Is Charlotte’s bike plan update good enough?

Are master plans really worth the effort? Skeptics discount them, charging that they are little more than feel-good exercises in wishful thinking. Such critiques have currency for some plans but not all. When done right, a plan states which policies are more important and includes metrics to gauge outcomes; it charts timelines for putting recommendations into effect, and forecasts a verifiable budget.

Although Charlotte’s proposed new plan, Charlotte BIKES – awaiting City Council approval – and the 2008 plan it would update both tackle those multiple objectives, they do so with varying degrees of success and within contrasting contexts. To their credit, both the 2008 bicycle plan and Charlotte BIKES, address these criteria systematically. (Update: The City Council approved the plan May 22.)

Click image to download proposed bike plan.

Click image to download proposed bike plan.

The good news is that the updated plan improves on its predecessor in many ways, especially in response to a more enlightened and proactive local biking community. Its shorter, more visually appealing format is more readable and user-friendly. Nevertheless, elements of concern remain that beg further consideration. Some have been anticipated by Charlotte Department of Transportation staff and the Bicycle Advisory Committee, a citizen-based stakeholder group. (Disclosure: I’m a member of the committee, although the opinions here are mine, not necessarily those of the committee.)

Bike plans in Charlotte are supposed to occur on five-year cycles, although this update took nine. Several factors contributed to the lengthy delay, including funding shortfalls related to the economic downturn that hit in 2008 and the retirement last May of Ken Tippette, the capable CDOT planner who managed the 2008 plan. The update awaits a final blessing by Charlotte City Council on Monday, May 22. Public support has been strong at a recent public hearing and in testimony from the bicycle committee.

Everyday cycling in Charlotte was still in its infancy in 2008 despite advances on several fronts. Progress on the ground by then amounted to 51 miles of bike lanes, 20 miles of greenways and 4 miles of neighborhood signed routes. A growing advocacy movement had gained some traction, and it was not that difficult to participate in a variety of recreational rides, sign up for bike-education courses or take part in special events like the annual Mayor’s Ride. Those gains were factors in Charlotte’s attaining a bronze level ranking from the League of American Bicyclists as a “bicycle friendly” city in 2008.

But the fact remained that the weekend spandex crowd dominated the local scene – typically middle-aged, Caucasian, male and residing in affluent neighborhoods south and southeast of uptown. The popular “24 Hours of Booty” charity ride each year in upscale Myers Park reinforced this, along with a concentration of bike shops nearby.

Recruiting new cyclists regardless of age, income level, gender or neighborhood to try everyday cycling remained, at best, a laudable but elusive goal. Yes, bicycling could be fun on a sunny weekend, but the idea of cycling to school or the grocery store meant altering entrenched car-dependent habits. The notion of living without a car was, well, laughable.

The updated plan reflects a much more favorable cycling environment. Recent breakthroughs include the B-Cycle bike-sharing network, a successful city bond referendum to fund planning studies for the proposed Cross Charlotte Trail, and generous support from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation on many fronts, including a new bicycle advocate post at Sustain Charlotte, jump-starting the car-free street festival Open Streets 704 and importing international experts such as Gil Peñalosa and Janette Sadik-Khan to inform and energize local audiences.

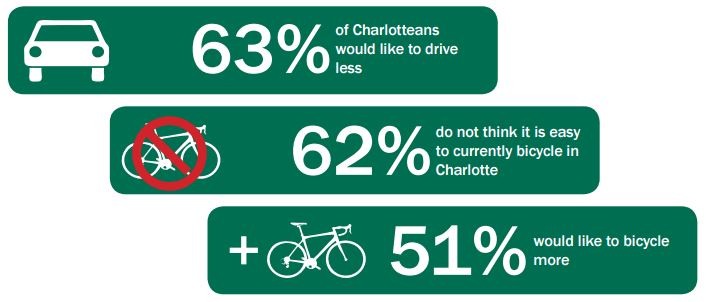

Results from a 2016 survey by the Charlotte Department of Transportation.

Results from a 2016 survey by the Charlotte Department of Transportation.

Here are a few key differences between the two plans:

1. The 2008 bike plan weighed in heavily on engineering (i.e., infrastructure), geared toward a 750-route-mile buildout by 2030. But it downplayed the four non-engineering components considered essential for overall success: education, enforcement, evaluation and enforcement. Charlotte BIKES strikes a better balance between all five E’s and adds a sixth: equity. It also assigns budget values to each category.

2. The plan update dramatically increases the long-term budget recommendation, more than doubling it from $47.5 million over 25 years to $100 million. That amounts to a hefty $4 million average per year, of which the annual non-engineering portion increases from roughly $240,000 to $330,000.

3. The new plan embraces updated national design standards from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO). Those include separated bicycle lanes (also called protected bike lanes or cycle-tracks) on busier streets.

4. The update puts greater emphasis on safety elements. The goal is to ensure that cyclists from age 8 to 80 can ride with comfort regardless of skill level. It endorses “Vision Zero,” a new safety concept based on the ethical principle that no loss of life is acceptable.

5. The plan progresses beyond opportunity-driven facilities, such as bike lanes funded by being piggy-backed to road-widening projects, and toward the more challenging (and expensive) stand alone projects. Projects in the mix might include parts of South Boulevard, Parkwood Avenue and the Uptown Connects Study, although funding sources are yet to be identified.

Commuting by bicycle remains rare in Charlotte. This 2009 photo shows one commuter who prefers the sidewalk uptown, although uptown is one area where, unlike most of Charlotte, city ordinance prohibits bike-riding on sidewalks. Photo: Nancy Pierce

Commuting by bicycle remains rare in Charlotte. This 2009 photo shows one commuter who prefers the sidewalk uptown, although uptown is one area where, unlike most of Charlotte, city ordinance prohibits bike-riding on sidewalks. Photo: Nancy Pierce

And what elements of concern remain? Three of the most pressing:

Budget shortfall. All funding other than engineering is ostensibly sourced via city operating funds. In reality, funding has never been approved other than for annual Bike! Charlotte activities. Unless a reliable source for such funds is identified and earmarked as a dedicated annual allotment, the balance sought in the current plan between all five E’s is at great risk.

Poor network connectivity. A 2014 Knight Foundation-sponsored community dialogue cited especially poor connectivity as a high-ranking concern. It’s a key reason the “interested but concerned” people who make up the majority of wannabe cyclists simply don’t choose to ride. Numerous orphan lanes have been built that abruptly end, fail to connect to subsequent bikeway segments or lack accessible links from on-road to off-road greenway routes. Correcting those deficiencies could be a huge and costly task, requiring an in-depth look to define the true scope of this problem.

“Bicycle Friendly” ranking. The proposed plan targets year 2020 to advance from bronze level to the coveted silver “bicycle friendly” status. This hinges in large part on whether the Queen City can quickly increase the number of everyday cyclists from a lowly .03 percent level to 2 percent or 3 percent levels. CDOT has begun tracking local ridership instead of defaulting to national census data that measure commuting modes. But the ridership metric is only one of several needed to win a higher ranking. For now, silver level remains a performance target with no clear strategy on how to meet it.

Should these continue to be unresolved, the goal of “pushing the city to become as bike friendly as possible, as quickly as possible” could fall far short of expectations.

It’s likely the City Council will approve the plan update Monday. That will mark an important step forward, but it is largely symbolic. The heavy lifting must come later.

Martin Zimmerman is a member of the Bicycle Advisory Committee and has been a stakeholder for three bike plans. The opinions expressed in this article are his own and do not necessarily reflect the committee as a whole.