As projected construction costs surge, state road money dries up

New projections from North Carolina’s Department of Transportation show the state is $12 billion short on funding its next slate of transportation projects — nearly double the gap reported earlier this year. It’s a serious shortfall that’s expected to leave plans for roads, bridges and other infrastructure throughout the state waiting on the drawing board for years to come.

Earlier this year, the shortfall had been estimated at $7 billion. The NCDOT has been warning of funding shortfalls since 2020, when significantly less driving caused gas tax revenue to dry up.

The new problem, though, is sharply rising costs, which NCDOT massively underestimated. These costs are tied to rising prices for materials, labor, land acquisition and fuel, all of which make construction more expensive.

While projects already underway are likely to continue, some could be scaled back. The financial troubles probably mean some projects that were anticipated to start in just a few years could be pushed back to an undetermined date. In Charlotte, that includes dozens of projects big and small, from adding lanes to Independence Boulevard to widening N.C. 51 in Matthews and Statesville Road in Huntersville. The NCDOT is responsible for many of the biggest roads in Charlotte, including major thoroughfares like Independence Boulevard, Pineville-Matthews Road and W.T. Harris Boulevard.

Since last summer, the state has revised more than 1,000 separate estimates for right-of-way, utility and construction costs in more than 450 transportation projects, according to an NCDOT presentation. In some cases, costs have more than doubled from their initial projections.

“I doubt that there is much of the public, or even the elected officials, that understands exactly what’s going on,” said Andy Wells, an NCDOT board member from Hickory, in an interview this week with Transit Time. “This is a really big deal.”

The concerns are starting to rise statewide. In Hickory, officials worry about delays in widening I-40. In Wilmington, officials said in September that they’re concerned that a replacement for the aging Cape Fear Memorial Bridge could get delayed because of NCDOT’s future shortfall. In Charlotte, officials are starting to express concern about plans for Independence and W.T. Harris boulevards.

Effect on Charlotte

Tony Lathrop, a Charlotte attorney who serves on the NCDOT board and chairs its finance committee, said it’s too early to say what exact effects the funding problems will have on Charlotte transportation developments. But, he said, there will be impacts.

“It’s really pretty preliminary right now. There’s no way to say yet which projects here in our area are going to be affected, unfortunately,” he said. “It’s pretty clear there’s going to be some shuffling around.”

In some cases, officials are anticipating that local money will have to replace funding that would otherwise come from the state.

An NCDOT manager told Charlotte-area transportation planners at a meeting in September that the department is “value engineering” its existing projects in an attempt to reduce their costs. Value engineering is planner-speak for looking at ways to reduce costs by removing or altering nonessential features in a project.

‘Sticks and strings’ in University City: In Charlotte’s University City area, for example, that could mean eliminating nonessential improvements to N.C. 49 in front of UNC Charlotte. Tobe Holmes, interim executive director of University City Partners, said he heard recently from the Charlotte Department of Transportation that promised projects in the University area would be shaved down in order to cut costs in light of the funding shortfall.

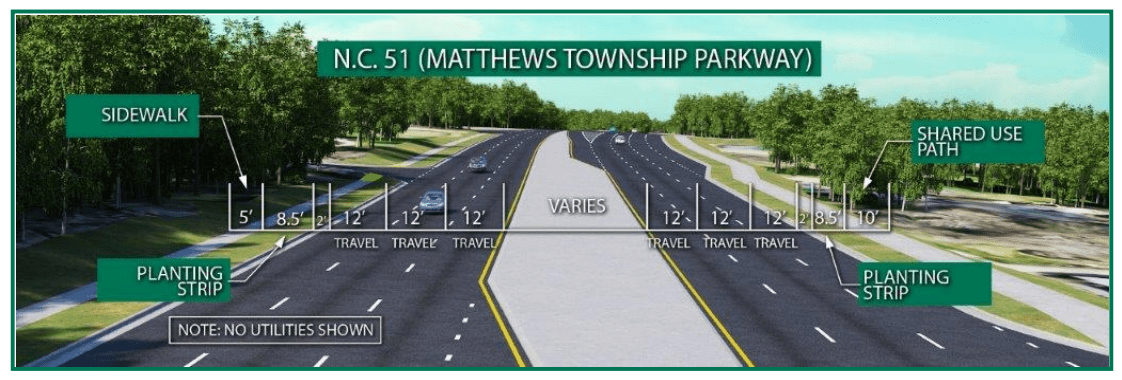

The state has been planning for years to convert more than a mile of N.C. 49 near UNC Charlotte into a six-lane “superstreet” with limited turns, designed to speed traffic. Holmes said some of the features the state considers “betterments” — such as wide sidewalks and design features that enhance walkability — would be in jeopardy if NCDOT finishes projects with only the “bare minimum” required.

