Segregation by Design

Charlotte’s neighborhoods (like those of many American cities) are highly segregated by race and economic status.

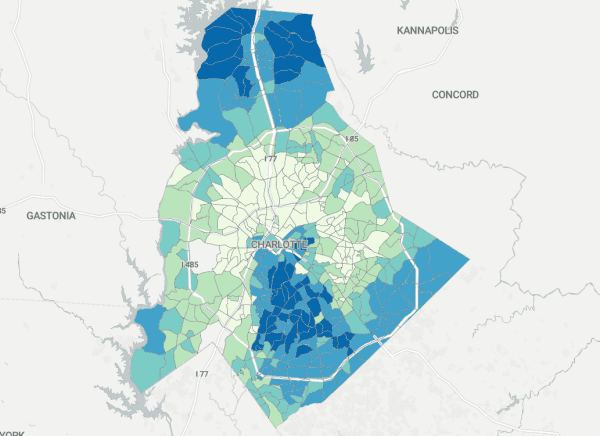

A quick review of the Charlotte/Mecklenburg Quality of Life Explorer’s interactive maps reveals that the data support this claim. The two racial categories with the highest share of the county’s population are White (44.7% of county residents) and Black (29.1%). But at smaller geographies—the Quality of Life Explorer presents data by Neighborhood Profile Area (NPA)— racial demographics are not proportional to these countywide figures (see Figure 1). The population of many NPAs are overwhelmingly White or Black.

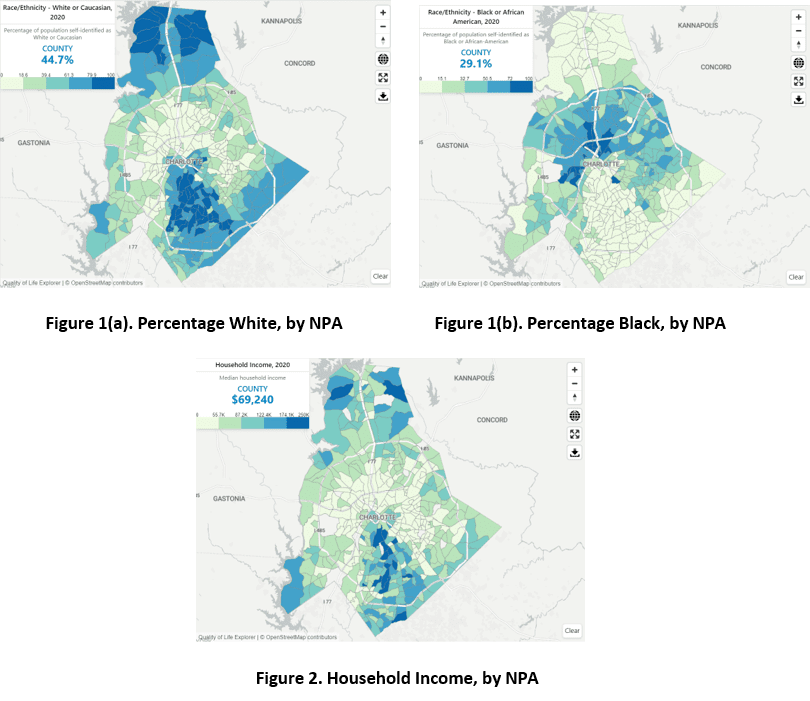

And the story is similar for household income (see Figure 2). Some NPAs have high concentrations of households with high incomes, while others have high concentrations of low-income households.

Very few neighborhoods in Charlotte-Mecklenburg reflect the underlying diversity of the overall city or county. Why is this?

Tom Hanchett’s classic book Sorting Out the New South (UNC Press) establishes that this hasn’t always been the case. In the aftermath of the Civil War, Charlotte’s residences were fairly thoroughly integrated racially and economically. Segregation wasn’t some sort of “state of nature”-like default. Segregation was the end result of a complicated process involving business and government (and—crucially—the interactions of business and government).

In southern states a major turning point came when the federal government’s abandonment of Reconstruction principles and protections allowed White supremacists (whose politicians ran on an explicit political platform of “White supremacy”) to re-write state constitutions and enact discriminatory laws that created the racist, undemocratic regime often described by the term “Jim Crow.” The timing varied somewhat across states. In North Carolina, this took place comparatively late, during and after the 1898 and 1900 elections. Patterns of racial residential segregation in Charlotte intensified in the aftermath.

[Read What made our city so divided? This book traces the roots]

But similar patterns emerged in cities across the U.S., driven by interactions between real estate developers and local governments. Two recent books—Paige Glotzer’s How the Suburbs Were Segregated and Jessica Trounstine’s Segregation by Design—explore this process. While neither book treats Charlotte as its subject, the stories they tell and patterns they describe generalize across American cities. We can use their findings to better understand how and why Charlotte became the segregated city it is today.

