NoDa perceived: past, present and future of a mill village

Not that long ago, a few aging blocks in a declining, working-class neighborhood revived from the dust and grit of the textile mill era as Charlotte’s home-grown arts district. By the mid-1990s, galleries and off-beat music venues replaced empty storefronts. Nightlife began to flourish, and the acronym “NoDa” took hold, affirming a new identity.

In some respects, the 2020 version of North Davidson Street hasn’t changed. It retains much of its historic ambience, including Fire Station No. 7 (1935), and Hand’s Pharmacy (1912), currently housing Cabo Fish Taco, both designated as landmarks by the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission. Their facades front on the narrow, worn-down sidewalks and render human scale to this compact tract of urban real estate. But the 90s heyday of local artists and performers, cheap beer and smoke-filled watering holes like Fat City is long gone.

A century ago, North Charlotte, as NoDa was known at the time, lay just outside the city limits. It had its own economy dominated by three textile mills, including one of Charlotte’s largest, the Mecklenburg Mill (1905). Rural white people who migrated to Charlotte in search of jobs took residence in workers’ villages clustered along a loose grid of feeder streets, all within easy walking distance to employment and a streetcar line connecting to downtown. (See photo below of renovated mill cottages on East 37th Street. Mecklenburg Mill and its water tower are in the background.)

Photo: Google Street View

Mecklenburg Mill shut down in 1969, signaling the demise of the textile era. Meanwhile, the neighborhood housing stock had expanded and diversified from its workforce beginnings to encompass a smorgasbord of architectural styles, sizes and unit types.

Today, scores of the original mill houses remain, some boasting expansive rear-yard additions, while many others have been demolished. Mecklenburg Mill has been converted to affordable housing, Highland Park Mill to market-rate apartments, and the third, Johnston Mill, will add another 230-235 housing units, including about 15 at below-market rates.

But adaptive reuse projects for the mills represent a mere fraction of the redevelopment resurgence of recent years. The opening of the Blue Line light rail extension in 2018 signaled a consequential shift in building size and scale, and the introduction of the “Texas-doughnut” apartment format to NoDa. These superblock buildings comprise of 3-7 floors of living units wrapped around a parking deck, and consume at least two acres of land. 30Six NoDa combines 344 living units along with 480 residential parking spaces and an additional 120 spaces for the public. It includes storefront commercial, the Wooden Robot microbrewery and a public plaza connecting to the 36th Street light rail platform (photo below).

Photo: Martin Zimmerman

Mercury NoDa (photo below), which frames the Neighborhood Theatre and adjoining storefronts, has 241 apartments, an internal parking deck and an overall footprint that approximates two city blocks. Both projects replicate the jumbo-scale template that permeates the South End, parts of Uptown, South Park, and Central Avenue towards Plaza Midwood, with density levels as high as 70 living units per net acre.

Mercury NoDa apartments. Photo credit: Google Maps

At lower densities, local developer Saussy Burbank is completing its second high-end townhouse project on the edge of the Highland Mill property and a third at 36th street and Spencer. Smaller builder-developers are buoying up the “missing middle” niche. These projects are double or triple the density of neighboring detached houses (photo below).

Photo: Martin Zimmerman

The outbreak of COVID-19 in March didn’t dampen developer investment. By then, several entities had already expanded into NoDa’s industrial zones. Flywheel Group’s Tony Kuhn is pursuing partners along the 88-acre Cross Charlotte Trail alignment for a proposed mixed-use district extending to the Sugar Creek light rail station. Brooklyn, N.Y. developer Avery Hall is under contract to purchase parcels bordering North Tryon, and local developer Clay Grubb is on track to purchase the 6.8 acre Herrin Ice property across 36th Street from the light rail station.

Light rail connectivity, a council-approved transit supportive zoning framework, a relentless pro-growth business culture, and a market willing to pay more for the NoDa ambience — for better or worse, these factors will continue to drive development for the foreseeable future.

Jacob Horr: President of the NoDa Neighborhood and Business Association

Besides family activities with his wife Caroline and two-year old son, Ben, Jacob Horr toils evening and weekend hours on behalf of neighborhood interests as the volunteer President of the NoDa Neighborhood and Business Association. Jacob is also their liaison with developer teams and city agencies when rezoning entitlement petitions are filed. Jacob resides a few blocks from Amélies French Bakery ‘s upcoming 36th Street relocation. His remarks below represent his own views, and are not necessarily those of the NBA members or its Board of Directors.

Besides family activities with his wife Caroline and two-year old son, Ben, Jacob Horr toils evening and weekend hours on behalf of neighborhood interests as the volunteer President of the NoDa Neighborhood and Business Association. Jacob is also their liaison with developer teams and city agencies when rezoning entitlement petitions are filed. Jacob resides a few blocks from Amélies French Bakery ‘s upcoming 36th Street relocation. His remarks below represent his own views, and are not necessarily those of the NBA members or its Board of Directors.

