transit System is going a long way in coupling residential origins with commercial destinations, but there is plenty of room to spare for its transit zones to grow into a more TOD-type model.

But for now, along most of the Charlotte LYNX line, it’s more T than TOD.