Charlotte’s parking deck identity crisis: Can a deck be ‘green’?

There are three things most Charlotteans seem to agree on: a victory streak for the Panthers, a cool brew at a neighborhood brewpub, and free (or mostly free) parking. But with the surge of new and promising technologies and platforms in recent years – Uber, Lyft, autonomous cars, dockless bike sharing, and even electric scooters – the universe of urban travel has been thrown into an unprecedented state of flux. Even the fundamental notion of a parking deck is now subject to increased scrutiny, and for a host of valid reasons. There is more and more concern that the parking deck, like an annoying body rash, isn’t just a blemish, but more like a contagion.

In Charlotte, like other U.S. cities, developers worry because decks keep getting more expensive to build. In developer Clay Grubb’s provocative op-ed piece for the Charlotte Observer, he put the dollar amount at a whopping 20 percent of the total construction cost. But he would probably be the first to admit that building smaller decks or eliminating them altogether, at least in the short run, will meet resistance not just from consumers but also from conservative lending officers of banks that finance his projects.

Meanwhile mammoth decks, some with more than 1,000 parking spaces, get built even in the highest-density and most-walkable zones of Charlotte – places where walking and biking and transit are more readily available. In those areas, the other forms of travel should be the consumers’ choice, but that’s just not happening yet.

The Charlotte planning staff worries about parking decks’ impact on place-making. They know decks hog a lot of valuable urban real estate that could be going to higher and better uses, especially mixed uses where housing, shopping, workplaces and civic ventures all near each other can enhance the streetscape. They understand how decks, especially stand-alone decks, which offer only parking without stores on the ground floor or residences around the exterior, can suck pedestrian life from sidewalks and create unsafe conflict zones at driveways. Planners envision that a decade or two from now a typical Charlotte household will willingly opt to own fewer cars, or even no cars at all, because people will have so many other dependable, safe and cost-effective transportation options. If car ownership plummets, in theory so should parking demand.

Uptown Charlotte parking deck named “The Green,” at North Brevard and East Sixth Street. Photo: Martin Zimmerman

Uptown Charlotte parking deck named “The Green,” at North Brevard and East Sixth Street. Photo: Martin Zimmerman

Environmentalists in Charlotte and elsewhere worry about air pollution and carbon emissions from auto exhaust. They vilify and deride so-called “green” parking decks, calling them oxymorons, echoing Lloyd Alter, a popular Toronto-based blogger for TreeHugger.com. He asks: “Can a parking garage ever be green? Hardly. When you build more parking, you get more cars; if you want people to get rid of cars, get rid of parking spaces.”

The U.S. Green Building Council is the go-to source for independent third-party certification via its Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program which certifies buildings based on a ranking of environmentally friendly techniques. USGBC disallowed green credits for parking decks in 2011, but they rebooted in 2016, partnering with “Parksmart,” a certification program administered by Green Business Certification Inc. You may or may not agree with this shortened version of Parksmart’s credo: “Parking structures can achieve reduced environmental impact, increased energy efficiency and lowered energy usage … such structures succeed at diversifying mobility options, promoting alternative modes of transportation and reducing operational costs up to 25 percent compared to the national average.”