Contributing writer Martin Zimmerman interviews Jacob:

MZ: Let’s talk first about ethos. Webster’s dictionary defines “ethos” as “the characteristic spirit of a culture, era, or community as manifested in its beliefs and aspirations.” How would you define NoDa’s?

JH: NoDa is Charlotte’s epicenter for inspiration and the city’s historic arts and entertainment district. It is home to all walks of life that share a common dedication to promoting the arts and building community. The NoDa Neighborhood and Business Association (NBA) focuses on encouraging diversity and protecting our culture by:

- Being the voice for all our neighbors.

- Preserving and growing Charlotte’s “Arts District.”

- Promoting and expanding our stock of businesses, especially independent / small businesses.

- Preserving and protecting historically significant infrastructure, structures and existing single-family neighborhoods.

- Placing a priority on eco-friendly design / development.

- Maintaining and building affordable housing options.

- Maintaining and building a safe and pedestrian friendly neighborhood.

MZ:. The Neighborhood and Business Association is known to take a proactive approach throughout the rezoning process. Do you think the NBA has been effective, given that a pro-development culture has always dominated the Charlotte scene ?

JH: NBA recognizes that rezonings are inevitable in our neighborhood. As Charlotte continues to grow, our neighborhoods must grow with it. Over the past 20 years, city staff has agreed with NBA opinions on over 95% of the rezoning petitions. This is often due to: 1) the city and NBA understand smart growth and tend to come to the same conclusions; 2) we work hard to negotiate with developers to change their plans well before they come before City Council.

The success of any rezoning starts with vision, open communication, and good faith negotiation. We can’t stop the city from growing, but we can help shape it to maintain NoDa’s social, cultural and architectural values.

MZ: Charlotte’s a city that loves to do vision plans, and your neighborhood may be the only one that’s actually produced its own, volunteer-based document. But that was 10 years ago. Is it time for an update ?

JH: Every year, NBA sets our goals. One of this year’s goals was to refresh the NoDa Vision Plan. This process, which requires engaged community meetings, has been delayed due to COVID-19. When discussion resumes, we plan to focus on the density dynamic and the evolution of our culture as a community.

MZ: Is NoDa’s 2010 vision plan in alignment with City Council’s 2019 rezonings for transit oriented development (TOD)? Explain, if you can.

JH: TOD alignment rezoning marked the first major change in the Charlotte zoning code since 1985. It impacted dozens of NoDa parcels and involved tough discussions within the neighborhood, especially on density issues. Sometimes our vision plan was in alignment with TOD; in other instances, we felt specific land parcels were inappropriate. We worked with city staff planners to remove them. These included parcels with historic buildings and areas where we felt density would encroach on the form and scale of single family dwellings.

MZ: The Mecklenburg and Johnston mills are not the only examples of affordable housing initiatives endorsed in NoDa’s 2010 Vision Plan. Can you bring us up-to-date on what else is happening in affordable housing ?

JH: We work with developers to advocate for affordable units on all housing rezonings. Current examples include Tim McCollum at Revolve Residential for the 18-unit Atlas Homes project on Charles Avenue and Whiting (see photo below), and Harrison Tucker and his Cohab team at 36th Street and McDowell for up to 60 units. Atlas Homes includes two townhouse units for income-restricted residents; Cohab will also include three affordable housing units and ground floor commercial, with a below-market retail space for an independent small business.

The affordability equation often depends on density because land prices keep rising and open space is limited. Density is not right everywhere in NoDa, but it’s unavoidable if we want to achieve our affordability goals.

Atlas Homes. Photo credit: Martin Zimmerman

MZ: In the 1990s everyone loved North Davidson Street because it was so “un-Charlotte.” Some of my fellow urbanists would argue that today’s version gives off very different vibes; that it’s just a way station parlaying burgers and brews for young professionals. Is this an accurate characterization?

JH: At first glance, NoDa is not the same as it was in the 1990s. North Davidson is no longer lined with art galleries and we don’t have monthly gallery crawls with drum circles and fire performers.

That doesn’t mean we’ve lost our art. I believe art has expanded in NoDa. Most businesses have local artwork on display in their interior spaces, every weekend the streets are populated with local artists and craftspersons, and the neighborhood as a whole has become a gallery with murals on the sides of buildings, trashcans, and more. The makeup of people that move to and visit NoDa has shifted, but the people it attracts come here because they share a common thread of creativity, acceptance, and community.

MZ: If you stroll down Yadkin or 35th Street on a Saturday afternoon, you see joggers. You see parents, mostly white, pushing toddlers in strollers. You see new houses sporting two-car garages and a market value in the $600,000 – $900,000 range. All this raises complex questions about affordability, gentrification, and even suburbanization. Do these trends trouble you?

JH: I do worry about the impacts of rising costs and high-end, suburban-style homes on the make-up of the neighborhood. This is not a unique problem to NoDa or Charlotte, as these and similar trends can be seen in cities throughout the U.S.

