Recession in Charlotte, Sun Belt: more people, more poverty

Population growth in Charlotte has always come with plenty of costs, but rising incomes and prosperity were part of the expected returns. Yet it turns out that during the recent recession and economic downturn, as population growth continued, economic growth sputtered.

Charlotte experienced a long period of population and income growth through much of the 1990s into the early 2000s. (Note the data on Charlotte in 2002 Brookings’ report “Growth Without Growth.”) In the period from 2000 to 2012, Charlotte’s metro population growth ranked fifth nationally. Raleigh, the other major metro area in the state, was ranked No. 1 in population growth during that period (based on metro areas that exceed 1 million residents – read more). Those two North Carolina metro regions were part of a widespread Southeastern population boom that included other hot spots like Atlanta and central Florida.

The Great Recession did not stop the population growth in this area, but it did put an end to the expectation that a growing population was always accompanied by economic advancement – something Charlotte and many other metros had come to expect. As the economic downturn lingered, people kept coming, while jobs and income slipped and poverty grew.

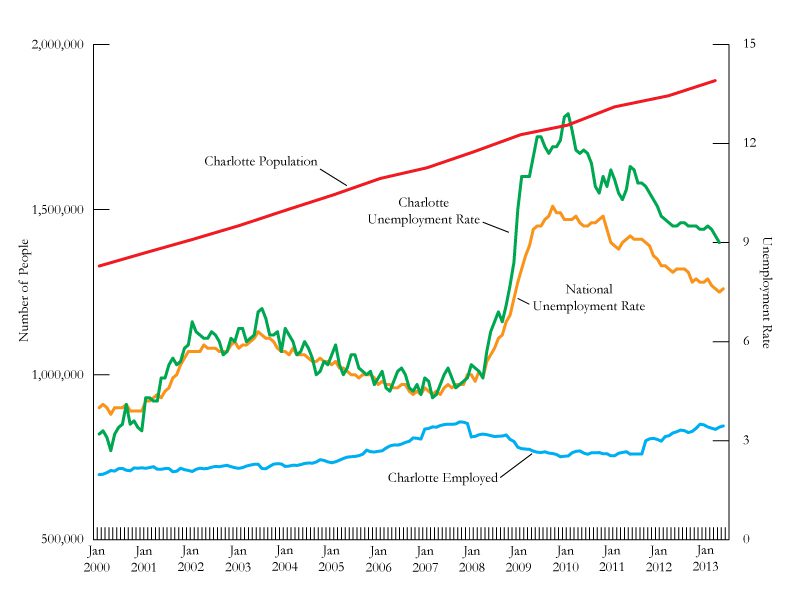

The graph below shows the steady, strong population increase the Charlotte metro experienced since 2000 compared to the region’s roller-coaster ride of unemployment and job creation.

Charlotte metro population and employment trends 2000 to 2013

Source: Bill Graves, UNC Charlotte.

This pattern of steady population growth in good times and bad has gotten the attention of urban researchers. Bill Graves, an associate professor of geography at UNC Charlotte who created the graphic above, has noted that many of the jobs associated with population growth are in lower-wage sectors. New employment numbers released Oct. 2 in North Carolina show that low-wage sectors are now producing 40 percent of jobs in Charlotte and half of new jobs in some metros in the state.

In the period since 2010, another pattern in population change has emerged. A large number of rural counties are losing population in the areas surrounding growing metros like Charlotte and Raleigh. This suggests that residents in struggling rural economies that have lost manufacturing jobs may be attracted to the lower-wage service sector jobs being created in urban areas.

