Charlotte’s new focus on regionalism in transit brings more people to the table, but can they all agree on a vision?

If all the pieces fall into place, some day in the future a new light rail train will pull out of the station at the Central Piedmont Community College Levine Campus in Matthews and head south into Union County.

It will turn down a two-lane country road lined with pine trees; run alongside U.S. 74, where there’s a stop at the Atrium Health Union West hospital in Stallings; then pull into the end of the line by the Carolina Courts basketball gym and Indian Trail’s stately town hall.

That’s the vision, anyway, for the southernmost end of the proposed Lynx Silver Line. It’s estimated to be at least 15 years away. But the route to getting that 29-mile line built is likely to be choppier than a smooth ride on a shiny new light rail car.

At the moment, Charlotte’s transit plan is in a holding pattern. There’s widespread agreement on the need to plan for the future of our fast-growing region and to provide alternatives to cars. But many of the specifics remain fuzzy, especially how to pay for the estimated $13.5 billion, which would include a 29-mile, east-west light rail, rail to north Mecklenburg, more buses, expanded trails, greenways, sidewalks and bicycle infrastructure in Mecklenburg County, and some road improvements.

Charlotte leaders say they want to take time to work with colleagues from surrounding counties, to ensure it’s truly a regional plan — for reasons that are probably part sensible (we’re a connected region with shared challenges) and part political (Charlotte by itself might not be able to get what it wants from the General Assembly).

Like Mom and apple pie, regionalism is something everyone says they love. However, it also introduces more players into a process that’s already crowded with people with different ideas and interests.

