Six ways to turn SouthPark into a great urban neighborhood

Density alone does not equate to good urbanism. Density is a necessary ingredient, but raw density of jobs, housing or retail does not create a great street, much less a great place.

Parts of downtown Atlanta are a classic example of this. Those tall towers empty at 5 p.m., creating an employment ghetto in the evening, devoid of the vibrant street life around Midtown and hostile to pedestrian activity.

How hostile? When a friend and I attended a conference there—the topic was, ironically, “walkable urbanism”—he was struck by a car while crossing the street to the conference hotel. Thank goodness he rolled over the hood and was uninjured, but the incident is probably replicated too often to not be alarming.

The same is true of Charlotte’s SouthPark mall area. Originally a suburban mall on the edge of the city, it’s now one of the state’s largest shopping and employment centers. And recently, the level of housing within “walking distance” is staggering. (Notice the quotation marks around “walking distance.”) Hundreds of apartments are rising or being planned. Speculative office buildings are on the rise once again after a long hiatus since the 2008-09 recession, and it seems retailers, particularly those at the high end, are falling over themselves to find a place nearby.

Forty years ago, the area was a classic suburban mall district with few buildings higher than two stories. Today, few new structures are less than five stories, with a number of eight- to 12-story buildings rising above the mature willow oak canopy. Mixed-use buildings with housing or offices over ground-level retail are becoming more common. Yet with each new project, most of them higher in design quality than the previous, why does each rezoning discussion seem to devolve into a simplistic argument over the management of cars, whether parked or moving? And why does being a pedestrian along the main streets of Fairview Road and Sharon Road feel as hostile as in downtown Atlanta?