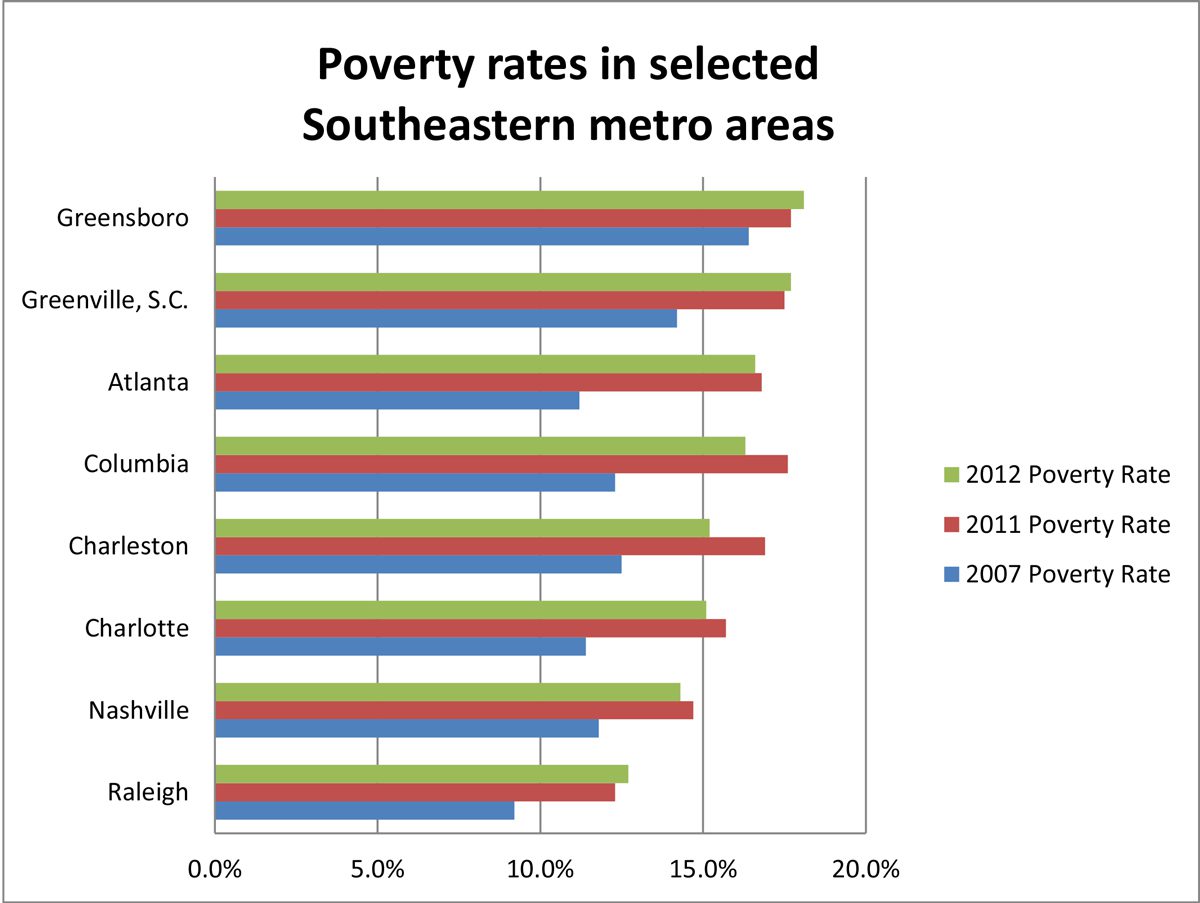

Increasing poverty rates reflect the economic stress on these southeastern metros with the onset of the recession (graph below). The recession caused poverty to spike in many areas of the country, but in these metros the increase in poverty rates accompanied continued increases in population, sometimes very strong increases, as was the case in Raleigh and Charlotte (for full report on metro poverty).

Source: Brookings, ACS Census data.

Richard Florida is one researcher who has looked at the question of population growth’s relationship to economic growth for metros around the nation. Florida asserts that “while many people use population as a way to gauge regional growth or decline, it actually tells us little about economic growth.”

Florida’s analysis of U.S. metros shows a clear pattern of strong population growth through the 2000s in the Southeastern U.S. But these same high-population-growth metro regions fall to the bottom of the pack in his measure of economic strength. Only energy-rich metros in Texas and Louisiana bucked the trend and showed strength in his measure of productivity growth (economic output per capita). The same pattern of high population growth without strong economic growth is evident in a large area of the Southwest including metros like Las Vegas (see maps and read more here).

Will this trend continue?

If rural economic growth does not improve, that may continue to add to population growth in metro areas in the Southeast. Strengthening economies in metro areas will also fuel continuing population growth.

The graph above shows that some Southeastern metro areas saw a slight decline in poverty rates from 2011 to 2012, a hopeful sign. However, the just-released employment report does not look as hopeful for the creation of higher-wage jobs in these metro areas.

As rural areas continue to struggle economically, pressure to move to where jobs are being created, even low-wage jobs, could prolong this pattern of urban population growth without commensurate income growth.

Harvard economist Edward Glaeser noted in his book Triumph of the City that poorer people come to cities, “because cities offer advantages they couldn’t find in their previous homes” (Glaeser, p. 70). As economic activity and people continue to gravitate to metro areas, especially in Southern states, the economic strength of the urban regions will likely be even more important to the states’ overall economic condition, and thus crucial to a growing proportion of overall population.