“Instead of doing the 12-foot wide multi-use path, they’re going to put in the standard sidewalk,” he said. “Instead of doing the nice signal (utility) poles, they’ll put in those sticks and strings that aren’t great-looking.”

He said the planned cutbacks in Charlotte especially are “giving people heartburn, because a lot of the roads are in urbanizing areas.”

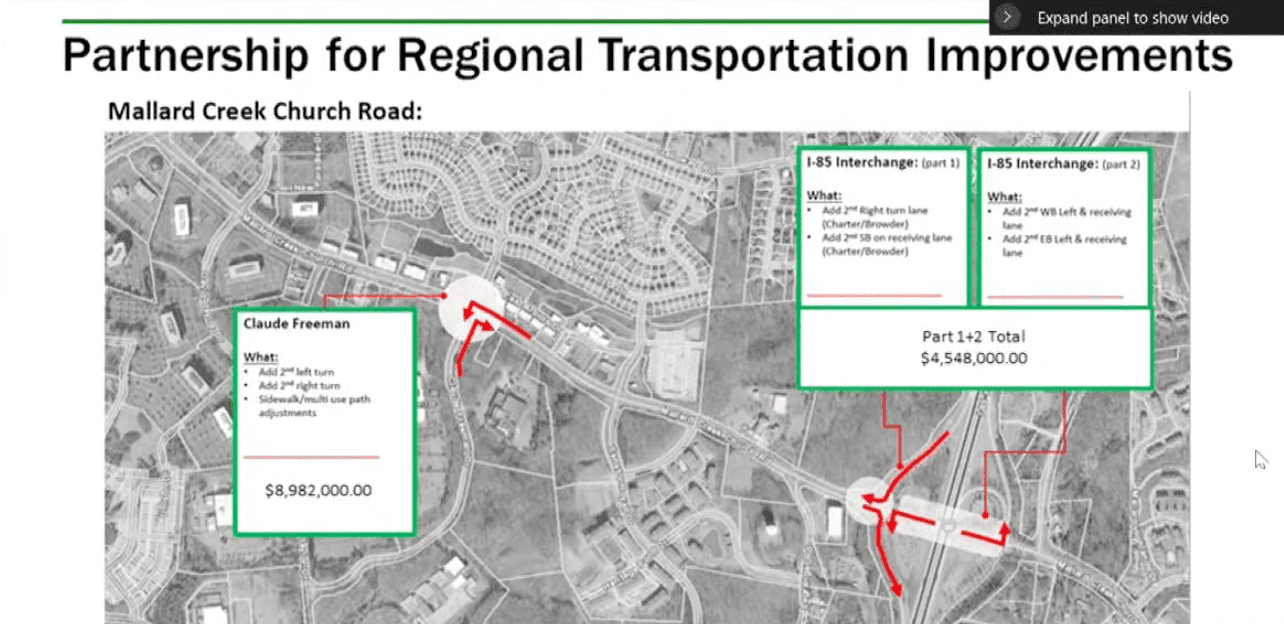

Shifting costs to the city? Monday’s City Council meeting could presage more of what’s to come as the state grapples with its funding shortfall. City staff recommended that Charlotte pick up about half the cost of improving two intersections on Mallard Creek Church Road in University City, at an expense to the city of about $6.6 million.

Those intersections, at I-85 and Claude Freeman Drive, are the state’s responsibility, but the city would like the projects accelerated because of next year’s anticipated opening of the large East Coast headquarters of insurance giant Centene Corp. Centene would pay the other half of the costs.

A slide from Monday night’s Charlotte City Council meeting shows two projects that would add turn lanes on Mallard Creek Church Road in University City. It’s a state road, but the city is proposing to split the $13.5 million cost with Centene Corp. to get the work done more quickly than the state will do it.