In How the Suburbs Were Segregated, Glotzer, a professor in the Department of History at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, presents a deep examination of suburban development in Baltimore. Starting in the late 1800s, real estate developers began acquiring property on the outskirts of the city with plans to build new residential neighborhoods.

The Roland Park Company built Roland Park, which would become one of the most elite (and exclusionary) suburbs in Baltimore. The developer had to generate interest in the project. Prospective buyers were at first reluctant to move so far from the economic activity at the center of Baltimore. So the developer’s marketers promoted the notion that distance from the city was a good thing—that Roland Park’s residents would enjoy health, beauty, and security because they were apart from the city.

More to the point, the developer argued, the benefits of suburban living were the reward for keeping one’s distance from the wrong kind of people. Black Americans, immigrants, Jews, Catholics, and laborers were presented as vectors for all kinds of undesirable contagions—crime, disease, and disorder. The developer thus deliberately sought ways to exclude such people (except as servants and laborers) and—crucially—to build a market of homebuyers who desired such exclusion. These means of exclusion included physical barriers (such as walls, hedges, and disconnected road networks), legal protections (restrictive covenants, once explicitly race-based zoning was deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in Buchanan v. Warley in 1917), and screening practices (the developer maintained lists of individuals to whom it would not sell property).

These practices were not limited to Baltimore, of course. National leaders were brought in to help design Roland Park—people like John Nolen and the Olmsted brothers. If those names sound familiar, that might be because of their work in Charlotte designing the neighborhoods of Myers Park and Dilworth, respectively. They were advocates of exclusionary practices like restrictive covenants, which can still be found in the deeds of many of Charlotte’s oldest “streetcar” suburbs (though such deed restrictions were rendered unenforceable by the Supreme Court in its 1948 decision in Shelley v. Kraemer). And even today Black residents make up a very low percentage of the population of early suburban neighborhoods like Chantilly (where less than one in fifty residents identify as Black), Dilworth (one in fifteen), Eastover (one in 250), Elizabeth (less than one in ten), Myers Park (less than one in thirty), and Plaza-Midwood (one in eighteen)—in a county where nearly one in three residents identifies as Black.

Glotzer describes how Baltimore’s developers were part of a larger, national effort to professionalize and standardize real estate development with the creation of the National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB) and the establishment of Realtors as credentialed professionals. Through regular communication and conferences, developers shared best practices for excluding individuals and families who were seen as detrimental to property values.

Furthermore, the development industry worked hand in glove with the federal government to establish federal policies from redlining to urban renewal. Many of these policies were built on the beliefs and preferences that the developers had worked so hard to create (in order to profit from): that a neighborhood’s property values were determined in large part by the type of people living there. These efforts were largely successful and underlie much of the built environment in American cities and suburbs, including Charlotte.

[Read How are Housing Choice Vouchers distributed across Southeastern Cities?]

Jessica Trounstine, a political scientist at the University of California, Merced, tells a similar story in Segregation by Design. The book starts with her examination of why segregation occurred. The two most common explanations are: one, that segregation is the product of private, individual choices and preferences; and two, that segregation is the result of racial differences in income and wealth. She rejects both accounts. Instead, she writes, “[s]egregation is not organic or inevitable. Rather, it is a matter of design pursued through the political process, offering spoils to those with political power.”

Trounstine finds that over the course of the twentieth century segregation was promoted by White homeowners and land-oriented businesses. They did this in order to maintain their property values and to control the provision of public goods. Segregation served these goals in two ways: by excluding residents who came from classes that were seen as undesirable and detrimental to property values; and by denying such people the distribution of local services and the decision-making regarding how the services would be provided.

These politically powerful White property owners pursued their objectives through the adoption of local land use policies like zoning. She finds that cities that were earlier to adopt zoning had higher levels of segregation later on. This segregation, in turn, led to inequalities in access to publicly provided goods.

Trounstine finds that in the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement, the geography of these dynamics changed. Processes of segregation that had historically occurred at the block or neighborhood level shifted to the city level. White property owners moved from the cities to suburban municipalities, whose jurisdictional boundaries allowed them to enact exclusionary policies to promote their economic interests and political power.

Trounstine argues that the resulting mix of policy and policymaking procedures produces racially disparate outcomes regardless of the individual beliefs of the White people benefiting from the arrangement. “Obviously, the level of racism among Whites is both variable and impactful for political and economic outcomes,” she writes. “But, in the end, because government policy generates segregation through land use, the consequences of this [individual-level] variation are reduced.” That is, the policies can be racist even if the individuals are not.

These two books provide a thorough account of the ways people with power exercised it via land use policy to promote their interests—including the acquisition of material wealth and more power. The authors credibly claim that these dynamics have literally shaped the communities Americans live in.

These books are not a comforting read. Their findings will likely elicit feelings in readers ranging from sadness to incredulity to anger. But they might help us understand why Charlotte looks the way it does. And they show us the ways our policies can have significant consequences for our lives and those of our children. We can choose different policies if we want different outcomes.