We know what doesn’t work. Why keep doing it?

Nationwide, schools of concentrated poverty have poor academic outcomes and limited educational opportunities.[1] Our local schools are no different.[2][3] Education reform is a priority across the political spectrum and throughout the community. But are we basing our reform efforts on accumulated evidence or simply on stories that tug on our emotions?

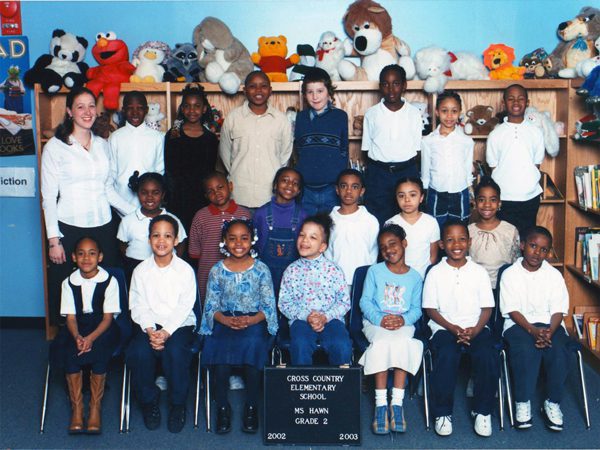

The students pictured above attended a hyper-segregated[4] school in one of the lowest performing districts in the nation, Baltimore. Yet the students in the picture were all high-performing, more than half of them identified as gifted. Despite what decades of school research describes – that segregated, nonwhite classrooms in low-income areas are typically low-performing – my experience as the teacher of this class was different.

We all have our own narratives about education. Pop culture, also, introduces powerful characters, from Lean on Me’s Joe Louis Clark (Morgan Freeman), walking the hallway with a baseball bat, to Michele Pfeiffer kicking up her cowboy boots in the 1995 film Dangerous Minds. The narrative: Any kid can learn if only the principal or teacher cares enough. Such education-reform narratives are powerful, but like most stories, they pick and choose among the facts.

In all this, money is a common theme. In Charlotte, the debate generally divides into: 1. Low-performing schools have too few resources, which causes the achievement gap. Or, 2. Low-performing schools have the resources they need, but it’s not well allocated, taking resources away from high-performing schools in more affluent neighborhoods farther from the center of the city.

Neither tells a full story based on evidence. Research makes clear that per-pupil spending (the amount of money spent to educate a child) is a complicated issue. It shows that per-pupil expenditure and achievement have a relationship, but not a direct correlation and that an increase in money alone does not mean an increase in achievement.

You don’t need to spend $19,000 on every student, the way Washington, D.C., does, to have good educational outcomes.[5] That’s the highest per-pupil expenditure in the nation, and it’s coupled with some of the lowest outcomes. In contrast, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools spends about $8,500 per pupil[6], with better results. Per-pupil expenditure is important, but there’s little evidence that reforms in school finance have closed the achievement gap or, in the aggregate, moved the needle on better student performance.

So is money the key lever to close the achievement gap? Probably not. But we do know that funding is important, and different schools have different per-pupil costs.

In Charlotte, the most expensive schools are segregated schools of poverty. Due to the challenges of segregated school environments, to teach those students requires additional staff and smaller class sizes, which costs more. In Charlotte-Mecklenburg, schools in more affluent areas spent less than $5,000 per pupil, while the highest poverty schools can cost upward of $13,000 per pupil.[7] Even with additional money, racially and socioeconomically segregated schools continue to show minimal growth, if any. This disparity is not necessarily due to poor facilities, teaching or leadership – although sometimes high-poverty schools can suffer from those things – but due to the challenges of putting so many extremely high-need students into the same building.

Can these challenges be met? Although films and narratives about individual classrooms or schools tell us they can be, evidence at the aggregate level tells a different story.

In Charlotte-Mecklenburg, 42 percent of schools are hyper-segregated, with 90 percent or more of the students of one race[8] – the most expensive kind of school to run, and the most difficult in which to increase student achievement.[9] Yet, in Charlotte-Mecklenburg and cities throughout the nation, increasing the number of racially diverse schools is rarely discussed as a viable school reform.

Instead, we keep trying to base reforms on anecdotal stories of individual triumph, instead of the facts that stare us in the face and challenge our pocketbooks.

Closing the racial achievement gap has been at the forefront of national educational reform efforts for decades, yet the only time the black/white achievement gap narrowed significantly was during the height of desegregation efforts in the 1970s and ’80s.[10] Cumulative evidence suggests that school diversity is an effective tool to improve educational outcomes and the federal government has declared this to be a “compelling interest” for our nation.[11]

My experience as a teacher showed me that a student can be poor, black, speak a different language at home and also do well in school. But my training and experience as a school administrator and researcher has shown me that the cumulative evidence points to diverse schools as better for kids and for communities.