Some council members expressed concern that having Charlotte foot the bill for state projects would set a poor precedent.

“It sends a message — the message is Charlotte can afford to pay for itself,” said council member Ed Driggs. “Are we inviting an attitude on the part of NCDOT that our projects can be deferred because if it gets really critical, we’ll just pay for it ourselves?”

Behind the shortfall

The state’s latest projections show that, from 2024 to 2033, the NCDOT will be $11.6 billion short of having enough money to cover all of its committed projects. That’s a gap bigger than half of the total projected $21.7 billion available to spend over that decade.

The amount of the shortfall varies for each of the 22 budget “buckets” NCDOT divides its funding into. For Division 10, the geographic area that includes Charlotte and much of the surrounding region, the state’s projections show the NCDOT coming up $147 million short. But that doesn’t include the local impact of funding gaps on projects classified as having statewide or regional impact, for which the funding shortfall totals a whopping $9.5 billion.

In an interview with Transit Time, Joey Hopkins, NCDOT’s deputy chief engineer of planning, emphasizes that NCDOT is not low on cash. Rather, it is looking ahead and realizing that estimated costs for road projects are far higher than initially projected.

For the first time, projects that NCDOT has designated as having “committed” funding are likely to be revised as unfunded and delayed.

”This is a difficult process to go through,” he said. “I’ve been here 30 years, and I’ve never seen anything to this scale.”

One key reason the state’s funding shortfall projections increased so much is because the department switched from assuming 1% annual inflation to 3%. This year, economists have said prices are rising at their fastest levels in three decades.

Hopkins also said that part of the problem is the way NCDOT estimated costs.

“Some of it, too, was tied to us having outdated estimates, us using a tool to figure out estimates on these projects before you have design work done, before surveying is done, before you know how much right of way you’ll need,” he said. “We were using a cost estimating tool that highly undervalued estimates on some of these projects.”

He said the department has since changed the way it estimates project costs.

The NCDOT is headed by Transportation Secretary Eric Boyette, who has more than 25 years of state government experience including financial and technical leadership roles. He was appointed to the post in February 2020 by Gov. Roy Cooper.

Neil Burke, a program manager with the Charlotte Regional Transportation Planning Organization, said the state’s estimates seemed to be off dramatically in metro areas, where the cost of land needed for road expansions is soaring.

