Place matters and matters of place

I’ve been struggling with the question of what exactly makes a place feel like “a place.”

You may be baffled by that language, but if you think about it, you probably recognize that being in different kinds of places imparts a different feeling. Some locations feel artificial; others feel authentic. Age and beauty aren’t necessarily what matter. Artificial flowers can be plastic or silk, and real flowers can be wilted or fresh, but artificial remains artificial.

This mysterious characteristic of place can be defined, but it isn’t easy. It doesn’t fit in a checklist. It may not be in a rulebook. Perhaps it is in the making of a whole from the saying “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” In part it is whether the history of a place is visible, and the place feels connected to what’s around it. If you’re lucky, both visible and physical connections to surrounding areas exist.

After driving many miles and seeing various neighborhoods in the Charlotte region, I now have a better sense of the “quality that has no name,” as Christopher Alexander writes in his book A Pattern Language.

What would a checklist of the visible and physical attributes for a successful place look like? Any checklist would have to include:

- Connected streets that we feel comfortable walking beside and crossing.

- A variety of things to eat, see and do at various times of the day.

- Trees.

- Places to sit and watch others.

- The freedom to get around in many different ways: walking, biking, skating, public transport or driving.

In my quest to see the design qualities that evoke this sense of “place” – or lack thereof – I visited a handful of neighborhoods and developments in the Charlotte region. In each, I asked myself: Does this feel like an authentic place, or like a developer’s project?

NoDa

NoDa, a nickname for “North Davidson,” centers on East 36th Street and North Davidson Street in the old North Charlotte mill neighborhood.

Question: Place or development?

Answer: Place.

NoDa was the last place I visited on a day of touring that included Phillips Place and Birkdale Village. Walking down NoDa’s narrow, rather scruffy sidewalk, I looked into the lowering sun to see the rigidly defined silhouette of uptown in the haze. I knew then what Birkdale Village in Huntersville and Phillips Place near SouthPark mall were missing.

NoDa has a strong sense of place in part because it is surrounded by other places. It is oriented within a larger neighborhood, rooted with its own identity, grounded in the rest of the city. Many developments feel like disconnected “projects” because they are separated from the whole.

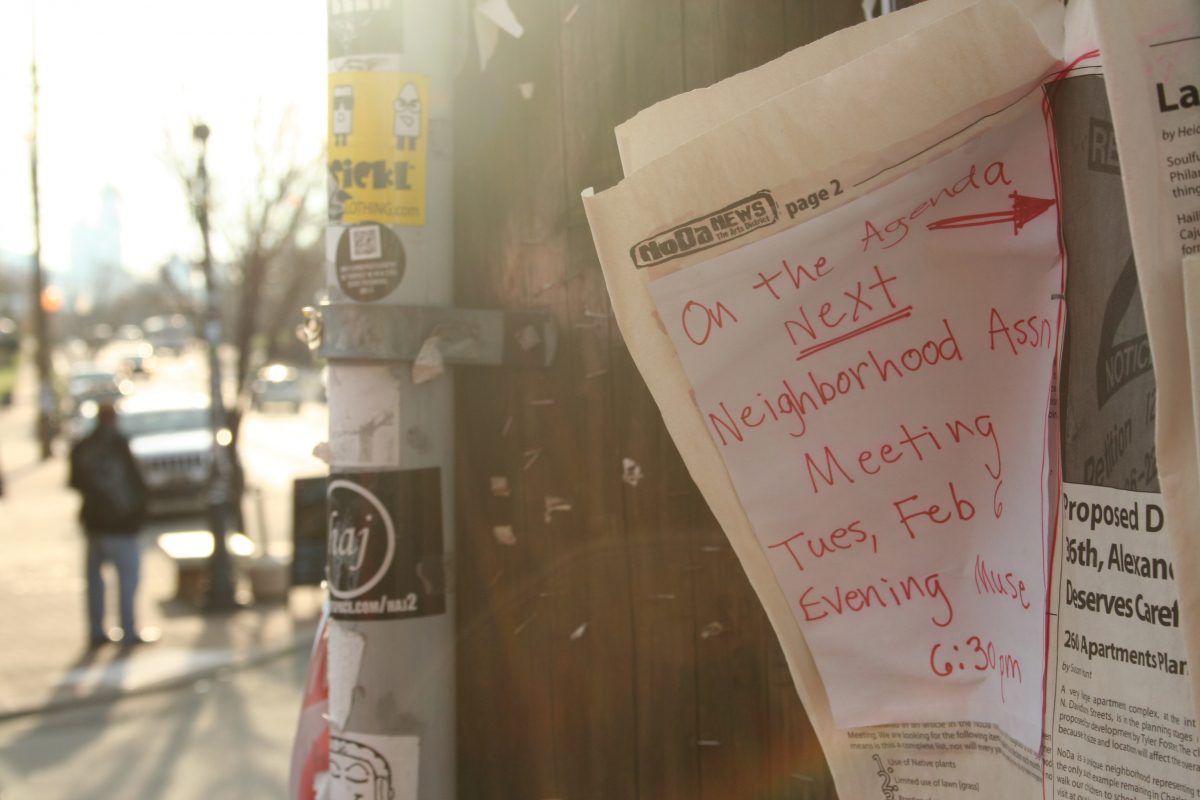

It’s interesting to see where objects like utility centers, light poles and trees are positioned on the street and how they’re used. A prime example: the awkward central positioning of light posts on the NoDa sidewalk. Set right in the center of the path, the poles create an obstacle for pedestrians. Yet at the same time, this encourages the use of the poles to post messages and advertising. Residents are making the most of what would be considered awkward design.

