The landscape of advanced classes in CMS

As Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools strives to meet the needs of all 141,171 students, part of its charge is to ensure that all students are ready for either careers or college. Of the almost 40,000 CMS high school students, how many will graduate ready for college?

AP as a measure of college readiness

CMS has clearly stated its goal to “accelerate academic achievement for every child and close achievement gaps so all students graduate from CMS college- or career-ready.” [1] With the district’s focus on increasing college-readiness, it is helpful to understand the landscape of student enrollment and course offerings in the Advanced Placement (AP) program. The College Board [2], a national, nonprofit educational group, administers and oversees the AP program, which is designed to promote a rigorous academic curriculum that meets the standards of college-level coursework. Students have the opportunity to take AP exams, which sometimes can be used for upper-level course placement in college and/or college credit [2] [3]. Taking AP courses and doing well on AP exams can be prerequisites to win admission to highly selective colleges and universities.

One point of discussion surrounding the AP program concerns equity, access and the achievement of underrepresented and marginalized groups of students. It has been extensively documented that grave disparities exist nationwide in AP course access between upper/middle income communities, and low-income communities, which largely serve students of color [4] [5] [6] [7]. There are three categories of explanation for the racial/socioeconomic disparities in AP enrollment: pre-high school disparity, offering disparity, and across-school access disparity [5].

- Pre-high school disparity. Students with relatively low advanced course-taking rates (minority, poor, male) begin high school much less prepared than other students because of their educational needs, family backgrounds, neighborhood characteristics or the quality of the education they receive in primary school.

- Offering disparity. Students attend schools where advance courses are not offered.

- Across-school access disparity. Students with low course-taking rates attend high schools with characteristics that lower their likelihood of enrolling in advanced courses even when they are offered.

Other barriers that have been noted are small school size, lack of teachers certified to teach AP courses and the high costs associated with AP programs [8]. CMS is in an interesting position as an urban district serving both high wealth and low wealth communities. What picture emerges from CMS when we look at equity, access and achievement in advanced classes?

Demographics of CMS AP student enrollment

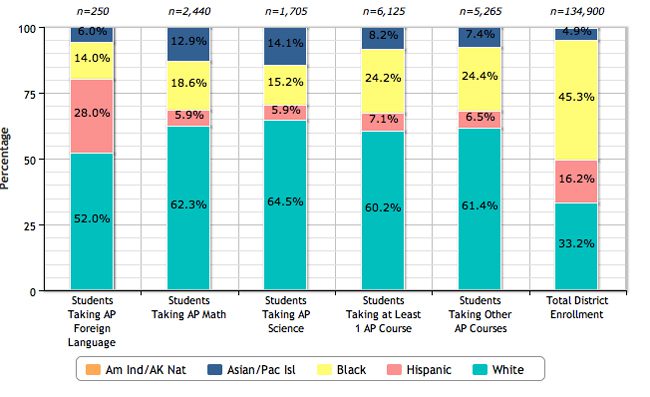

At CMS, like many other urban districts across the country, students at schools in low-wealth areas are likely to be inadequately prepared for college success [9]. The chart below gives an overview of the 2009 CMS AP enrollment by student racial demographics. The bar on the right side of the chart shows the district’s overall demographics. They are used here to show the comparison of AP racial demographics by subject to CMS’ overall racial demographics. African-American students make up 45.3 percent of total CMS student population but represent only 24.2 percent (1,531) of students taking at least one AP course. By contrast, white students make up 33.2 percent of CMS total student population and 60.2 percent (3,675) of the students who take at least one AP course. The difference between racial groups is even more pronounced in AP math and science classes. In those subject areas, African-American and Hispanic students are under-represented compared to their numbers in the total district population.

2009 CMS AP enrollment by AP subject and race

Source: U.S. Department of Education 2009-10 Civil Rights Data Collection

Notes: Columns may not add up to 100 percent due to rounding errors. Does not take into consideration the number of students eligible to take AP courses during 2009 (high school students); the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights provided only the total district enrollment. 2009 data are the most recent available. 2012 data will be released in fall 2013.