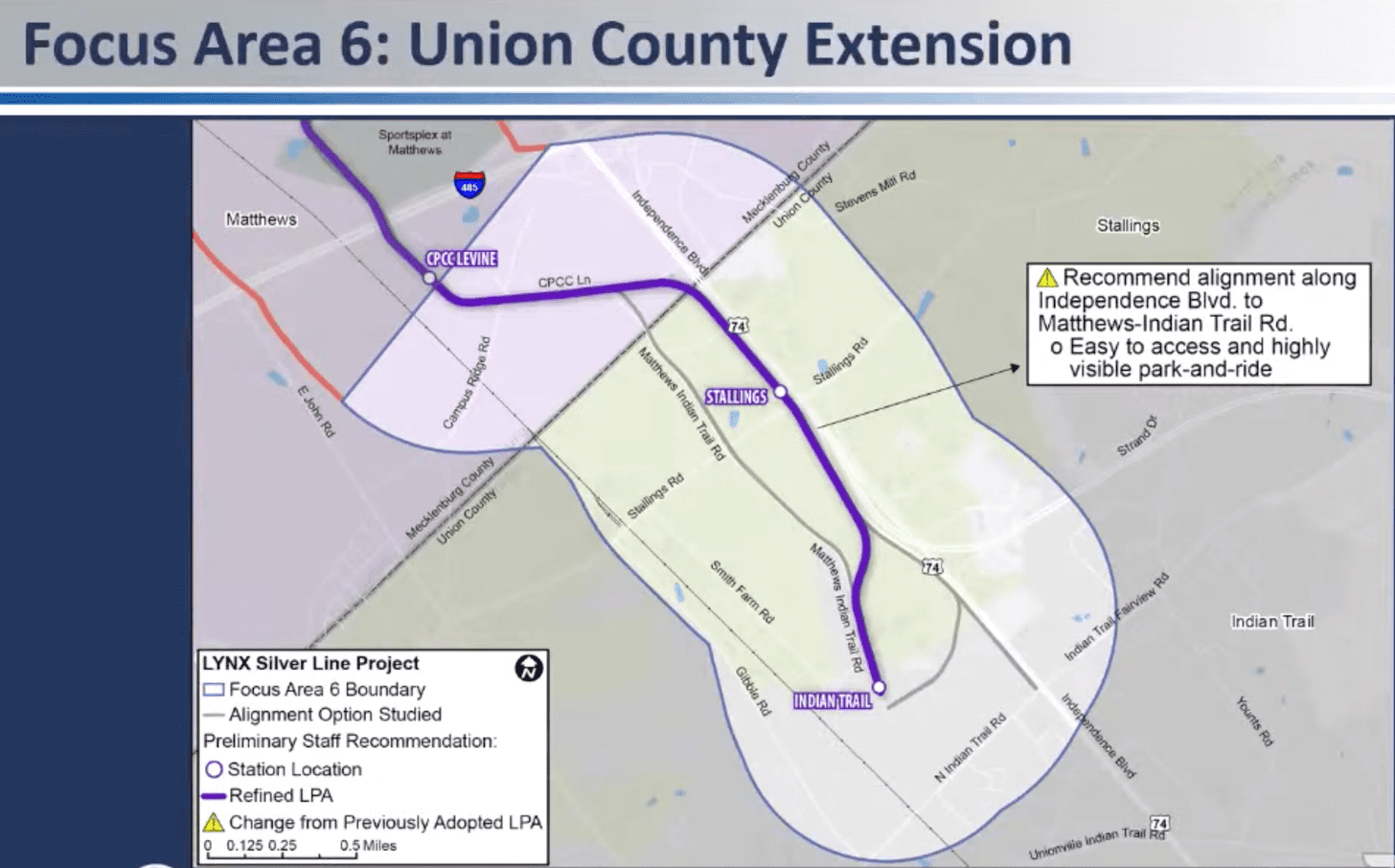

The latest proposed route of the Silver Line in Union County has it going from Central Piedmont Community College’s Levine Campus in Matthews to U.S. 74 in Stallings and south into Indian Trail.

The latest proposed route of the Silver Line in Union County has it going from Central Piedmont Community College’s Levine Campus in Matthews to U.S. 74 in Stallings and south into Indian Trail.

Take Indian Trail, the town of 40,000 just outside of I-485 in Union County. It’s not like everyone in town is clamoring to link to Charlotte’ light rail line and is willing to bear any cost to make it happen. Instead, residents have different opinions. In interviews this week, many said they liked the idea but want more information.

The town’s mayor, Michael Alvarez — who serves on the multi-county Charlotte Regional Transportation Planning Organization — says he’s not sure the Silver Line should extend all the way to Indian Trail. He says it could make more sense for the line to end in Stallings, by the hospital, where there’s room for park-n-ride lots.

