Some ‘zombie’ subdivisions rising from dead

Grand stone gates give way to woodlands. Fire hydrants stand amid overgrown fields. Roads and sidewalks, some with weeds poking through the pavement, wind past expanses of empty lots. Wildflowers bloom inside brick foundations within sight of finished houses.

In the wake of the recession, many real estate developments appear frozen in various stages of construction across the Charlotte region.

| To see a photo gallery from Nancy Pierce of some of the subdivisions, click here. |

Most of these developments, sometimes called zombie subdivisions, ground to a halt when the economic downturn sucked the life from a once vibrant local real estate market. But several are reviving as developers regain their financial footing and, in some cases, propose new plans for the land.

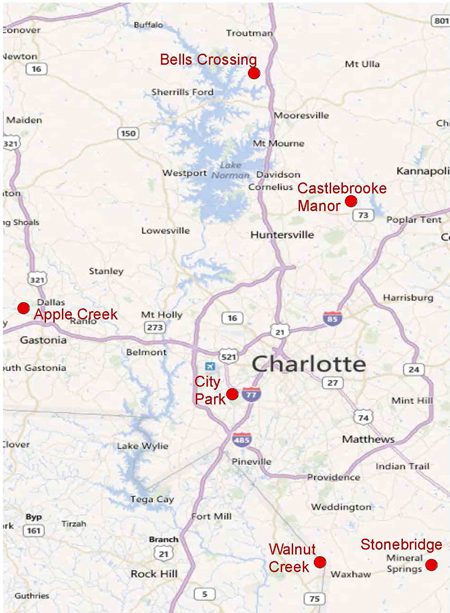

The map below shows the locations of the subdivisions examined here. They are only a sampling of developments that have been affected by the downturn.

At Castlebrooke Manor in Kannapolis, for example, the original developers built little besides castle-like entrance pillars and some streets on a 108-acre parcel before succumbing to foreclosure. Now a new developer plans to build about 230 homes – roughly three times as many as previously proposed.

At Castlebrooke Manor in Kannapolis, for example, the original developers built little besides castle-like entrance pillars and some streets on a 108-acre parcel before succumbing to foreclosure. Now a new developer plans to build about 230 homes – roughly three times as many as previously proposed.

The city’s Planning & Zoning Commission unanimously approved the request with conditions earlier this month, and Kannapolis planning director Kris Krider expects new home construction could begin early next year.

Some neighbors worry that turning Castlebrooke into “more of a cookie cutter-type subdivision” could hurt property values, increase traffic and add pressure to already packed schools, Krider said, but many people are thankful new blood has arrived to revitalize the project.

“By and large, everyone’s grateful someone’s actually picking up the pieces and starting over,” he said.

Similar momentum is returning to other once-stalled  projects elsewhere in the region:

projects elsewhere in the region:

• City Park: The economy slowed plans to build two hotels, as many as 2,500 residential units and 600,000 square feet of retail and office space at the 170-acre site of the former Charlotte Coliseum southwest of uptown, but developers are preparing to build a 284-unit multifamily project, according to Alberto Gonzalez, senior principal planner at the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Planning Department.

• Stonebridge: Developers envisioned more than 500 lots on almost 500 acres around an adjacent golf course in Union County, which has been  among the nation’s fastest-growing counties in recent years.The project stalled when the downturn hit and the county’s water and sewer capacity ran short, county planner Roger Horton said. Since then, the county’s water and sewer woes have eased, and new developers bought the property from a bank. The project remains far from complete – Horton estimated 170 lots have been approved for development and about half have been built on – but construction recently resumed.

among the nation’s fastest-growing counties in recent years.The project stalled when the downturn hit and the county’s water and sewer capacity ran short, county planner Roger Horton said. Since then, the county’s water and sewer woes have eased, and new developers bought the property from a bank. The project remains far from complete – Horton estimated 170 lots have been approved for development and about half have been built on – but construction recently resumed.

• Walnut Creek: This development, formerly  known as Edenmoor, was planned to include about 2,000 homes in Lancaster County, S.C. New owners renamed the project and launched a $6 million renovation late last year after large holes formed in roads and erosion clogged the development’s stormwater system during more than three years of inactivity, according to the Charlotte Business Journal. Ravines had eroded so severely that they threatened houses, CarolinaGatewayOnline.com reported in December.

known as Edenmoor, was planned to include about 2,000 homes in Lancaster County, S.C. New owners renamed the project and launched a $6 million renovation late last year after large holes formed in roads and erosion clogged the development’s stormwater system during more than three years of inactivity, according to the Charlotte Business Journal. Ravines had eroded so severely that they threatened houses, CarolinaGatewayOnline.com reported in December.

