What Charlotte can learn from other cities about taxing transit

Earlier this summer, the transit system that serves Columbus, Ohio, made a big announcement: It wouldn’t be seeking voter approval for a half-cent sales tax for transit.

“Now is not the right time,” Patrick Harris, the vice president of external relations for the Central Ohio Transit Authority told the Columbus Dispatch in July. “There are too many economic challenges in our region.”

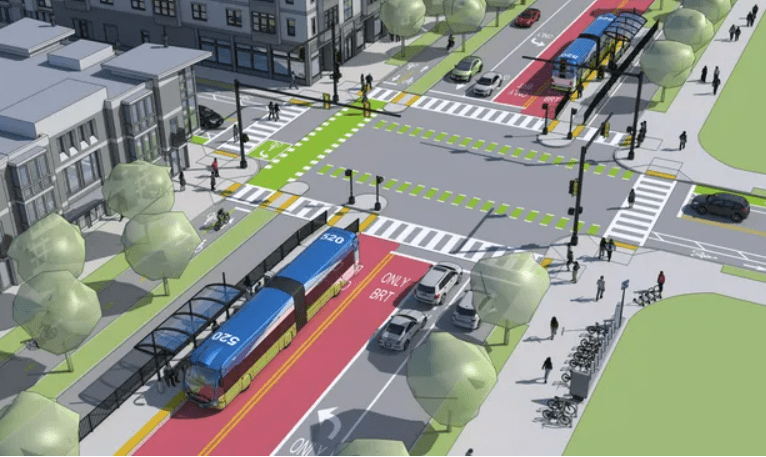

That half-cent tax would have built bus rapid transit lanes in Ohio’s capital city. Such lanes give buses their own dedicated right-of-way so they can avoid most traffic lights and not get stuck in congestion.

The transit system there isn’t giving up on the idea entirely; it’s just punting until 2023 or beyond.

Which leads to two questions: How have pandemic and post-pandemic votes on transit fared? And can Charlotte learn from the experiences of other cities?

At one time, Charlotte leaders hoped to have a vote on a penny sales tax this fall. But that issue has been pushed back until at least 2023.

Dana Fenton, Charlotte’s lobbyist in Raleigh, said this week the city still hasn’t made a formal proposal to state Republican legislative leaders about getting their approval to place a tax on the ballot. And a spokesperson for GOP Senate leader Phil Berger said the same thing: No ask from the city of Charlotte.

Charlotte’s plan would cost $13.5 billion. Most of that money would pay for the new Silver Line light rail, from Matthews to the airport. Money would also be set aside for the Red Line commuter train to Lake Norman; to expand the bus system; to finish the Gold Line streetcar; and for sidewalks, greenways and bike lanes. Some money would go to roads.

On “Charlotte Talks” on Wednesday, Mayor Vi Lyles said that the federal government will be spending billions of dollars on climate-friendly infrastructure and that Charlotte needs a local match to make sure it can access that money.

“I don’t want to leave money at home,” she said. “If we miss this, then Austin will take it, Dallas will take it.”

In Columbus, leaders were presumably talking about inflation as the “economic challenge” that caused them to not ask for a tax increase.

Columbus, Ohio has decided against holding a vote in November to build bus rapid transit. (Rendering from the City of Columbus)

It’s unclear if the economy will be a problem in Charlotte in 2023.

But the Charlotte Area Transit System has its own disaster, with a shortage of bus drivers and overall bus ridership down 75% since it peaked in 2014. And while other transit systems are starting to climb back, Charlotte’s bus system is going the other way, losing even more riders.

If you compare the last three months (April, May and June) to the same period in 2014, CATS bus ridership is down nearly 80 percent.

Other cities are moving forward with transit referendums this fall.

- Hillsborough County, Florida (home to Tampa) is still moving forward with a penny sales on the November ballot. The money would be split between roads and transit.

- And closer to home, New Hanover County voters will decide in November whether to increase the sales tax by a quarter-cent for more bus service in Wilmington.

In the November 2020 election, a handful of transit referendums were on the ballot.

Charlotte hopes to follow the lead of Austin, where voters approved Proposition A in November 2020. That measure raised the city’s property tax to fund a $7.1 billion transit plan.

City leaders visited Austin earlier this year to study what Austin is doing. Charlotte City Council hasn’t shown any interest in funding its transit plan with property taxes. But that plan would mean the city wouldn’t need permission from Republican legislative leaders in Raleigh.

There were other successful referendums in 2020 as well, in places like Seattle.

But there were also defeats in that same election. Voters rejected more money for transit in Portland, Ore., and Gwinnett County, outside Atlanta.

On “Charlotte Talks,” Lyles said the city “has a plan” to fix the bus system. She said the city needed to hire more bus drivers to make sure buses arrive on time. That can be done without a new sales tax.

And she said the city should enact the Envision My Ride program, which aims for more routes and more frequent service. That program requires a new funding source, most likely a new transit tax.

What will be the city’s measure of success before asking voters for more money?

Let’s say that the city hires enough bus drivers and can maintain a consistent schedule— but ridership is still down 65 or 70 or 75%.

Is that a success?

Steve Harrison is a reporter with WFAE, Charlotte’s NPR news source. Reach him at sharrison@wfae.com. This story was originally published as part of Transit Time, a newsletter produced jointly by WFAE, The Charlotte Ledger and the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute.

Steve Harrison, WFAE