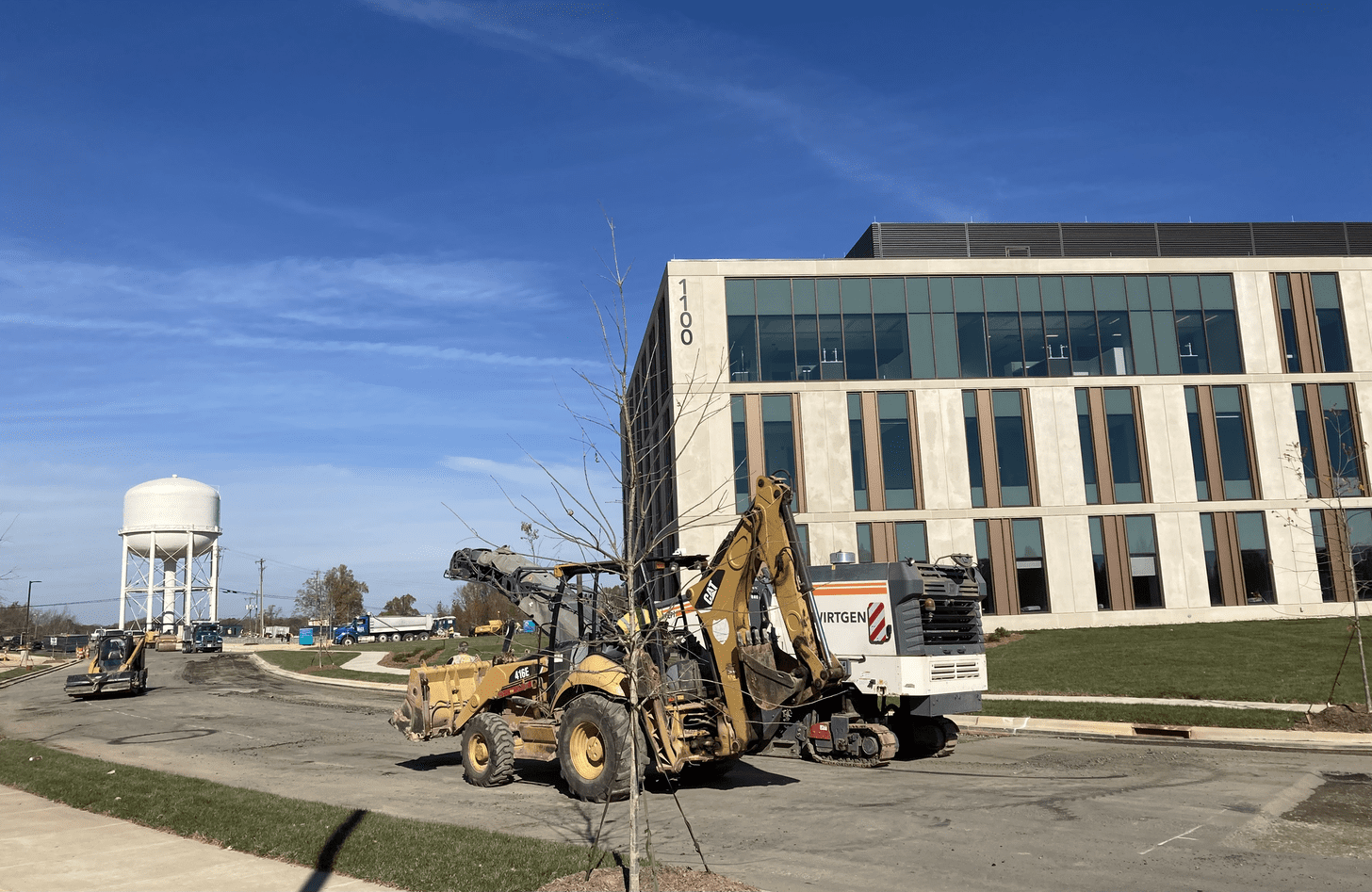

Atrium Health is building a new hospital in Stallings that could have a future light rail stop. Tony Mecia

“We just don’t have that many people,” he said. “And where would everyone park? There’s no room for it.”

He says something needs to be done, and he has no problem working with Charlotte on a transit plan. But so far, he says, there just aren’t enough details.

“I don’t see any really solid plans as of yet,” he said. “All I hear is, ‘How do I get this? Let’s tax.’ … I really don’t have much comment on it until they have a really solid plan, or solid plans of action — this is how much it’s going to cost, here’s what it will be in the future, here are the positives and the negatives and every aspect of how we would fund it and maintain it.”

Planners designing the Silver Line said at an online meeting earlier this year focused on the Union County portion that they have preliminary routes for the light rail but that answers to other key questions, including cost and ridership, have yet to be determined.

The latest recommendations on the Silver Line call for it to end in Matthews, though Charlotte planners are open to continuing to work on extending it into Union County as part of initial construction or a future phase. Andrew Mock, the Lynx Silver Line project manager, said at an October meeting that adding portions in Union or Gaston county “will require those regional funding requirements.” That probably means that Charlotte planners are unwilling to move forward with the Silver Line beyond county lines without outside sources of money to help pay for those portions. Mock said discussions with those counties are ongoing.

Lots of planning, but fragmented governance

In the Charlotte area, regional cooperation gets plenty of lip service. But actual regional governance structures remain fragmented or non-existent.

The Charlotte Area Transit System has a governing board, the Metropolitan Transit Council, with some regional representation, but all the voting members are from Mecklenburg County. CATS’ chief executive reports to Charlotte’s city manager, and the agency’s operating budget comes largely from Mecklenburg’s half-cent sales tax.

Other regional planning organizations — like the Charlotte Regional Transportation Planning Organization, the Gaston-Cleveland-Lincoln Metropolitan Planning Organization, the Cabarrus Rowan Metropolitan Planning Organization and the Rock Hill-Fort Mill Area Transportation Study — all make their own plans and pursue their own projects. (CRTPO, GCLMPO, CRMPO and RFATS — simple, right?)

And that’s on top of the dozens of municipalities, ranging from small, rural towns to major cities, working up their own plans. The state line throws another wrench in the regionalism works and makes funding questions for some projects more complicated.

And yet, regional plans are only likely to become more important as the region grows. Pre-pandemic, about half of Mecklenburg County’s workers commuted across county lines. A look south at Atlanta, a famously Balkanized, traffic-choked metropolitan area that nonetheless has a booming economy and coveted “world-class” status, makes Charlotte region leaders both nervous and jealous.

The Centralina Regional Council has been leading a planning effort covering 12 counties in the Charlotte region, called “Connect Beyond,” in parallel with Charlotte’s own plan. The regional blueprint calls for an expanded bus system, interoperable transit fares and combined scheduling. But it leaves open the question of who would pay for a regional bus system, and who would run it.

A growing area

People around Indian Trail this week don’t have a lot of answers, either. But in several conversations, they said the area is growing, it’s becoming more connected to Charlotte and traffic is getting worse.

Angela Simpson, owner of Indian Trail bakery Cake Affect, says more public transit would be a good idea to connect the growing area to Charlotte.

“Indian Trail is booming,” she says. “It’s starting to really boom with businesses and recognition. People are knowing that we are actually here.”