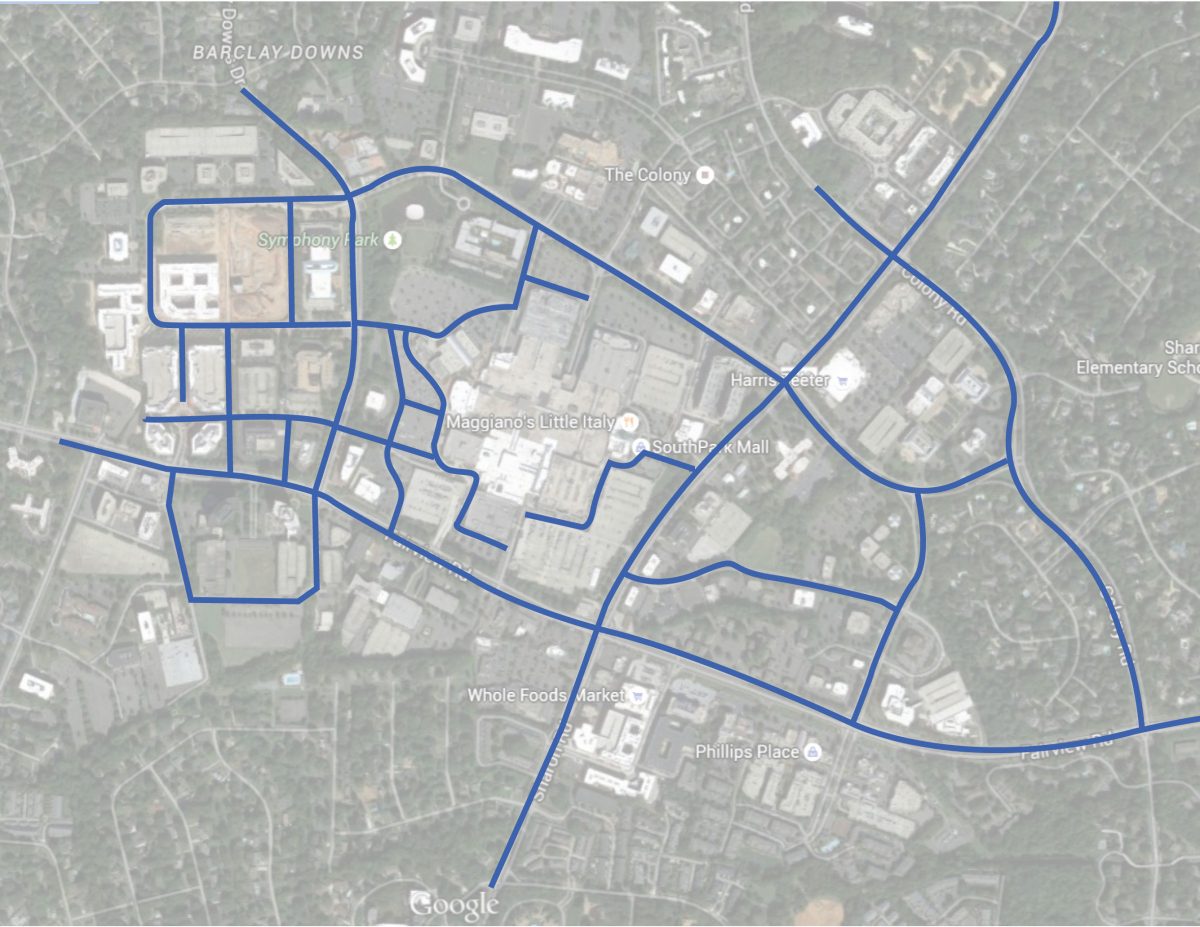

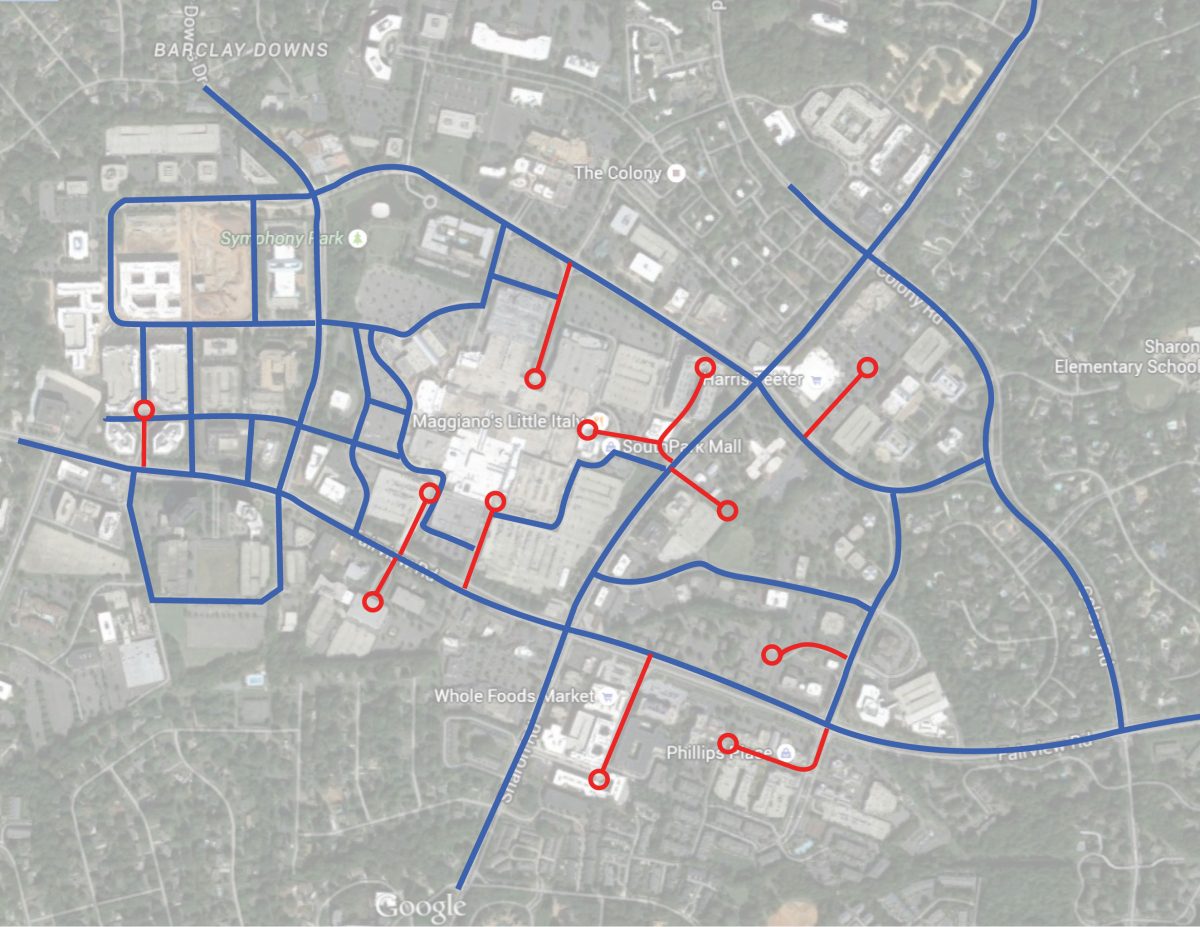

Perhaps it’s because there is a missing ingredient in the stone soup of great urbanism. Mixed-use buildings and density are not the only ingredients needed to cook up a vibrant, walkable environment that encourages people to shed their cars. As individual projects, they certainly deserve points for advancing the cause. But the recently completed Villages at SouthPark, Piedmont Row, and even the older Phillips Place feel more like cul-de-sacs than like main streets. They are visually—and often physically—disconnected from the larger street network. They create enclaves of dense development and fail to produce a great street for the community.

In short, each project is constructed in isolation from the others, and so each appears to fail at contributing to the larger public realm. Worst of all, the level of auto dependency is reinforced with the construction of each deck to provide free parking at capacities far exceeding what would be necessary if all were planned more comprehensively.

This is aggravated by the fact that most of the smaller infill projects fail to add value to the street edge. The blank walls of each CVS, Walgreens and office building conspire with their larger neighbors to destroy the potential for an interesting sidewalk trip that could inspire people to walk rather than drive.

The real culprit is the absence of a detailed urban design plan—and a zoning code to require the plan to be carried out. Those could knit each project together with a public realm that balances the needs of auto traffic with pedestrians, bicyclists and transit. Instead, individual projects are weighed on their individual merits and impacts, not on how they contribute to the greater whole. The Lorax asked, “Who will speak for the trees?” But, when creating great places we have to ask, “Who will speak for the humans?”