• Bells Crossing: Only a handful of 207 planned  homes – along with a swimming pool and clubhouse – have been built at this 226-acre, bank-owned property near Lake Norman in Iredell County, according to county planner William Allison. But the county has received enough recent inquiries about the project that Allison expects new developers likely will buy and resume it soon. “Usually, when we start getting this many calls coming in (about a stalled development) by appraisers and bank people, it’s an indication somebody’s seriously looking at the property,” Allison said.

homes – along with a swimming pool and clubhouse – have been built at this 226-acre, bank-owned property near Lake Norman in Iredell County, according to county planner William Allison. But the county has received enough recent inquiries about the project that Allison expects new developers likely will buy and resume it soon. “Usually, when we start getting this many calls coming in (about a stalled development) by appraisers and bank people, it’s an indication somebody’s seriously looking at the property,” Allison said.

Some stalled developments remain stuck, however.

Apple Creek, a planned residential development on about 100 acres in Gastonia and Gaston County, has seen virtually no vertical development in the seven years since the city annexed and rezoned most of the land, said Jason Thompson, Gastonia’s planning division manager. Thompson and prospective developers have discussed ideas for how to jumpstart the project, but no construction is imminent.

“I’m not aware of any progress of any kind,” he said.

The region’s stalled developments pose several challenges to local communities, planners say.

Most were supposed to be managed by homeowner associations, but that can be nearly impossible in a neighborhood where few – or no – houses are complete. It also can be difficult to trace responsible parties when developers go under or pass away. When banks own stalled developments, some don’t have the time or put forth the resources necessary to maintain them.

Often in such cases, residents will take it on themselves to mow grass or trim weeds near their development’s entrance to keep the place from becoming an eyesore, Iredell County’s Allison said.

In Gastonia, the city has worked with owners of stalled developments in an effort to combat vandalism and vagrancy.

“We’ve had to have people put in vehicle barriers” to keep racing or other illicit activity from empty streets, Thompson said. “There’s nothing on them – it’s just a road in the middle of nowhere.”

In Kannapolis, many of the stalled developments are being retooled to woo less-affluent buyers in the $150,000 to $250,000 range, Krider said.

In Castlebrooke’s case, the original developers’ more upscale target market has evaporated because many buyers can no longer afford big houses on large lots, said Anthony Sparrow, one of the project’s new developers.

Sparrow, president of Harvest Real Estate Advisors of Davidson, said he’s helped revitalize neighborhoods totaling about 700 homes in the past two years. He is confident Castlebrooke can succeed by offering smaller lots at lower prices. He also plans to add an amenity center with a pool, cabana and recreation facilities.

Fortunately for Sparrow, Castlebrooke has held up relatively well, even though people have dumped trash and trespassed with vehicles there, Krider said. The city has had to file liens on some properties when owners failed to properly maintain them, but that didn’t happen to Castlebrooke, he said.

Sparrow’s team should be able to use much of Castlebrooke’s existing streets, and although the developers would need to do additional sewer work to connect more houses, the main lines are sufficient to handle increased volume, Krider said.

In retrospect, it might not have been wise for Kannapolis to annex land so far from its core, because such moves can strain the city’s police force and necessitate new fire stations and water and sewer infrastructure, said Krider, hired late last year.

Now that Kannapolis has invested in such services, however, the city needs houses to materialize so it can generate revenue to cover its costs, he said. New construction could also bring jobs to the city and contribute to the creation of a new town center in the budding area where Concord, Huntersville, Davidson and Kannapolis merge, he said.

Despite those potential gains, Kannapolis must be careful not to “sell out” by accepting subpar proposals simply to get developments moving again, Krider said.

That’s why the city required Castlebrooke’s new developers to do things such as maintain a 50-foot buffer of undisturbed land around the property, add a new connection to a nearby road and adhere to architectural controls to minimize the appearance of “snout houses,” whose protruding garages take up most of the street frontage on narrow lots, Krider said.

Even though neighbors are sometimes nervous when a stalled development restarts, especially with a new configuration, communities can’t afford to let projects sit idle indefinitely, Sparrow said.

“Stalled projects ultimately cost everybody until they’re revived and get back to a stature where they’re livable and an asset to the community,” he said.