CMS AP course offerings

The map below shows the total enrollment and number of AP subjects offered at each CMS high school in 2009. It should be noted that Performance Learning Center (PLC), Turning Point, Hawthorne, Midwood and Metro are alternative schools and have small enrollments as well as a transient student body. As mentioned above, there are several possible explanations and rationales for student enrollment and subject offerings in the Advanced Placement (AP) program. Our analysis focuses on the racial and socioeconomic factors as they relate to equity and access in the district. With African-Americans representing the largest racial group served in CMS schools, the second map (click tab African-American enrollment) shows the percentage of African-American student enrollment in each CMS high school in 2009 as well as the number of AP subjects offered at each school. The other tabs show enrollment of Hispanic and white students with the same AP subject availability.

Notes: 2009 data are the most recent available by the Office for Civil Rights. 2012 data will be released in fall 2013. The number of courses reflects the types of AP classes offered. These data are reported in categories such as foreign language, science or mathematics, and not by specific subjects within categories. Scroll below to see the same information presented in a table, with separate entries for multi-program campuses such as Garinger and Olympic.

The schools with the highest African-American student enrollment typically have the lowest number of AP course offerings. The schools with 76 percent or higher African-American enrollment (with number of AP course offerings in parenthesis) are: Hawthorne (0), Turning Point (0) and Midwood (0) (Alternative Schools, no AP program available), West Charlotte (8), Phillip O. Berry Academy of Technology (9) and Harding (11). To compare, the schools with 25 percent or less African American enrollment are Providence, (18), Ardrey Kell (22), South Mecklenburg (22) and Butler (23). (Note: the overall enrollment in CMS is 45 percent African-American. Schools with African-American population substantially different from this base measure were used for comparison).

So what?

In addressing college-readiness in the district, CMS Superintendent Heath Morrison noted, “In order to determine the degree to which we are meeting this goal, we must identify college-readiness measures. These can be used to help us reverse-engineer pathways of success for all students with a focus on literacy, numeracy, and writing. We can begin by promoting increased participation in AP and IB [International Baccalaureate] courses and in SAT/ACT testing as well as providing support to strengthen student performance” [1]. These data show some of the challenges CMS faces as it strives to build these new pathways of success for all students, particularly low-income students of color.

In urban districts, equal access to AP courses will ensure options for a rigorous course of study for all students [7]. Moreover, beyond just an increase in course offerings and enrollment, equity in course quality must also be considered. If students are not offered equal educational opportunities, the likelihood of their success on AP exams and future college courses is significantly diminished [3]. CMS, like many urban districts across the country, should aim to remove all barriers to equal access and opportunity for all students, regardless of race and socioeconomic status.

[1] Morrison, Heath. (2012). The Way Forward: Listening, Learning and the Case for Change. Charlotte, NC: Charlotte Mecklenburg Schools.

[2] College Board (www.collegeboard.org) (2011)

[3] Hallett, R., & Venegas, K. (2011). Is increased access enough: Advanced placement courses, quality, and success in low-income urban schools. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 34(3), 468-487.

[4] Clark, D., Moore, G., & Slate, J. (2012). Advanced placement courses: gender and ethnic differences in enrollment and success. Journal of Education Research, 6(3), 265-277.

[5] Conger, D., Long, M., Iatarola, P. (2009). Explaining race, poverty, and gender disparities in advanced course-taking. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 28(4), 555-576.

[6] Corra, M., Carter, J., Carter, S. (2011). The interactive impact of race and gender on high school advanced course enrollment. Journal of Negro Education, 80(1), 33-46.

[7] Vaugn, E. S. (2010). Reform in an urban school district: The role of PSAT results in promoting advanced placement course-taking. Education and Urban Society, 42(4), 394-406.

[8] Taliaferro, J., & DeCuir-Gunby, J. (2008). African American educators’ perspectives on the advanced placement opportunity gap. Urban Review, 40(2), 164-185. doi:10.1007/s11256-007-0066-6

[9] Toldson, I. A. & Lewis, C.W. (2012).Challenge the status quo: Academic success among school-age African American males. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, Inc.

Ayana Allen is an assistant professor for Urban Education and Education Policy at Drexel University. She can be reached at ayana.allen@drexel.edu or 215-571-4582.

Abiola Farinde wrote this article while a graduate student working at the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute in 2011-2013.

Chance Lewis is the Carolyn Grotnes Belk Distinguished Professor of Urban Education. He can be reached by email at chance.lewis@charlotte.edu or by phone at (704) 687-5393.

Ayana Allen, Abiola Farinde, Chance Lewis