With mill preserved, new effort saves Loray’s village

Although Brian Miller grew up in Charlotte, he always felt drawn to Gastonia’s Loray Mill village, where his mother lived as a child.

The 30-block neighborhood with about 500 small houses surrounded the historic Loray Mill, site of a bloody 1929 labor strike that claimed the lives of Gastonia Police Chief Orville Aderholt and union activist Ella May Wiggins.

When Miller, a band director and adjunct professor of music at Louisburg College and Vance-Granville Community College, learned from a Gastonia friend that the nonprofit group Preservation North Carolina was restoring some of the Loray village houses and offering them for sale, he could hardly believe his good fortune. One of the houses was right around the corner from where his mother grew up. He’s the first person to purchase a property in Preservation North Carolina’s latest restoration project.

[highlight]Scroll below to see historic Lewis Hine photos of children working in Loray Mill[/highlight]

“I’m reconnecting with my family heritage,” said Miller, 44, of Louisburg. “I felt that connection when I first saw the house and knew this was the right thing.”

At its peak in the late 1920s, the five-story, 600,000-square foot plant known as the “Million Dollar Mill” employed 3,500 workers, many who lived in the village. Firestone Textile and Fibers bought the West Gastonia building in 1935 and stayed until 1993 when most of the operation moved to a new tire cord manufacturing plant in Kings Mountain. Preservation North Carolina got the building in 1998 as a donation from Firestone and tried to find a developer for what was considered one of North Carolina’s most important historic properties and a Gastonia landmark.

It was a long and difficult process, but the first phase of a $50 million residential/commercial restoration began in April 2013. In March 2015, the grand opening took place. Now all 190 loft apartments have been occupied in the 600,000-square-foot building, and developers plan to launch phase two – 106 additional apartments – soon. Inside is a 14,000-square-foot fitness club, and opening soon is Growlers USA, a microbrew pub with 100 craft beers. Developers expect to get a coffee house, music studio and are in discussions with several national restaurant chains.

“We’re pleased with the success Loray has shown,” said developer Billy Hughes, a partner in the Loray Mill project. He hopes the mill’s revitalization will extend into the surrounding area.

The public can tap into the history of the mill and village in a 1,100-square-foot space that houses “Digital Loray” – produced by the Digital Innovation Lab at UNC Chapel Hill. The project, supported by Preservation North Carolina through a gift by Rick and Susan Kessell, is a digital collection of material related to both the mill and the mill village.

[highlight]“These can be very sweet residences, and the neighborhood can be a real charmer.” — Myrick Howard, Preservation North Carolina[/highlight]

Meanwhile, Raleigh-based Preservation North Carolina has shifted its focus to the Loray village, where 25 percent of residents own their own homes and 75 percent of the properties are rentals, many of them not well maintained.

The nonprofit has had successes with restorations of mill houses in East Durham, Edenton and near Burlington.

Usually, Preservation North Carolina acquires properties and sells them as is. The Loray Mill Village project follows a different approach. While some houses will be sold as is, the nonprofit group is renovating the rest. It owns 12 houses, and the goal is to sell 20 in the next five years.

During renovations, the houses will be transformed into modern, energy-efficient residences selling for around $100,000.

Protective covenants attached to the deeds require the properties to be sold to homeowners and to meet preservation standards.

“We are trying to lift the market,” said Preservation North President Myrick Howard. “We want to re-establish home ownership in the neighborhood. These can be very sweet residences, and the neighborhood can be a real charmer.”

This Loray Mill village house on Vance Street in Gastonia was moved one lot down. Photo: Courtesy Preservation North Carolina

Two basic house types – A and B – date from 1901. A third, Type C, was added when the mill expanded around 1921-22. House sizes range from about 900 to 1,200 square feet.

As the original village grew, with the mill owning the houses, the mill owners considered incorporating the village as a municipality, but the village and mill became part of Gastonia.

