‘Hate the bus lane.’ Drivers flooded Charlotte with opposition to pilot project

Just a couple of years ago, Charlotte Area Transit System planners were talking a lot about the potential for bus-only lanes to make the city’s buses faster and more reliable, giving them an edge over cars stuck in gridlock.

Charlotte debuted a blocks-long bus-only lane on Fourth Street. Then, the city marked off one lane each way for buses, bikes and emergency vehicles on part of Central Avenue, plied by the busy No. 9 route. CATS officials said they were examining other high-frequency routes where it might make sense to designate lanes for buses, as well as extending the Central Avenue bus-only lanes to uptown.

But by early 2021, the Central Avenue bus-only lane experiment ended after six months. Cars returned to all four lanes. The discussion about adding bus-only lanes subsided, and CATS officials shifted to talking more about technology that will give buses priority at traffic signals as a way to make the system more reliable for riders.

CATS recently released survey results about the Central Avenue experiment in response to a public records request, and they hint at why there’s been a shift — and at the hurdles Charlotte will have to overcome in seeking to restore its battered bus system and get drivers to opt for public transportation over their private cars.

CATS opened the bus-only lanes on Central Avenue in September 2020, using white paint to convert one out of the two lanes each way from general traffic to select vehicles only. While the pilot ran, until March 2021, CATS gathered feedback from bus riders, bicyclists and drivers.

We’ll get into more detail below, but the main upshot is this: While bus riders and bicyclists generally said they favored the new lanes — which saved them time and made bicyclists feel safer — drivers hated them. “Hate” might be too soft a word, in fact — “despise,” “revile,” “detest” and “abhor” all come to mind as well.

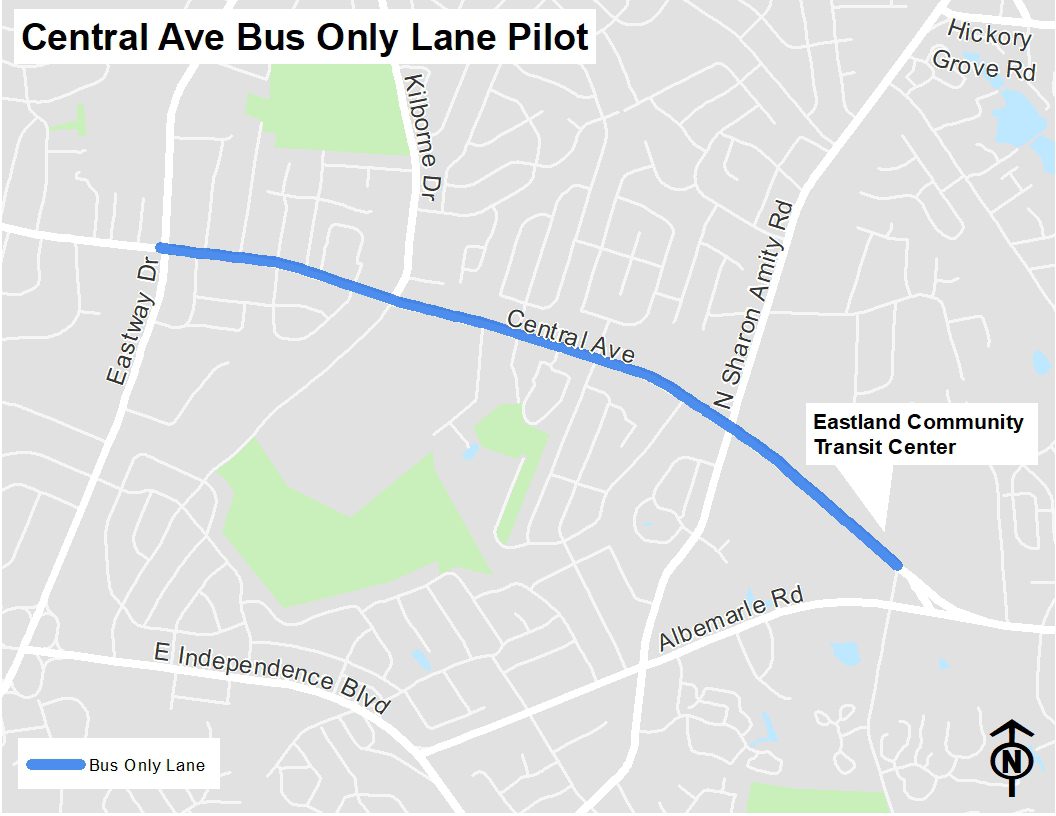

The Central Avenue bus-only pilot lanes. Map: City of Charlotte.