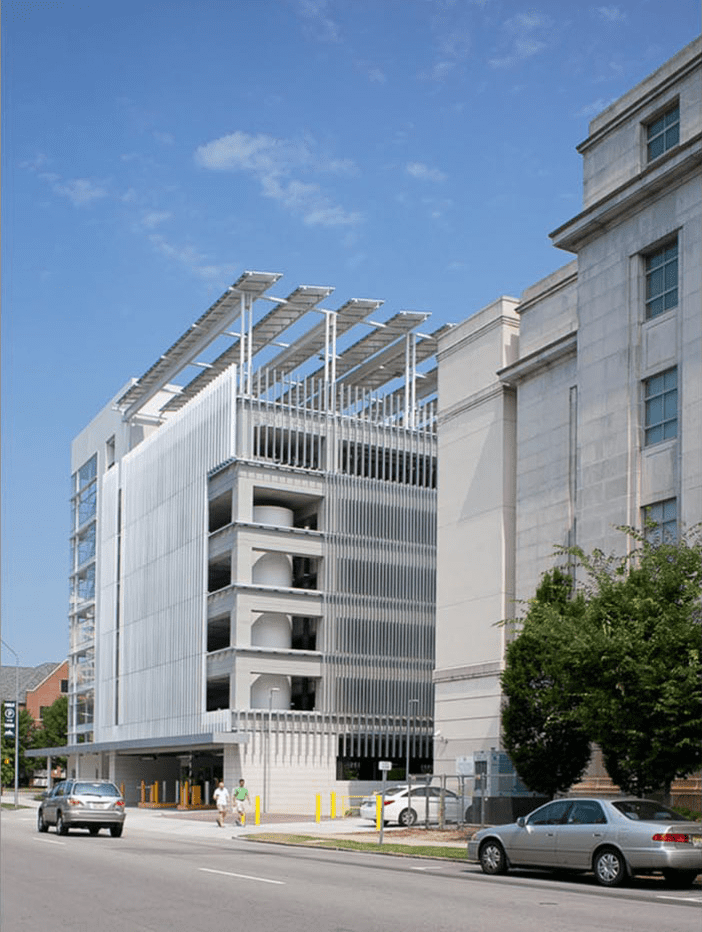

The Green Square parking deck in Raleigh. Photo courtesy of Jonathan Hillyer

The Green Square parking deck in Raleigh. Photo courtesy of Jonathan Hillyer

In Raleigh, the elegant Green Square parking structure illustrates the art of the possible when the will to be sustainable merges with a budget level that supports the added green features. Green Square is a state government-financed complex that includes a museum and an office building.

It uses several sustainable design strategies such as a façade of vertical aluminum fins, recycled and recyclable, and a large cistern that stores rainwater for irrigation at the State Capitol and neighboring state-owned grounds. A solar array of photovoltaic panels hovers above the entire top level of parking and doubles as a sunshade. Some of its energy goes directly to the office building; the leftover is sold to Duke Energy where it goes into the power grid. The third party that has supplied and installed the array receives reimbursement from Duke along with tax incentives. The result is enough energy to power 3,000 homes a year. On the downside, at 900 spaces, the structure occupies an entire city block, and none of its ground floor space is given to commercial tenants.

Charlotte has yet to see – from government or the private sector – a deck to match that level of sustainable design. The phalanx of new decks, designed by LS3P, at Charlotte Douglas International Airport has some green features, such as recycled fly ash and LED lighting, but airport management did not prioritize green design the way state officials did in Raleigh. For his part, Lloyd Alter would shriek if he knew Charlotte’s airport holds space for more than 30,000 cars. In rough terms, that amounts to a $150 million capital outlay, and possibly millions more if you add in the roads and utilities connecting to the parking.

Parking deck at Charlotte Douglas International Airport uses some “green” features such as LED lights and recycled fly ash. Photo: Martin Zimmerman

Parking deck at Charlotte Douglas International Airport uses some “green” features such as LED lights and recycled fly ash. Photo: Martin Zimmerman

For its part, Charlotte’s Planning, Design and Development Department seems poised to seize the moment. Last month, as part of a rollout for zoning reforms to transit-oriented districts (TODs), staff urban designer Monica Holmes recommended to an advisory committee a requirement that decks in the most intense TOD locations be designed as adaptive reuse structures. The committee – a healthy mix of architects, developers, private sector planners and citizen activists – serves as a sounding board for a new Unified Development Ordinance (UDO) that is expected to replace the antiquated city-wide zoning code.

The basic idea is to make sure floors are flat and ceiling heights are raised to allow conversion to civic, office, retail, housing or other uses in the future. That is easier said than done, because those and other necessary changes can add appreciably to construction costs. To date there are only a few instances where adaptive reuse decks have been built or are in the pipeline in other U.S. cities, most notably the decks planned for the Massachusetts Convention Center Authority in Boston.

Make no mistake. Parking decks are now being viewed through a different lens. Whether Charlotte decision-makers support adaptive reuse for parking decks in the new TOD zoning should be decided in the coming months, as the TOD sections of the city’s new development ordinance move forward for approval by the Charlotte City Council.

Martin Zimmerman of City Wise Studio USA is an urban planner, journalist and sustainable city activist who writes frequently for PlanCharlotte.org. Opinions in the article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.