Here’s what the next 20 years could hold for uptown Charlotte

A new “Central Park” for Charlotte. A Tryon Street that prioritizes pedestrians over cars. A new neighborhood built around the Carolina Panthers’ stadium, and the burial — or even total elimination — of I-277.

These are some of the big ideas planners are batting around as they work on the new Center City Vision Plan, meant to guide development in uptown and the surrounding neighborhoods for the next two decades. Charlotte Center City Partners is leading the effort, in collaboration with consultants and local governments.

The groups were originally supposed to have draft recommendations this spring and a final plan this fall. Center City Partners CEO Michael Smith told city council’s Transportation, Planning & Environment Committee this week that they’ve slowed down the process in light of the coronavirus pandemic and protests for racial justice.

“We decided to take a step back, regroup and reflect,” said Smith. “Now, with fresh eyes, we can challenge our preconceptions…The plan will be informed by our new reality.”

The timeline now calls for more community outreach and engagement (much of it virtual, given the pandemic), with a draft plan this fall and a final plan sometime in the winter.

Charlotte’s history of planning for its center city goes back decades, to the Odell Plan in 1966 (when it was still called downtown). The grand plans for center city have been revised by local boosters more or less every decade since. Though they are non-binding, the plans tend to be very influential. Much of what’s in them has come to pass (a baseball stadium, First and Third ward parks, a redeveloped Stonewall Street) while other suggestions remain aspirational (capping I-277, loops of protected bicycle lanes, Charlotte’s version of the St. Louis Gateway Arch).

[Read more: Charlotte is planning a new vision for center city. How’d we do on the last one?]

Even though Center City Partners hasn’t formally released its 2040 plan recommendations, there’s enough information posted online and in Monday’s city council presentation to get a good sense of where they’re going, though it remains light on details. Here are some key areas where the plan will focus — and where it might change the course of Charlotte’s growth:

Getting rid of I-277

It’s an idea that’s been in previous plans without coming to fruition, but somehow ridding uptown of the 277 loop remains popular — at least on paper.

“What does center city look like with 277 either removed or completely converted?” asked council member Larken Egleston, who called the small loop highway a “wound.”

“I don’t know anybody who’s a big fan of it now,” he said.

As a road, I-277’s main purpose is to funnel people around uptown and take them from one highway to another. It cuts off much of the central city, functioning as a barricade. Plans are underway for a new pedestrian bridge to help connect South End to uptown across the open trench of traffic, but it will still remain a moat of cars.