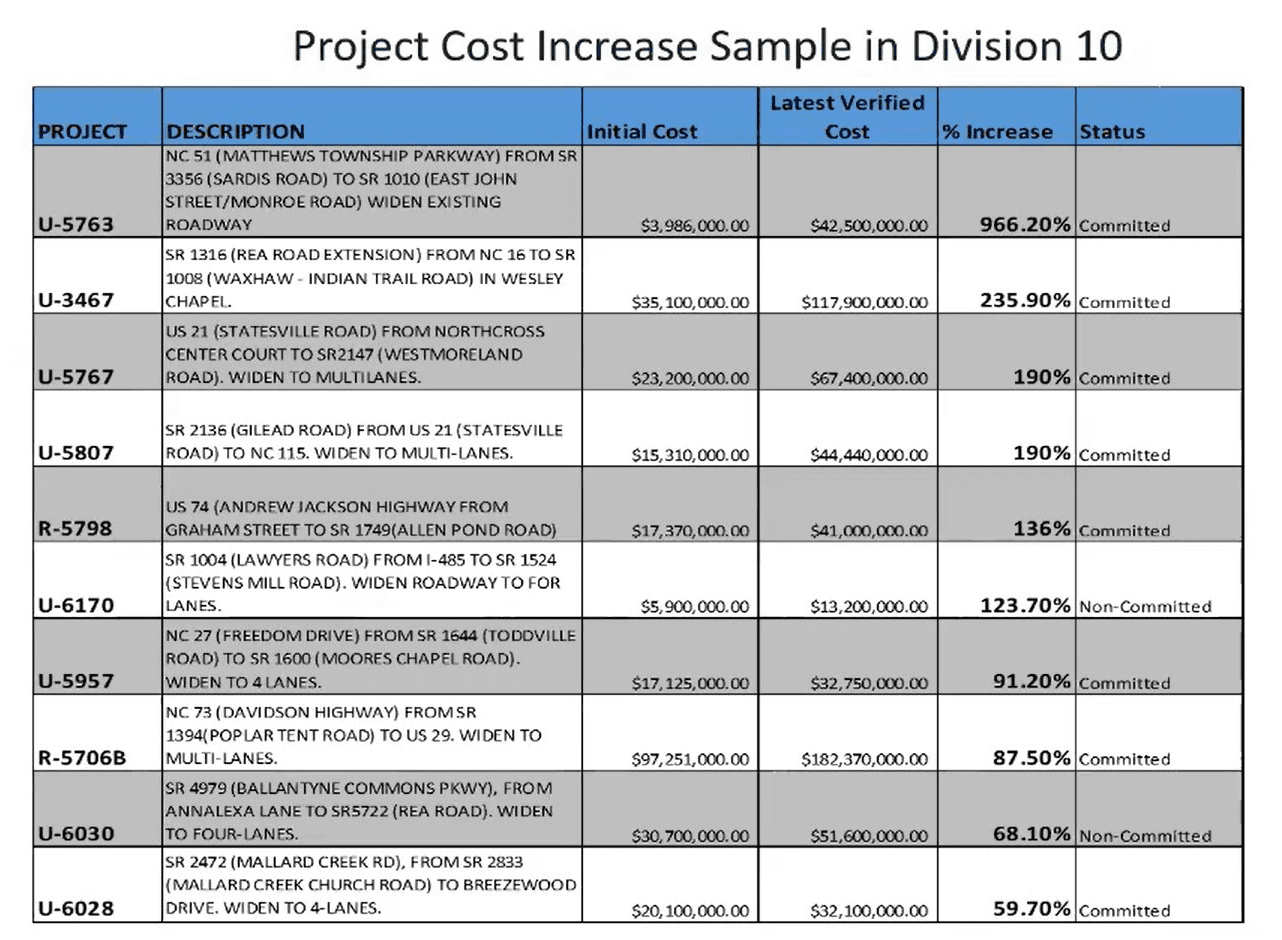

A document shared at a recent local transportation planning meeting showed huge changes in projected costs.

At a recent meeting of Charlotte-area transportation planners, an NCDOT representative shared examples of some of the surging cost estimates of local road projects, which rose between 59.7% (Mallard Creek Road) and 966.2% (Matthews Township Parkway).

At a recent meeting of Charlotte-area transportation planners, an NCDOT representative shared examples of some of the surging cost estimates of local road projects, which rose between 59.7% (Mallard Creek Road) and 966.2% (Matthews Township Parkway).

For instance:

- The widening of Matthews Township Parkway between Sardis Road and Monroe Road was initially estimated at $4 million. The latest estimate is $42.5 million, or a 966% increase.

- The widening of Freedom Drive from Toddville Road to Moores Chapel Road nearly doubled in cost, from $17.1 million to $32.8 million.

- The estimated cost of extending Rea Road from Providence Road to Indian Trail Road in Waxhaw more than tripled, from $35.1 million to almost $118 million.

The largest increase in cost on an NCDOT project in the Charlotte region is for widening N.C. 51 in Matthews to six lanes from four lanes. It was initially estimated at $4 million, but NCDOT now says it will be $42.5 million.

The largest increase in cost on an NCDOT project in the Charlotte region is for widening N.C. 51 in Matthews to six lanes from four lanes. It was initially estimated at $4 million, but NCDOT now says it will be $42.5 million.

One of the biggest projects likely to be delayed or scaled back because of surging cost estimates is the addition of express toll lanes on Independence Boulevard.

“That will definitely be a project that will have to be delivered over a longer period of time,” Burke said. The department is also “value engineering” the Independence project, and recommendations on what to pare back could come later this year or early next.

Hope from infrastructure bill?

Statewide, the NCDOT plans to release its new draft funding plan in December 2022.

Transportation planners say they are studying the recently passed federal infrastructure funding bill to determine how it might help. The initial read is that it might help some projects from being postponed but can’t overcome the magnitude of the shortfall.

This story originally appeared in Transit Time, a collaboration between the Charlotte Ledger, WFAE and UNC Charlotte’s Urban Institute.

Tony Mecia