Experts: SouthPark needs vision, stronger design and champions

Most of the ideas about SouthPark offered last week by a group of out-of-town development experts were what you’d hope to hear from 21st-century planners: create connections, try public-private partnerships, build a better public realm. But a few of their comments might raise questions or even baffle some Charlotteans.

The advisory panel from the nonprofit Urban Land Institute spent much of the third week in March studying the SouthPark neighborhood and talking to area residents, workers and business leaders. They presented their analysis and recommendations in a session Friday, March 17, at the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Government Center.

|

SouthPark numbers 14 million square feet – built space 5.5 million square feet – office space 3.2 million square feet – retail space 98 percent – retail occupancy rate 25,000 office jobs |

Their analysis noted that while SouthPark is an area with a mix of uses—residences, offices, stores and civic uses—it’s poorly connected, auto-oriented and has problems with traffic congestion. Getting from one part of the neighborhood to another can be tough for anyone who isn’t driving. It has few public gathering spots. And its future? As panel member Jordan Block of RNL Design in Denver put it, “SouthPark is at risk of becoming a mall-anchored suburban office district.”

SouthPark, in their view, needs:

- Greater connectivity

- More public places for people (as opposed to places for cars)

- Stronger urban design and development standards

- Public-private partnerships to help carry out the vision

- More infrastructure investment by the city

- A group to be a voice and champion for the area

(Keep in mind that these are only recommendations from an outside group, not official proposals from any city or county agency.)

They recommend the city:

- Create a detailed plan for how to shape the character of the public spaces. Remember that streets and sidewalks are public spaces, too. The ULI panel noted the most recent city plan for the area came 16 years ago, in 2000.

- Focus on developing public-private partnerships. This would help in developing more public parks and gathering spaces. For example, they noted Symphony Park is not publicly owned and isn’t well used except when events are planned there. They said the green spaces that do exist in the area are “ambiguous,” meaning it’s not clear if they’re public or private.

- Create lively programming. See above, about Symphony Park not being used much of the time.

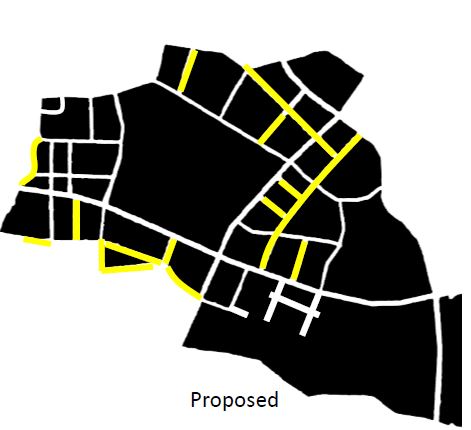

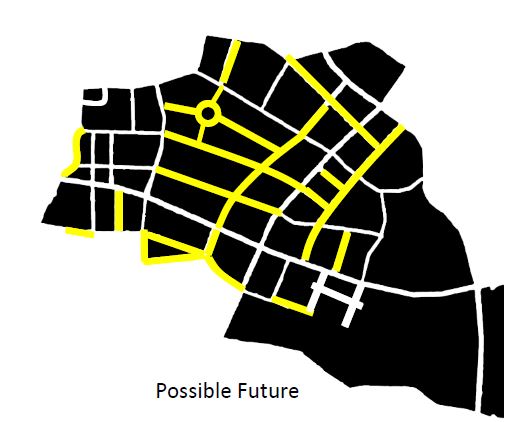

- Improve connectivity. Tame some of the traffic congestion by making it easier to move within the area, especially by foot, bicycle or transit. Add streets to ease congestion. Make safe bicycle routes and pedestrian amenities a priority and connect to the Cross Charlotte Trail which will be built beside little Sugar Creek, only about a mile from the mall. When filling in the street network, make block lengths shorter.

“The city and county have taken SouthPark for granted,” said Ed McMahon of the Washington-based ULI. “The city and county have simply assumed that SouthPark could take care of itself. And despite SouthPark’s importance to the economy of Charlotte, we believe that the city has underinvested in SouthPark, its public realm and its infrastructure. “

Whoa. The city has “underinvested in SouthPark”?

That may strike many as off-base. After all, SouthPark is one of the wealthiest parts of the city. The neighborhoods closest to and including the mall have a median household income of $107,387, according to the city-county Quality of Life Explorer. That’s almost double the countywide household median income of $56, 472. Plenty of less affluent Charlotte neighborhoods have needs the city should support. How can anyone justify putting city money into such a rich area?

But then I had to stop and think. Cities, after all, are complex systems, not simple linear formulas. Policy decisions usually don’t produce easy, formulaic results, and their effects don’t stay fenced into one geographic area. Something happening over here affects what happens over there, even if you didn’t expect it. Land uses, for example, affect transportation and vice versa. School decisions have ripple effects throughout the county. Jobs and spending aren’t limited by zip code.

Through that lens, it’s fairly clear that there’s a common good in improving infrastructure everywhere. With limited funding, city officials—like those in other cities—can sometimes seem to be treating

infrastructure improvements as gifts to be bestowed on the “deserving”—however one defines “deserving.” But true connectivity has to connect all parts of the city, rich as well as poor. As McMahon and others on the panel pointed out, most people who work in the SouthPark area don’t live there. Better transit access, bike lanes and connections in the SouthPark area will help plenty of people who aren’t the affluent neighbors.

Even if it means some city money is going to be spent in a wealthy area.

The other recommendation that may raise some eyebrows is the concept that adding streets will help with traffic. To a lot of people, “street” equals “traffic.” So if you want less congestion why would you want more streets, which means more traffic?

It sounds counterintuitive, but with more streets, motorists have more options for which route to take. That disperses the traffic onto more streets. Today, if you want to get from one side of the SouthPark are to the far side, you have only a few choices, and those main streets are typically congested. Adding more streets would mean fewer vehicles on the big, main streets.

The final head-scratcher for some folks is the emphasis on short blocks. What’s the point of that? One reason, McMahon said, is to encourage pedestrians: “The shorter the block the more people are likely to walk.”

But then he focused on an economic reason, and in a city so profoundly focused on business and real estate, it probably perked up some ears: “The most valuable real estate is always the real estate at the corners,” he said. “You just don’t have enough corners.”

Opinions in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

CLICK IMAGE TO DOWNLOAD SLIDE PRESENTATION

SEE THE ULI PRESENTATION ON VIDEO