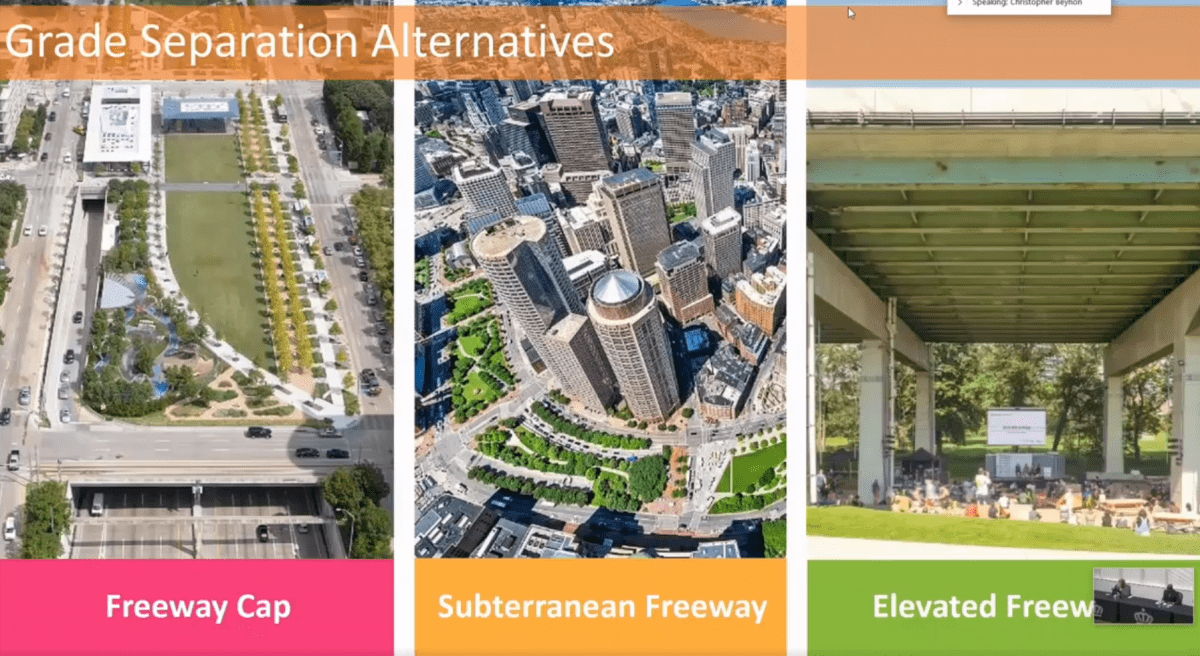

Ideas for changing I-277, presented to Charlotte City Council via Zoom.

Smith said ideas for changing 277 that “push the limits” will be considered. Those could include building a “cap” over part of the highway that could then serve as a park, or one day eliminating it completely and restoring something like the grid system that once connected neighborhoods around uptown to the center city.

“This infrastructure has been a divide for a long time,” said Chris Beynon, one of the consultants with MIG working on the plan.

Balancing parking needs

“The days of building cities for cars only are behind us,” Smith said. He and urban planners are looking to a future where more people bike, ride transit or walk to work from denser, mixed-use neighborhoods.

But that vision might be harder to achieve in practice: More than eight in 10 Charlotteans still drive to work along, and a slight majority of workers in Mecklenburg County commute from other counties (almost all by car). And most new uptown developments have included massive parking decks even when they’re only blocks away from — or adjacent to — light rail stops, like the Legacy Union development at the former Charlotte Observer site or the Whole Foods and apartment building at Stonewall Station.

“That’s a very pointed conversation right now that we’ve got to have,” said Mayor Pro Tem Julie Eiselt, especially as many of the remaining surface lots in uptown are developed. “What’s going to be the growth of parking garages uptown? How is that balanced?”

Building around the stadium

With the Panthers likely to push for a new stadium sometime in the next couple of decades, Center City Partners is planning for development around it. Beynon pointed to CenturyLink Field in Seattle and U.S. Bank Stadium in Minneapolis as models: Stadiums in the middle of densely built neighborhoods, with adjoining retail, bars and apartments, along transit lines.

In Charlotte, the planned Silver Line light rail route runs adjacent to the stadium site, and neighborhoods to the west are already seeing rapid redevelopment.

Medical school opportunities

The vision plan will extend beyond uptown, encompassing roughly a two-mile radius. Dilworth falls into that area, and that’s where Atrium Health recently won a rezoning that will allow expansion of its main campus and the addition of a medical school.

Atrium and Wake Forest announced last year that they plan to build a medical school in Charlotte, though they haven’t officially said where yet. One focus of the new plan will be leveraging a new campus in Dilworth and connecting it to uptown. Though the details remain scant, this is one area that could clearly be transformative for a big part of the city.

Tryon Street reimagined

Tryon Street is Charlotte’s Main Street, arguably the densest hub of pedestrian activity. But retail (besides food and beverages) remains scarce, and the sidewalks are often crowded on a streetscape that still sees more space given over to cars, with limited seating opportunities and little outdoor dining.

The vision plan will call for reworking Tryon Street with more “activated” building ground floors (think storefronts), outdoor seating, small shops and cafes, public art and spaces for people to gather.

A “signature public space”

Uptown Charlotte has four main parks, one in each ward, but none of them are really big enough to be a main park for the city (parks that might fit the bill, like Freedom Park, are outside uptown). That’s something planners hope to change.

“Do we have that true ‘Central Park’?” Beynon asked, rhetorically. “Do we have a place we can gather for those big types of events?”

The vision plan is zeroing in on the area around 11th and Tryon streets, where the Blue and Silver light rail lines are expected to intersect. That hub (though it’s been criticized for being on the edge of center city) could serve as a bridge across I-277 in the north and incorporate the signature public space with “iconic art” that the city has long sought.