There’s nothing unexpected about that. If you want to see some local politics fireworks, just suggest taking away parking or reducing lanes for cars. But the CATS survey results highlight how big the disparity in public opinion was: CATS received survey responses from 797 drivers, compared to 69 bus riders and 43 bicyclists.

And while bus riders left CATS three additional comments in support of the bus-only lanes, the agency got more than 400 blistering comments from car drivers against the lanes.

“Dumb idea.”

“They are dangerous!”

“I hate the bus lane and will continue to drive in it. Nobody got time for that.”

“This is a disaster. Why confuse and constipate regular traffic 24 hrs a day for bikes and buses used mostly a few hours a day? Dumb.”

And so on.

These survey results might reflect anti-bus bias, a knee-jerk reaction from car drivers, genuine frustration with longer drive times or a disparity in political and social power (for example, low-income bus riders might be less likely to take an online survey than higher-income drivers who get a link to it on the neighborhood listserv).

They might also simply represent the greater number of drivers: Central Avenue carries up to 29,000 vehicles per day, while the No. 9 route averages somewhere in the neighborhood of 1,725 riders (not accounting for weekday and weekend fluctuations). But whatever the underlying factors are, it’s clear what they represent for CATS’ push to fix its bus system: A problem.

And while we’ve mostly been talking about where to get the actual capital to pay for Charlotte’s $13.5 billion transit plan, these survey results highlight that perhaps we should be talking more about the political capital needed to force big changes on an auto-dependent, “New South” city.

The survey

So why write about this survey now, a year and a half after the bus-only pilot ended? Well, Transit Time requested the survey results in March 2021, but we received them only last month. We play the cards we’re dealt.

The case for bus-only lanes is pretty simple. Buses can move more people than individual cars in the same amount of space. Just picture a bus with 35 riders vs. 35 separate SUVs. But if those buses are stuck in the same traffic as everyone else and there’s no time savings to ride the bus, luring drivers out of their cars will always be a challenge. That’s even more true in a sprawling city like Charlotte, where transit officials have long highlighted the system’s infrequent buses and 90-minute average one-way travel times as serious problems.

Charlotte’s bus system has been losing riders since before the COVID-19 pandemic, and over the past few years has seen ridership decline by about 75%. More buses, officials say, are only part of the solution.

“We continue to invest in more frequent service, but that being said, if we put more vehicles on the street and more frequent service and they’re still stuck in the same congestion that everyone else is, we would have fallen short of the mark,” CATS chief executive John Lewis said at an April meeting of the Metropolitan Transit Commission.

[Read more: ‘Better buses. Better cities.’]

Enter bus-only lanes. Central Avenue would seem to be a logical choice: The No. 9 bus is a high-frequency route with the highest ridership in the system, and Central Avenue connects uptown to diverse east Charlotte neighborhoods and the transit hub at the former Eastland Mall site.

“Data gained from the pilot and survey will help to identify opportunities to implement similar pilot programs in other bus corridors throughout Charlotte,” CATS said when the lanes opened.

Those survey results were clear. Of the bus riders, 56% said their commute was somewhat or extremely improved and 68% said they would be more likely to ride the bus if Charlotte installed more bus-only lanes throughout the city. Bicyclists were similarly enthusiastic about the lane, which gave them a full lane to buffer them instead of being squeezed by traffic.