Before World War II, the company started selling off the houses. As the owners, typically retired mill workers, moved away or died, the properties fell to heirs. By the late 1970s, the neighborhood went into decline.

Fifty-nine-year-old Bubbles Styers has lived in the Loray neighborhood all her life and is encouraged by the mill restoration and the possibility of the village finding new life.

Her grandparents, Jack and Irma Kennedy, moved there in 1932 and lived in a three-bedroom house was built in 1902. Both worked in the Loray Mill, and later the Firestone.

Styers remembers children playing in the mill swimming pool and running in the streets of the sprawling village. When the shifts changed at the mill, hundreds of workers spilled outside, sometimes creating congestion on the sidewalks.

Loray Village was a tightly knit world where families knew each other and looked out for neighbors.

Styers lives in her parents’ old house on Dalton Street, just two blocks from the mill.

“I love it here,” she said. “I wouldn’t want to live anywhere else.”

According to Styers, some in the neighborhood are laughing at the notion that modest mill houses, even when renovated, will sell for $100,000.

“They think it’s funny,” she said. “They can’t see it. But they don’t understand.”

She’s impressed by the quality of new construction and feels doubtful minds will be changed when people see the final product – high-energy homes with granite counters, modern appliances and other up-to-date features.

“I think folks will be happy then,” she said. “They’ll believe.”

Jack Kiser, former Gastonia planning director, hopes efforts by Preservation North Carolina will draw homeowners to what may be the largest mill village in the state. Photo: Joe DePriest

Jack Kiser, former planning director for the City of Gastonia, worked on the Loray Mill project for 20 years. He’s Preservation North Carolina’s project manager for the village revitalization.

House restorations are in the early stages, but he likes to imagine what they’ll look like when completed.

Original features that are still in good shape, such as heart pine floors, will stay. The condition of many houses is mixed, but Kiser said that overall they’re of solid build and the lumber is good. Examining the progress at a house at 906 West Second St., until recently occupied by renters, he recalled what the 1902 Type A residence looked like when he first saw it. The roof sagged and front and rear walls were bowed in. The house had asbestos siding that had to be removed, abated and properly disposed of.

“It was far worse than the average house,” Kiser said.

But now he can picture it as a snug, modern, one-bedroom residence with new appliances, handcrafted windows, new foundation wall, insulated walls, and outside deck.

He hopes Preservation North Carolina’s effort in the village will draw more homeowners into “what may be the largest mill village in the state.”

“I’m very excited about what we’re doing here. This is a historic undertaking,” said Kiser. “We plan to be here for the long haul.”

A house in habitable condition, for sale “as is” in the west Gastonia mill neighborhood surrounding the Loray Mill. Photo courtesy Preservation North Carolina.

Gastonia Mayor John Bridgeman thinks the restored mill and village “will be a great shot in the arm for that side of town.” West Gastonia was once a thriving section of the city, with numerous textile mills and adjacent neighborhoods. But with a slow decline in the industry and plant closings, the west side also went into a decline, blighted in some areas with high crime.

Other strategies to boost West Gastonia are in the works. One is a major ballpark similar to the Knights’ BB&T Stadium in uptown Charlotte, where the Gastonia Grizzlies and other teams would play. It will be the centerpiece of a major sports complex. A committee is looking into the possibility of the project, which involves the City of Gastonia, Gaston County and the Gastonia Regional Chamber. “As we all join together, I think you’ll see more and more commercial construction on the west side,” Bridgeman said.

For Brian Miller, Gastonia has always occupied a special place in his heart. His honors thesis in history at UNC Chapel Hill was on the 1929 Loray strike. And he eagerly listened to family stories about the fabled mill and village.

“I immersed myself in Gastonia history,” said Miller. “I couldn’t get Gastonia off my mind.”