When I walk around the neighborhood, I ask myself, “What am I going to do to protect diversity in NoDa?” It’s not easy to do. It’s not something an organization like the NBA can do on its own.

MZ: Modernist houses have arrived in NoDa. Some would argue their design doesn’t fit with NoDa’s layback eclecticism. There’s one on Faison Avenue where a mill house was demolished. Others are scattered throughout the neighborhood. Local government shies away from judging the aesthetic merit of architectural design. Does NBA?

JH: Aesthetically, much like everything else in NoDa, our architecture is eclectic. We encourage builders and neighbors to take risks and use imagination to bolster NoDa’s uniqueness. But we are not a local Historic District or an HOA with design review clout. And typically NBA doesn’t know in advance if a house will be built, because no zoning change is required.

We generally support designs in keeping with an urban mill village heritage. That includes front porches, large windows, heavy eaves, uniform setback along the street front, no front-loaded garages, on-street parking, natural materials, pedestrian-oriented lighting, and an urban streetscape.

MZ: Apparently, modernist design doesn’t conform to this criteria — as illustrated by the pink house below.

Photo credit: Martin Zimmerman

MZ: In 1990, NoDa’s mill houses were certified by the National Register of Historic Places. Since then, many have been torn down or seriously disfigured. Stewart Gray, Senior Preservation Planner with the Charlotte Landmarks Commission, argues that a local historic district modeled after Dilworth or Plaza Midwood can assure greater protections than the National Register. Why isn’t NoDa a local historic district?

JH: We looked at this a few times and each time we decided against. With the positive protections that come with a local historic district come other rules that would impact our ability to pursue art, whether that’s murals on the side of our businesses or on a homeowner’s garage.

Nevertheless, we fight hard to protect all of our history.

MZ: Should the Neighborhood and Business Association be involved in monitoring the industrial property redevelopment that Flywheel Group, Grubb Properties and other developers are pursuing? If so, how?

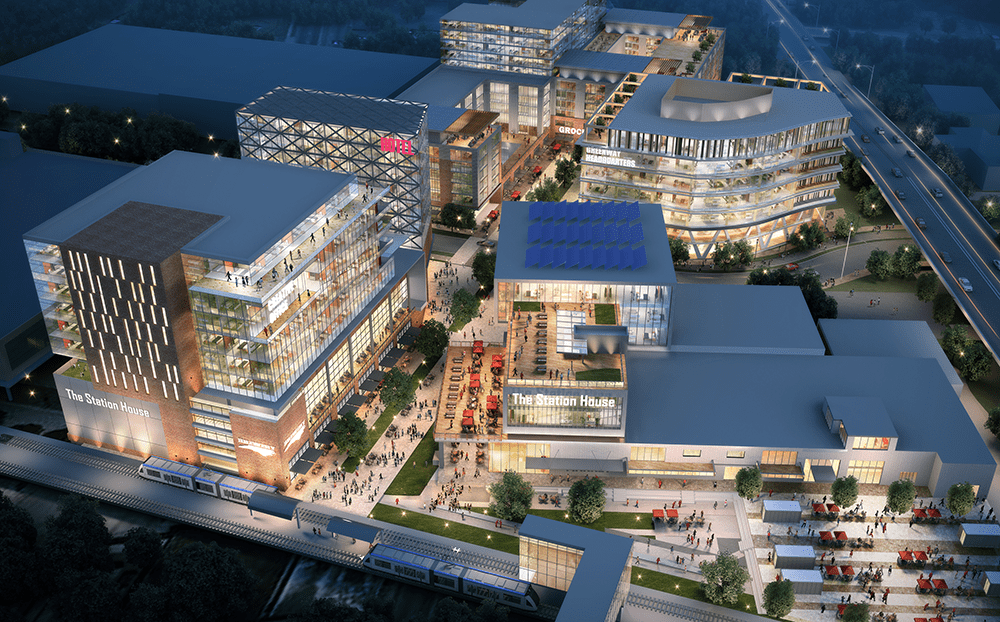

JH: Yes. While these parcels don’t have the historic resonance that North Davidson Street has, they could heavily impact the rest of the neighborhood. On the other hand, we are lucky to have local developers with strong visions. There is incredible potential to expand the area people think about when they hear “NoDa.”(See rendering below of Tony Kuhn’s mixed-use, high-density concept in the vicinity of the Sugar Creek light rail station. It combines new and adaptive-reuse structures, including a possible arthouse cinema for the Charlotte Film Society).

Image credit: Odell Associates/Flywheel Group.

MZ: Can you foresee a tipping point when “NoDa” transitions to a new name, not unlike the shift from “North Charlotte” that occurred in the 1990’s. What do you think might trigger such an identity change?

JH: I think “NoDa” is here to stay. NoDa’s as strong a community as it’s ever been and only has the opportunity to be better. We don’t intend to stop advocating and fighting for those things we are passionate about, and I can’t think of another Charlotte neighborhood that is more willing to do so.