How fast is Charlotte losing its tree canopy? No one knows

Charlotte’s losing three football fields a day worth of trees – or, at least, we were from 2012 to 2018. But after four more years of a torrid building boom, no one can say with any certainty whether that loss has accelerated, slowed down or remains unchanged.

The city of Charlotte hopes to soon begin work on an updated tree canopy analysis, to figure out how tree coverage is changing now and what’s driving it. The last analysis was completed with data from 2018. That study found Charlotte’s tree canopy coverage fell from 49% of the city to 45% of the city in six years.

In response to those losses, the city is planning to implement its first-ever rules requiring homeowners to obtain a permit to remove large, native trees, as well as tougher requirements for developers to replace large trees that are cut down.

But the canopy study itself hasn’t been updated since 2018.

“It doesn’t feel like these numbers are realistic, based on the explosive growth we all know we’re undergoing,” said council member Renee Johnson, at City Council’s Environment, Engagement & Equity Committee meeting on Monday. “We’re not being realistic and we’re not being effective by looking at this city with 2018 numbers.”

[From 2018: Charlotte’s losing its green canopy, despite efforts to save trees]

Tim Porter, Charlotte’s urban forester, said it will take three to six months to do a new canopy analysis if data is available, and up to a year or more if the city has to collect new data. The data collection for such studies involve flying a plane (typically by the state or federal government) over the entire city and measuring billions of data points with LIDAR, as well as collecting new aerial imagery. Once the data is in hand, staff would then analyze the changes and recommend updates to the city’s canopy goals and tree regulations in 18 to 24 months, Porter said.

That timeline struck some of the committee members as too long. They wondered how they’re supposed to know if the tree regulations they’re enacting in the city’s new Unified Development Ordinance — set for approval next month — are effective or far-reaching enough.