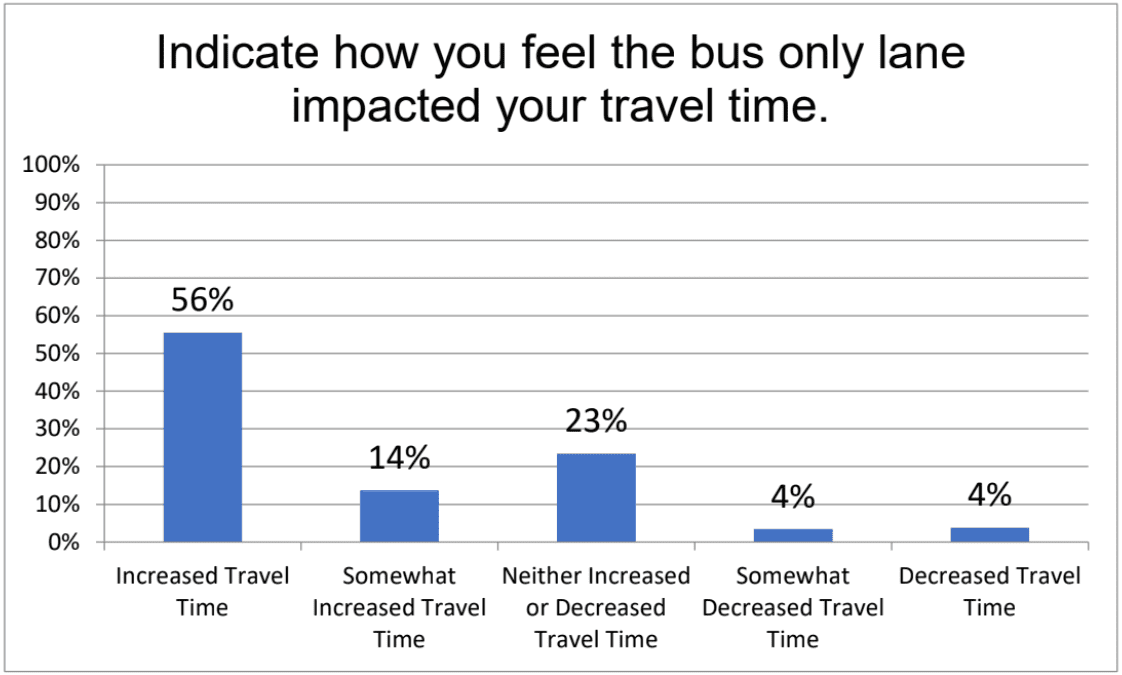

For car drivers, it was almost the exact opposite story. A withering 70% said the bus-only lanes increased their travel time, while 73% said they were extremely or somewhat unlikely to use transit more if there were more bus lanes (10% said they were neither more or less likely to do so). And 83% of drivers said they rarely use transit (“never” wasn’t an option).

And nearly 12 times as many car drivers responded to the survey as bus riders.

Car drivers felt strongly that the bus-only lanes slowed them down. Chart: City of Charlotte.

Bus-only lanes on the city’s busiest corridors might well be a good idea from the standpoint of making transit more efficient and reliable, bringing down transit times and giving people a reason to step out of their car and onto the bus (and if Charlotte is going to have a chance at reaching its goal of shifting half of our automobile trips to something besides a car by 2040, they’ll have to give people a pretty good reason). But it’s clear that the Central Avenue bus lanes were a tough sell (or more bluntly, a toxic idea) in Charlotte.

More modest measures, like giving buses the ability to jump to the front of the line at red lights and letting buses run in toll lanes on I-77 and Independence Boulevard, are likely to be less controversial. And that’s where CATS is focused, for now.

John Holmes, co-founder of Charlotte Urbanists and an advocate for transit and bicycling, said that if Charlotte pushes bus lanes again, he hopes the city will focus on other benefits besides just those to buses, such as the ability for EMS to glide past traffic during rush hour and the potential for permanent bus rapid transit corridors to spur more transit-oriented development.

Bus-only lanes, Holmes said, could be portrayed as a faster and cheaper alternative to get the traffic-circumventing and development-spurring benefits of more light rail and streetcars that remain decades away and unfunded.

“You can have that right now with paint and a bus that runs every 10 minutes,” said Holmes.

This story was originally published as part of the Transit Time newsletter, a collaboration between WFAE, the Charlotte Ledger and the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute.