Charlotte’s losing its green canopy, despite efforts to save trees

Charlotte is losing over three football fields a day worth of trees.

That’s the sobering conclusion of a study by the University of Vermont in collaboration with TreesCharlotte, detailing how development, age, storms and other factors have cut down Charlotte’s tree canopy. The percentage of Charlotte covered by tree canopy fell from 49% to 45% of the city between 2012 and 2018.

“Overall, the City has a robust amount of tree canopy but it is under threat, with a marked decline from 2012 to 2018,” the report concluded. After accounting for growth that made up for some of the trees cut down, the net loss of 7,669 acres of trees translates to 8% of the city’s canopy, or an estimated 250,000 trees.

Those findings contrast with a 2017 study by consulting firm Plan-It GEO, which used a different methodology to conclude that the city’s tree canopy hadn’t statistically changed between 2012 and 2016.

The loss of trees has left Charlotte — long known as a city shaded by majestic oaks, towering maples, abundant elms and longleaf pines — wrestling with how to preserve or increase its tree coverage as the city grows. Trees provide benefits beyond their aesthetic value: They reduce air pollution, filter our water and help lower temperatures in a world that’s getting hotter, especially in urban “heat islands.”

“We need trees,” said Chuck Cole, executive director of TreesCharlotte. He said it can be difficult to get people to understand the benefits of a healthy tree canopy — especially given that Charlotte still has more trees than many peer cities. “People open the front door and they say ‘I see plenty of trees. What’s the problem?’”

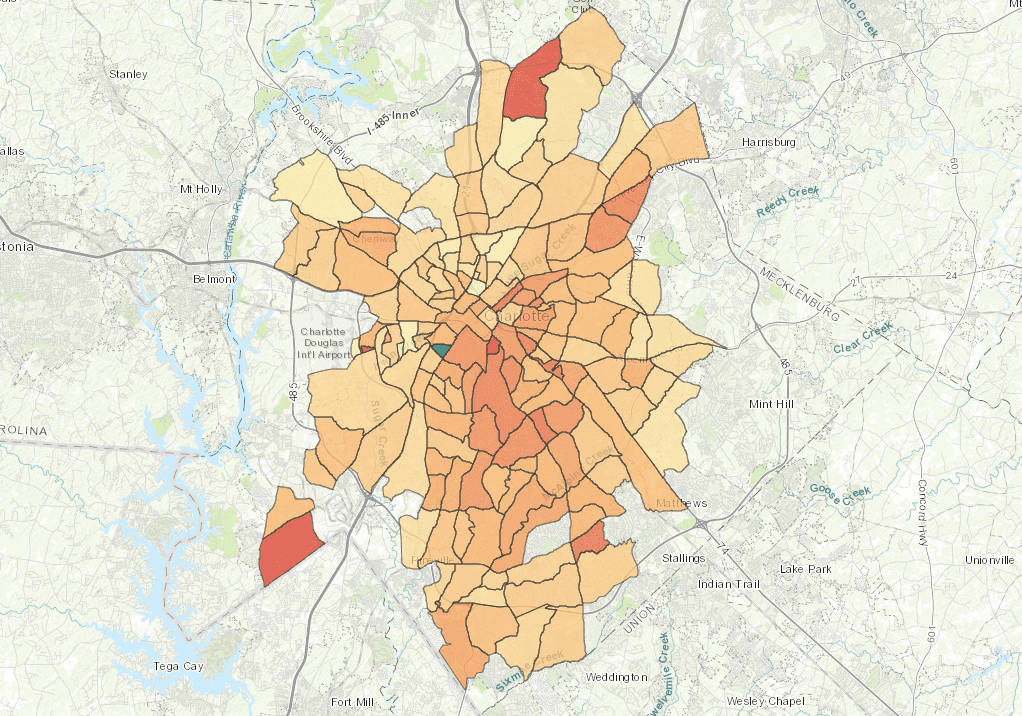

Interactive map: Explore Charlotte’s tree canopy loss by neighborhood

Spurred on by an earlier study in 2012 that showed the tree canopy under pressure, the city’s previous goal was “50 by 50,” or reaching 50% tree canopy coverage in Charlotte by 2050. But last year, the city backed off that goal because it appears increasingly unrealistic, given the amount of development in Charlotte.

“It was an aspirational moment when ‘50 by 50’ was adopted by the City Council, but it was never tied to any regulatory aspects of land use planning,” said Dave Cable, local tree advocate. “The 10% tree save ordinance mathematically can’t even begin to keep up with the pace of development.”

“We must link our vision, of what we want our neighborhoods to look like, to land use policy now, or we will regret it in 20 years.”

This year, the city is developing a new “Tree Canopy Action Plan.” It’s designed to complement the city’s new 2040 Comprehensive Plan and Unified Development Ordinance, both of which City Council is expected to consider next year.

“Out of it will come new canopy policies,” deputy planning director Alyson Craig told Charlotte City Council’s Transportation, Planning and Environment Committee last month. The city’s current tree policies are largely remnants from past eras.

“It’s a suburban ordinance that doesn’t fit an urban city we’ve become now,” said Craig.

As part of the tree canopy action plan, a stakeholder group of developers, neighborhood advocates and environmentalists have been meeting (virtually, due to the coronavirus pandemic) this summer. They’re considering how new tree regulations will fit with the city’s broader ordinance rewrite — which is meant to simplify and combine development regulations — and other priorities, such as developing affordable housing and transportation.

Uptown Charlotte, seen in the background, looking west along Independence Boulevard. Charlotte is known for its lush tree canopy. Photo: Clayton Hanson

Tim Porter, the city’s arborist, said the University of Vermont study using aerial imagery and laser measurements is “the first real confirmation” of the size of the declining tree canopy in Charlotte.

“This is the first one to show a marked decline,” Porter told the city council committee. “That’s really informing our stakeholder group.”

Council members said they expect the challenges to get more severe as the city’s rapid growth continues.

“We’re talking about 50% population growth by 2040,” said committee member Ed Driggs, “And that’s going to involve some tough choices around trees.”

Jarring losses, smaller gains

Urban tree canopy is understood as the area of the city shaded by trees, and is a key quality of life indicator. This latest study shows how hard it will be just to maintain what we have now — much less add thousands of acres.

Details from the University of Vermont study include:

- Most canopy loss between 2012 and 2016 occurred on residential land, at 65%, followed by public right-of-way trees at 5%. That makes sense, because most of the city’s tree canopy is located on private land designated for residential use. The study concluded that construction likely accounts for much of this (obviously through the removal of large tracts of trees), but many of the trees removed from residential areas and right-of-way could be victims of age, storms, disease or other factors.

- Charlotte added 2,195 acres of tree canopy over this same time period. That wasn’t enough to make up for the loss, however, which totalled 9,864 acres — almost 4 acres a day. But it does show that we’re not seeing a uniform decimation of the canopy. For example, the study pointed to areas such as those around Freedom Park, where there are both losses associated with new construction and individual additions of new trees scattered throughout neighborhoods.

- Some surprising losses occurred in areas guaranteed not to be cut, such as post-construction buffers around streams.

- While Charlotte is losing large tracts of trees, additions are occurring in smaller chunks. “Gains were largely limited to individual trees and small patches whereas losses ranged from individual trees to large tracts of forested land,” the report noted.

It all adds up to a nuanced picture of a city that’s trying to find a new balance for its tree canopy.

“I hope this report acts as a rallying call for both businesses and the City,” said Rob Phocas, Corporate Social Responsibility Director for AvidXchange, and the city’ former sustainability director. “Charlottes’ trees are definitely a selling point for recruiting people. Anyone who flys in, or looks out an office window, thinks, ‘Wow…this is a city in a forest!”

“The timing is also perfect for the City to link trees to climate change reduction goals in the Bloomberg Climate Challenge and our own Strategic Energy Action Plan,” Phocas said.

Developers are often accused of being the driving force behind the removal of trees and clear-cutting tracts — but some say the city, and businesses, need to recognize the value of tees and preserve them.

David Furman’s work in Charlotte has mostly included high-density, urban developments, where saving trees often isn’t possible due to small sites and expensive land. But he said the Square, a new joint venture with Beacon Partners that includes offices, retail and apartments at South Tryon Street and West Boulevard, is a different case.

The development — including a 10-story office building and apartments wrapped around a parking deck — was planned around a “magnificent,” mature oak tree, Furman said. The site plan was developed around the tree, which is between the two buildings, and construction crews have put extensive measures in place to ensure the tree survives, Furman said.

The result: the tree is listed as an amenity (“signature tree”) on the marketing materials, and will provide shade for office workers, diners and apartment dwellers in the plaza between the buildings for years to come.

“Trees are great. And it takes a long time to grow one,” said Furman. “Canopies like Queens Road West are a source of communal pride, and are certainly worth planning and preserving.”

Shrinking Tree Cover in Neighborhoods

Many of the neighborhoods hardest hit by canopy loss are those most notable for their trees. These include Myers Park, Dilworth, Eastover, and Chantilly, all of which experienced double-digit percentage losses since 2012.

Data and analyses: University of Vermont Spatial Analysis Lab. Meta-analyses: Center for Applied GIS at UNC Charlotte

The picture is more complex than simply trees being cut down to make way for a city’s explosive growth, Cole said. Although large clear-cuts and storm-downed trees are most visible, the data shows individual homeowners removing trees on residential lots are the biggest driving force.

And Cole said he’s concerned that the trees which appear to be suffering the greatest losses are mid-sized trees, in the 30-60 foot range — not just the city’s great and majestic trees which draw the most attention.

“It’s not the really big ones,” he said. “But we’re losing ones that we would be dependent on to replace those.”

In Elizabeth, a neighborhood that has lost 14% percent of its mature canopy trees, Kris Solow has seen a lot of change, including the loss of dozens of trees on the former Martha Washington Apartments site being redeveloped by Pulte Homes.

“The city used to be able to get things done. After Charlotte lost 80,000 trees in Hurricane Hugo, there was a huge replanting effort. The Elizabeth Community Association received matching grants from the City, and we replanted more than 400 just in our neighborhood.”

Cole said he hopes to see more education efforts about the concrete benefits of trees, such as something which would allow people to see how much hotter the city would be without their shade, or how much worse flooding would be after a rainfall if trees were removed.

“We need to have an education plan out there to get people to understand why we need trees,” he said. “It’s not about raking leaves or not raking leaves.”

Reflecting on the challenges in reaching “50 by 50,” Solow recalled an old proverb: “The best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago. The next best time is now.”

Douglas A. Shoemaker, Ph. D. in Forestry and Environmental Resources, is Director of Research and Outreach at the UNC Charlotte Center for Applied GIScience. He studies pressing global resource and sustainability dilemmas. Ely Portillo is Assistant Director of Outreach and Strategic Partnerships at the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute.

Doug Shoemaker