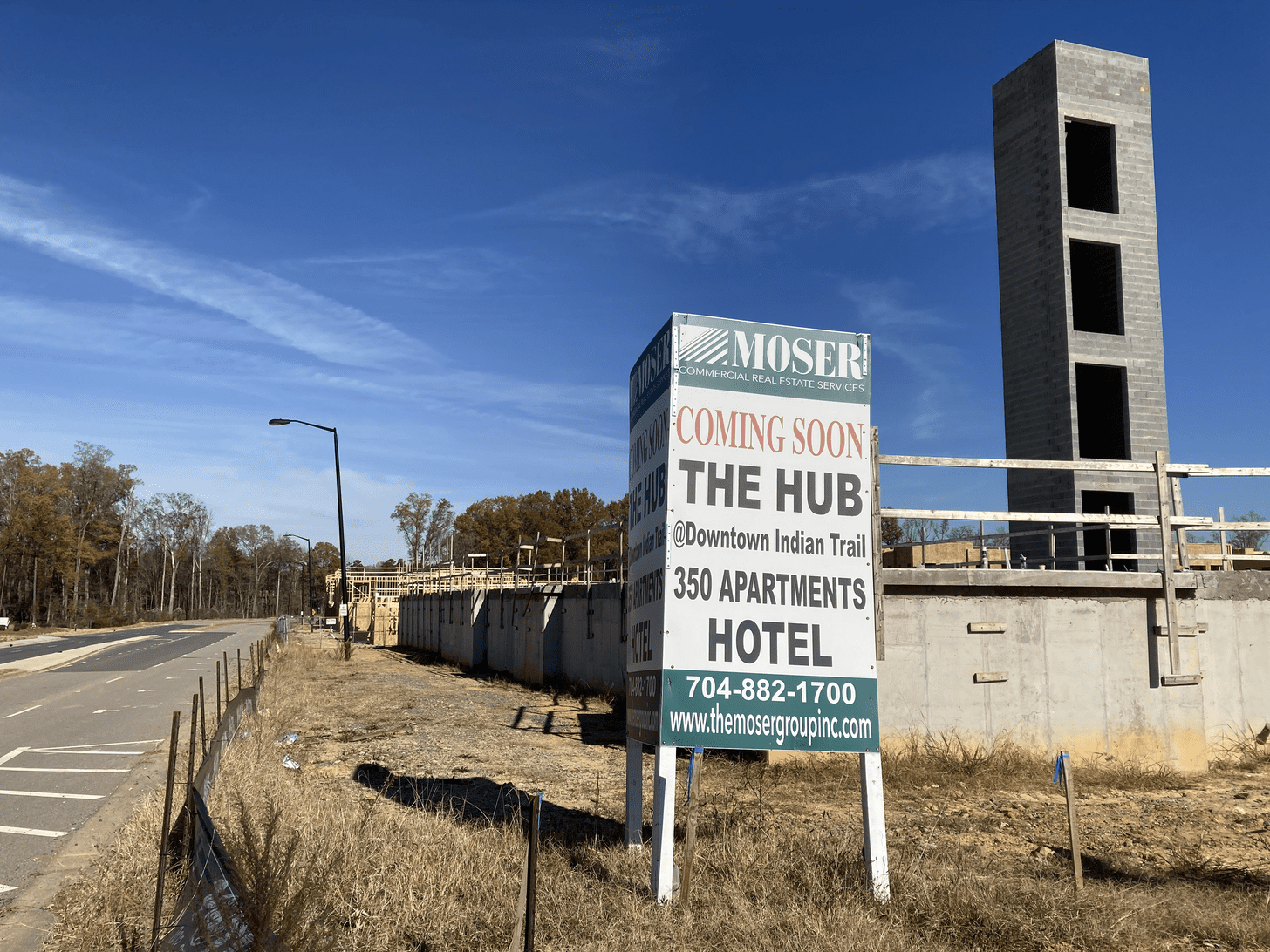

High-density gateway: The Moser Group Inc. is building 350 apartments and has plans for a 105-room hotel in a development called The Hub at Downtown Indian Trail. The developer says on its website: “The is the new gateway to Indian Trail.” Tony Mecia

A group of elderly men leaving Johnny K’s Restaurant at lunchtime on Tuesday were more ambivalent.

“My thought on it is, I’m too old for light rail,” said one of them, who didn’t want to give his name. “The way the traffic is, light rail might help a little bit. I don’t think it’s going to be here in time for me.”

This story was originally published in the Transit Time newsletter, a collaboration of UNC Charlotte’s Urban Institute, the Charlotte Ledger and WFAE.

Tony Mecia