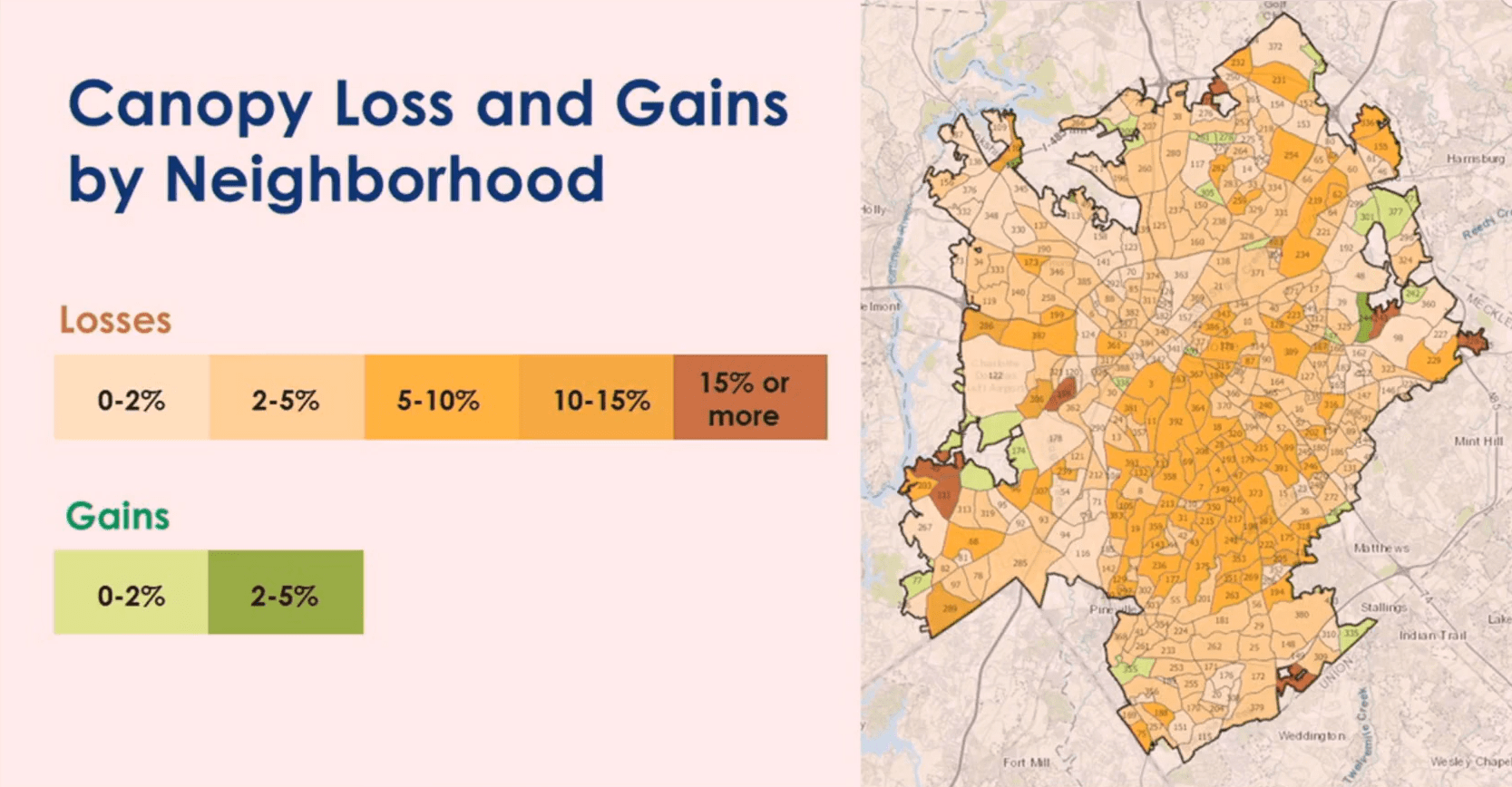

A slide detailing tree canopy loss in Charlotte by neighborhood. City of Charlotte.

“It’s very concerning,” said committee chair Dimple Ajmera.

City staff members said they will be able to propose updated regulations once a new canopy analysis is complete, and council can amend the ordinance later as needed.

Widespread decline

Charlotte remains a well-forested city compared to many of its peers. A 2018 study estimated that 39.4% of all urban land in the U.S. has tree cover.

“Charlotte has a robust tree canopy, still,” said Porter. “But there is significant decline, and that can’t be ignored…It’s a widespread, citywide trend of canopy loss.

Porter said Charlotte is at a “crossroads moment” as growth continues – both denser, infill development in existing neighborhoods and outlying, greenfield development around Charlotte’s edges.

While Porter said he’s sure the trend of tree canopy loss is continuing, there are other questions the city doesn’t have a good answer for besides the simple inquiry of “how much are we losing?” For example, the 2018 study found that the biggest source of tree canopy loss in Charlotte is individual trees removed on existing single-family lots, not clear-cutting for big, new developments.

“This is an area that was eye-opening and surprising to us,” said Porter. But the city doesn’t have a good grasp of exactly what’s driving that loss. Is storm damage as significant a driver as infill development (such as someone cutting down trees to build two houses on a lot where there was previously one)? Are single-family lots still the biggest source of tree loss, or are new developments around the I-485 outer belt shifting that?

A formerly wooded lot in south Charlotte with trees cut for a new single-family house. Photo: Ely Portillo

Once the city has some of those answers, Porter said they’ll be able to adjust their goals for the tree canopy’s future. Charlotte’s current goal of “50 by 50” was adopted in 2011, and refers to the aim of reaching 50% tree canopy coverage by 2050. With canopy coverage continuing to decline rapidly, that’s not going to happen.

Porter said the 50 by 50 goal – while catchy – didn’t take into account some of the nuances, like equity (is the tree canopy concentrated in wealthier neighborhoods?), the environmental value of trees for reducing air pollution and stormwater runoff, what kinds of species are best, and the temperature-lowering abilities of trees in a warming world.

Whatever goals Charlotte sets, Johnson said getting updated data quickly will be critical.

“Looking at 2018 – that’s like trying to solve a problem for another city. We’re not the city we were in 2018,” Johnson said.