Take notice of the car-versus-pedestrian exchange when you’re in a place. In NoDa, it’s almost expected that someone will cross the street midblock, out into traffic. The narrow street width, traffic speed and activity patterns invite this. Pedestrians are bolder. Here, the car yields to the people, and it’s a nice feeling not to be scared to cross the street.

Tranquil Court: Infill or just fill?

Question: Place or development?

Answer: Place.

There is a difference when a development is brought to life from a green field or when it is infill, fitting into the existing context. An interesting example is Tranquil Court near Selwyn Avenue and Colony Road. The surrounding buildings vary in age and history. It fits within the pre-existing places – within the whole. The new development, from 2009, complements the neighboring buildings. The increased density from the new building brings more people, who help support nearby businesses. No gaping parking lots take up street frontage. The buildings, set right off the sidewalk, invite passers-by into a paint store, wine bar, frozen yogurt, grocery store, art galleries, restaurants and bike shop, among other businesses.

Harrisburg Town Center

Question: Place or development?

Answer: Development.

Harrisburg’s Town Center, set several blocks off busy N.C. 49, doesn’t even seem to believe in itself. There are exceptions to that generalization: Rocky River Coffee has a cozy and richly colored interior to contrast with the blankness of the waiting-for-development lots outside. Huge empty fields separate the Aldi’s grocery from the rest of the stores and restaurants near the Town Hall. There looks to be too much room for retail; many storefronts are empty. Look at the “places” that surround it: a busy N.C. 49, a gas station, Advanced Auto Parts, Food Lion, McDonald’s, residences on one side, fields, woods and parking lots.

Does it have potential to mature into a more authentic town center? If more buildings fill in the gaps, it’s a possibility. But will they?

And Food Lion is a place, right? People work there; others depend on it. But you arrive, shop and leave. You don’t linger. With no sidewalks, you’re not inclined to walk to anything nearby. It’s not designed for walking. There’s no clear way for pedestrians to get to the buildings without walking across seas of hot, boring parking lots. Even though the walk to the bank would be only a block and a half in uptown Charlotte, it feels like a great distance here. It’s designed for cars.

Enclosure – inside and outside

When urban designers talk about enclosure they don’t mean an actual ceiling but a subliminally comforting sense of something above your head, often shaped by trees and overhangs. This sense affects how we feel about a place. In Birkdale Village, the mix of evergreen and deciduous trees creates a full-bodied tree presence year round. Trees are great shapers of enclosed spaces. Their canopy makes us feel that the sky is not so high. Light posts can mark a line and form a subtle, permeable boundary along the sidewalk, also contributing to the sense of order. Notice where they are, and when you look ahead notice how a consistent line is formed, enclosing the sidewalk just a bit.

When urban designers talk about enclosure they don’t mean an actual ceiling but a subliminally comforting sense of something above your head, often shaped by trees and overhangs. This sense affects how we feel about a place. In Birkdale Village, the mix of evergreen and deciduous trees creates a full-bodied tree presence year round. Trees are great shapers of enclosed spaces. Their canopy makes us feel that the sky is not so high. Light posts can mark a line and form a subtle, permeable boundary along the sidewalk, also contributing to the sense of order. Notice where they are, and when you look ahead notice how a consistent line is formed, enclosing the sidewalk just a bit.

Pineville

Question: Place or development?

Answer: Both.

From an urban design perspective, the south Mecklenburg town of Pineville has done some things right in its one-block downtown. Fronted by some 20 storefronts of various colors, years and styles, it has places to sit, shady spots, lots of glass windows to tempt passers-by to venture inside and a mix of places to go. On-street parking provides a much-needed buffer from the steady traffic zooming through on a Saturday afternoon. You can cross the four-lane road only at one point, at the light. Only those who felt like scurrying between traffic gaps tried to cross on the northern end of the block at the railroad tracks. Although the one cafe, Two on Earth, was pleasant, cozy and its food tasty, other local eatery options would attract more people.

Unfortunately, this walkable street environment quickly ends. After this block, the building fronts are far off the street, and grass or surface parking lots are the first to greet the rare pedestrian. Just a half-mile east on N.C. 51, walkability falls off the radar. Four lanes of traffic on Main Street explode into 16 lanes. All one can see are the metal of cars, pavement and oversized advertisements for shopping centers.

The right combination

In the end, what makes a great place is a subtle combination of factors, some visible, some felt. Having its own identity, connecting to and fitting within and between other places is key. Compare that quality to an isolated development, surrounded by parking lots. Urban designers would say that if the only way to get there is to drive, there’s something wrong.

Pedestrians must dominate the character of the street; you can’t be afraid to cross a street. If an area can bring people to its streets to linger, wander, mingle, it’s on its way to being a great place – and an economically successful one as well.

Places also need to attain the patina that comes with age. A development built all at once doesn’t carry the same layers of history. Some well-designed developments may acquire those layers over time; others won’t.

Ultimately authentic places change over time as the forces of our culture and society fluctuate. But because location is static, and social patterns change, it comes down to the slower changing infrastructure that is present, shaping our feelings about the place – the streets, the shapes, sizes, and uses of the buildings, the sense of enclosure, and the sense of where we are in relation to our other favorite places in the city. When each area feels like an authentic place, it acts for the greater system of the city, benefiting the whole.

Views expressed in this commentary are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute, its staff, or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.