Why is there such a disconnect between evidence and policy? It’s because complex problems are rarely solved with simple solutions. We humans like to think we make decisions based on data and logic, but we don’t. We have intuitive feelings and opinions; our normal habit is to develop a quick belief about a situation and then seek information to reinforce our belief. We want data to confirm what we already “know” is true. Researchers call this confirmation bias, and all of us are guilty.

Confirmation bias can look scientific, because it is based on data. But it’s humans who are analyzing the data, and we all have a large capacity for bias. I suggest this is why we make decisions and policy that run counter to what researchers describe, based on decades of data and research. We make decisions based on personal experience, narratives and anecdote. And when faced with evidence that counters our preconceived notions, we disregard it.

Educational research literature is surprisingly consistent: Diverse schools are better schools for a community.[12] Instead, across the nation, most school reforms are geared toward making high-poverty schools work. Evidence shows that high-poverty schools are expensive, incredibly challenging work environments and typically have poor academic and social outcomes. So while creating diverse schools is hard, the evidence shows that separate-but-unequal has proven to be impossible.[13]

Everyone in our community can play a role in trying to connect evidence to policy and minimize confirmation bias.

- Demand data-based decision-making. Decisions should be based on evidence and research, not anecdote or the extraordinary example.

- Want diverse schools in Charlotte? Demand a diverse school for your child, but don’t blame the school system. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools fought against the court case that ended the mandatory school desegregation plan the system was under, 1971-2001. Want to do even more for diverse schools? Then support housing initiatives to enable high- and lower-income families to live in mixed-income neighborhoods. Choose to live and work in diverse areas.

- Acknowledge that bias is a part of everyday life, but try to resist it; seek information to challenge your belief system. Constructively engage with people who have dramatically different ideas. Have coffee with someone who voted for the other guy. As you read, look critically: Are there sources? Are they credible?

In Charlotte, we don’t have to look far for a model of a community that worked together to achieve something many people said was impossible. Not too long ago, our local politicians and business leaders crossed party lines and sent their children to the schools that were making headlines.

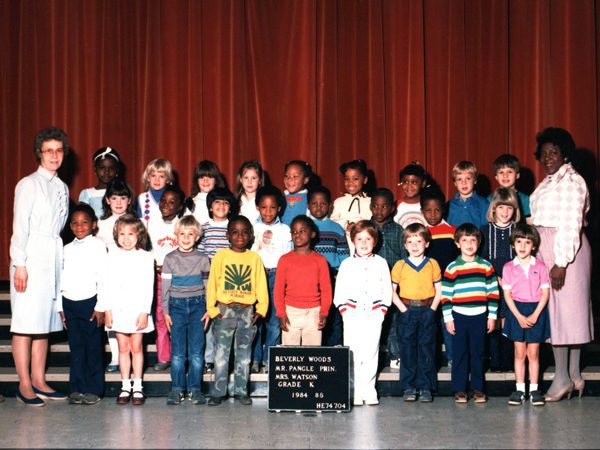

Although our school system was far from perfect, in 1984 CMS was held up as a national model of what a community could do when people came together and went past their biases in order to do what worked, for kids and the community as a whole.

That was the year I entered kindergarten. I was the beneficiary of diverse schools for 13 years. My hope is that one day soon, our community will move toward community building rather than community dividing, and will make wide-scale policy decisions based on what we know – rather than what we think to be true.

Views expressed in this commentary are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute, its staff or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

[1] Orfield, Kucsera, & Siegel-Hawley. (2012). The Civil Rights Project.

[2] http://maps.co.mecklenburg.nc.us/qoldashboard/#/k3/

[3] http://maps.co.mecklenburg.nc.us/qoldashboard/#/k10/

[4] Kozol, J. (2005). The Shame of the Nation.

[5] http://washingtonexaminer.com/d.c.-schools-outspend-nation-per-student/article/2500339

[6] http://www.cms.k12.nc.us/mediaroom/aboutus/Pages/FastFacts.aspx

[7] http://www.cms.k12.nc.us/cmsdepartments/accountability/spr/Pages/documents.aspx

[8] http://www.ncpublicschools.org/data/reports/

[9] See http://spivack.charlotte.edu/

[10] B.D. Rampey, G.S. Dion, and P.L. Donahue. (2008). NAEP 2008 Trends in Academic Progress (NCES 2009-479), National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Educational Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, Washington, D.C.). http://www.ets.org/Media/Research/pdf/PICBWGAP.pdf

[11] http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/guidance-ese-201111.pdf, http://spivack.charlotte.edu/

[12] Linn & Welner. (2007). Race-Conscious Policies for Assigning Students to Schools: Social Science Research and the Supreme Court Cases. National Academy of Education. http://spivack.charlotte.edu/

[13] Orfield, 2012, http://spivack.charlotte.edu/