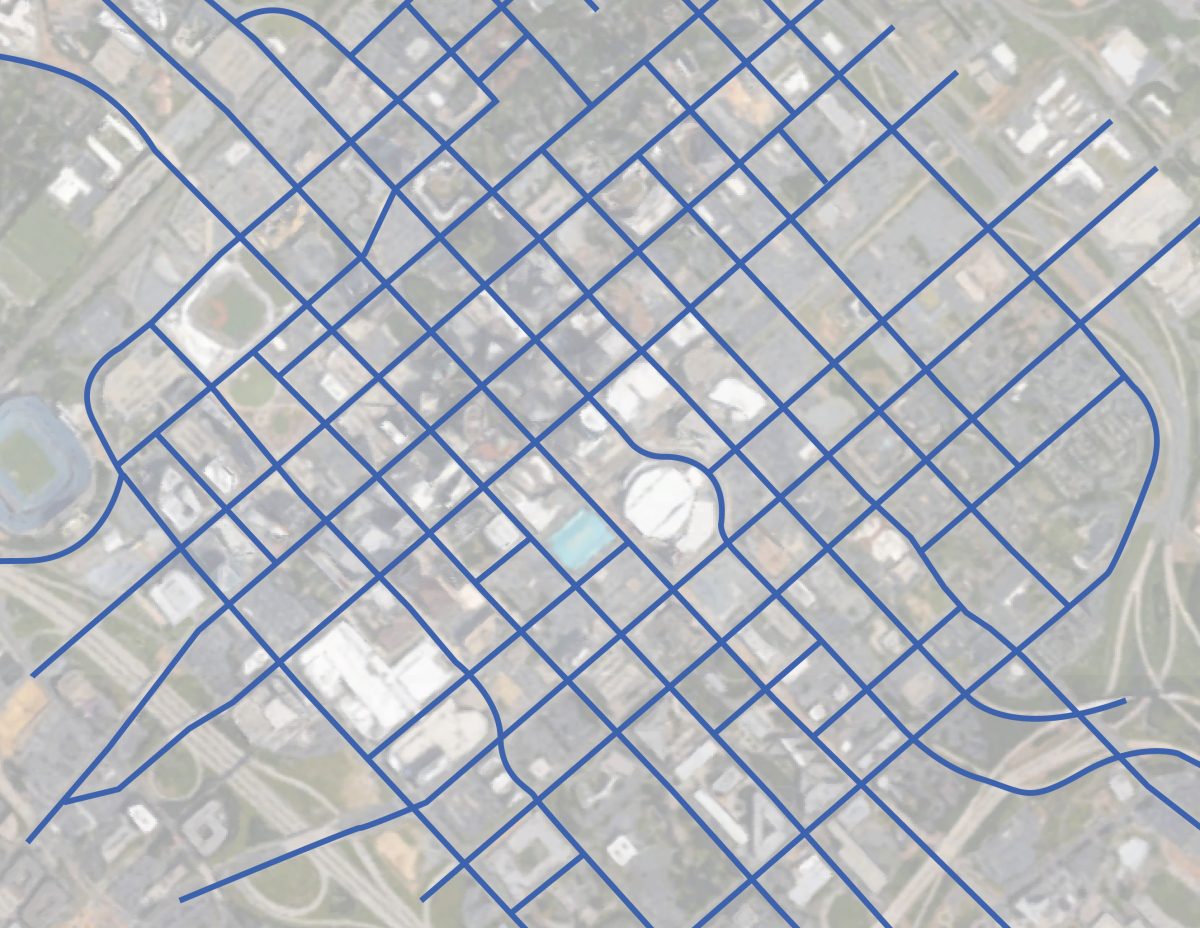

Many folks will throw up their hands and say the amount of traffic along Fairview and Sharon roads is too high to make a great street. That is because they are still thinking of the area as an auto-dependent suburban mall, and not as a downtown. Cities have a dense street network and complex set of different ways to get around, which provide choices for how you arrive and move throughout their area.

In the suburbs, everything is predicated on one mode of arrival— the car— and the shortest distance to the front door. In cities, the value lies in the aggregation of activities, parking is considered a shared utility, public space is given center stage, and each addition contributes to increasing value.

In the suburbs, everything is predicated on one mode of arrival— the car— and the shortest distance to the front door. In cities, the value lies in the aggregation of activities, parking is considered a shared utility, public space is given center stage, and each addition contributes to increasing value.

In the suburbs, the value rests solely in the final destination. Everything else is quantified as a nuisance—pavement, traffic, loss of trees, etc.

It’s not too late for these suburban teenagers to grow into urban adults. Large swaths of frontage along the major roads can still be claimed in the name of great urbanism. SouthPark mall can continue to urbanize and finally have a front door toward the community, not just into a parking lot. Here are six key things the SouthPark area needs to start doing immediately:

1. Update the SouthPark area plan. Last adopted in 2000, it has nuggets of great wisdom, but they’re buried among unnecessary data. Ground-floor design and mobility at the human scale are the most important elements. And most of all, stop thinking about the area as a suburban mall, and plan for it to be a city. (Read the SouthPark Small Area Plan, adopted in 2000.)

2. Implement a zoning code for the area that ensures a more predictable urban environment. Relying on a 15-year-old plan and a cumbersome rezoning process will never produce the best possible outcome, nor will rezoning it ad hoc.

3. Convert Fairview and Sharon roads to urban streets. Urban streets carry a lot of traffic but also balance the needs of cars, pedestrians, cyclists and transit. These streets are important to the overall city network, but for one mile can they be so much more?

4. Begin planning for more transit service. Begin building frequent, predictable service with rubber-tired trolleys circulating around the area. Plan for premium, fixed-guideway services in the future, such as dedicated rapid-transit bus lanes, streetcars or light rail.

5. Manage the district, not individual projects. Like Center City, South End and other mixed-use districts around the country, the collective assets and resources, both current and planned, should be collectively managed to make the most of their efficiency and to reduce the consequences of incrementalism.

6. Quit arguing about traffic. Congestion will never be solved. At this stage of city growth, urban design, walkability and planning for premium transit are much more critical to the conversation.

Michigan Avenue in downtown Chicago is considered one of the greatest streets in the country, and it carries about the same traffic volume as Fairview Road. What if blocks were created instead of parking fields? What if what you see along the street is designed generously enough to invite people to walk, as in its bigger cousin in uptown Charlotte, Tryon Street? What if transit was incorporated through the corridor, to make it truly accessible from corner to corner, and then connected to the greater region? In 50 years, would Fairview Road in Charlotte be counted among the greatest streets of the country?

Or, will it be measured only by the futile exercise of counting cars?

Craig Lewis is an urban designer and principal at Stantec’s Urban Places Group in Charlotte. Reach him at craig.lewis@stantec.com. This article is reprinted with permission from Lewis’ blog, City and Place.

Opinions in this article are those of the author and may not necessarily reflect those of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

Craig Lewis