He plans to restore his newly acquired mill house to what it would have looked like in the 1920s. Because he bought it “as is” and was not interested in modern fixtures, he paid only $20,000. He already has antique light fixtures, and a Louisburg resident gave him a 1925 L & H electric stove that had been in storage since 1948. He remembers his mother telling him about her earliest stove that stood on legs.

Miller said the interior of his house is largely intact from the early 1900s with original beadboard walls and ceiling.

From his back porch, he can see the towering Loray building which dominates the village. Looking around the village itself, he has a vision of its successful transformation, over time.

“I look forward to taking my part in the revitalization of this historic neighborhood in West Gastonia and to see it thrive,” said Miller. “I’m proud to be the pioneer.”

Joe DePriest grew up in Shelby and lives in the Gaston County town of Cramerton. He is retired from The Charlotte Observer after more than 24 years as a reporter there. Reach him at jdepriest@carolina.rr.com.

HISTORIC LORAY MILL PHOTOS

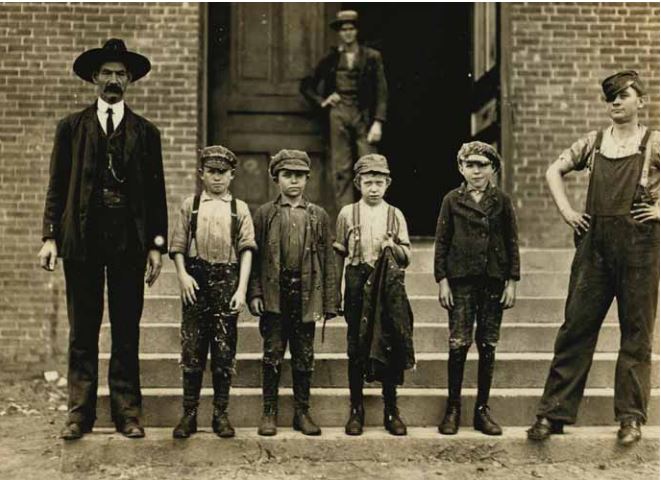

Photographer Lewis Hine worked as an investigative photographer for the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) between 1908 and 1924. His work took him to Gastonia in November 1908, where he photographed children at work at the Loray Mill, among other mills. Hundreds of his photos are available at the Library of Congress. Some of his Loray Mill photos are below.

Child laborers at Loray Mill in November 1908, photographed by Lewis Hine. Hine’s notes: “Boy with coat in hand is 11 years old. Been there 9 months. Started at 50 cents a day. Now gets 60 cents. Loray Mill. ‘When I sweeps double space I gets 90 cents a day, but it makes you work.’ (Look at the boy.) Two ‘infants’ appeared at the door, and vanished back immediately on seeing me.” Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, National Child Labor Committee Collection, [reproduction number, LC-DIG-nclc-01350]

In the Loray Mill village, November 1908, photographer Lewis Hine’s notes say: “Oldest girl, Minnie Carpenter, House 53 Loray Mill, Gastonia, N.C. Spinner. Makes fifty cents a day of 10 hours. Works four sides. Younger girl works irregularly.” Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, National Child Labor Committee Collection, [reproduction number, LC-DIG-nclc-01346]

Loray Mill, November 1908, photo by Lewis Hine. Hine’s notes say, “Girls running warping machines in Loray mill, Gastonia, N.C. Many boys and girls much younger. Boss carefully avoided them, and when I tried to get a photo which would include a mite of a boy working at a machine, he was quickly swept out of range. ‘He isn’t working here, just came in to help a little.’ ” Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, National Child Labor Committee Collection, [reproduction number, LC-DIG-nclc-01342]

Loray Mill, November 1908, photo by Lewis Hine. Hine’s notes say, “Going home from Loray Mill. Smallest boy on the right hand end, John Moore. 13 years old. Been in mill 6 years as sweeper, doffer and spinner.” Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, National Child Labor Committee Collection, [reproduction number, LC-DIG-nclc-01354]

Joe DePriest