Is there a ‘right’ density? One expert says no

Julie Campoli’s new paperback, Made for Walking: Density and Neighborhood Form, is a must read for anyone in and around Charlotte who wants to know what it takes to make good neighborhoods into great ones. The book follows Campoli’s earlier Visualizing Density with photographer Alex S. MacLean; both were published by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, and both are photo-dominated. Made for Walking is a feast for the eyes. It overflows with 450 of Campoli’s street-level photos, handy diagrammatic maps, and an easy-to-digest text. Twelve of the most-walkable neighborhoods in the U.S. and Canada have been gleaned from four years of her travels and observations.

It is a book anyone can learn from, even experts. Her message is that density has its role, but only when understood along with other important elements of neighborhood form.

To make it easy to compare them, the neighborhoods she highlights are virtually identical in size – 125 acres. That size corresponds to a leisurely 20-minute walk from one end of the neighborhood to the other.

Although Campoli does not include any examples from Charlotte, similarities are evident. For example, South End, Dilworth, NoDa, First and Fourth wards and segments of East Boulevard, have some similarities with places like Denver, Colorado’s LoDo or Short North in Columbus, Ohio. Her 10 other model neighborhoods range from Little Portugal in Toronto, Canada, to the well-known Art Deco Flamingo Park district in Miami Beach, Fla.

And what are the elements Campoli pinpoints? Many are evident on the maps. Access to a diverse array of neighborhood-oriented services, predominance of street trees and public parks and high Walk Score ratings are all important. The reader may note that off-street surface parking lots are rare, block sizes are generally small and lot-by-lot construction is not subjected to the minimum setback requirements that zoning calls for in most Charlotte neighborhoods. Put in urban design terms, that means building facades act to frame streets and sidewalks as the public realm. Where longer blocks than normal exist, pedestrian ways are cut through midblock, to ease traffic flow (In Charlotte, try walking along the cut-through from North Church Street to Poplar Street in Charlotte’s Fourth Ward to see a local gem that works well).

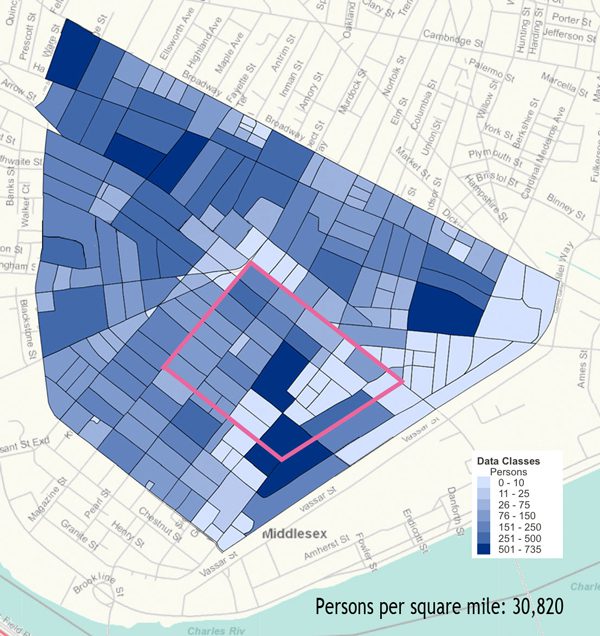

And what about densities? (Below: population density map of Cambridgeport neighborhood in Cambridge, Mass.)

Famed city critic and writer Jane Jacobs was of the opinion that “dwelling densities should go as high as they need to go to stimulate the maximum potential diversity of a district. … Densities can get too high if they reach a point at which, for any reason, they begin to repress diversity instead of to stimulate it.” Campoli’s concern is at the lower end of the density spectrum: the minimum population density that “makes public transportation viable and services available” (i.e. readily accessible without auto dependency).

In the neighborhoods Campoli examines, population density is defined by two metrics: First, by the number of persons per square mile, and second, by the number of housing units on a per block basis. For example, the urban redevelopment in the Cambridgeport district of Cambridge, Mass., equates to 30,820 persons per square mile. Albuquerque, N.M., illustrates the low end at 5,600 persons per square mile; if extended over an entire city, that equates to about 8 dwelling units per gross acre. To planners, that metric may seem quite low, but Campoli reminds us that this is still “more than twice the density of most American cities.” It should come as no surprise that, as a New South city built primarily for the auto, Charlotte’s overall density level hovers a bit under 2,500 persons per square mile.

Nevertheless, the Queen City itself is becoming more urban. It is running out of land to annex, household sizes are shrinking, consumers are beginning to save dollars and energy by choosing transit, walking or bicycling, and developers are seizing the opportunity to build in transit corridors instead of the auto-dependent areas. And yet, anyone who has watched a City Council rezoning hearing knows the debates about the “right” densities, especially housing densities, never seem to reach common accord.

That’s why it is so important to reframe the conversation in broader, and we can hope, less controversial terms.

Charlotte still has a long way to go. But to get there, it is essential to stay flexible. That means less contention over maximum tolerable densities, and paying more attention to the other attributes that contribute to better neighborhoods and a greater quality of life. Competing in a “green economy” will inevitably mean higher densities, and density can be a good thing. But the “compactness” that Campoli praises – which includes essential urban design elements – can create a win-win for better neighborhoods as well as a higher quality of life.