Autonomous vehicles, flying taxis and…buses? Balancing present and future needs

How do you plan for the future and dream big while attending to the pressing needs of the day?

It’s a question that came up pointedly during Charlotte City Council’s annual planning retreat this week. With 385,000 people projected to move to Charlotte over the next couple decades, the city is grappling with increasing congestion and questions about how we’ll move around the community without spending hours a day in traffic.

To cope, council members are considering whether to put a 1-cent sales tax increase on the ballot this November. Mecklenburg County voters would get the final say on the tax, which would provide enough revenue over the next 30 years to fund the city’s portion of an $8 billion to $12 billion transit and transportation network. Such a referendum would face hurdles, however: The state legislature and county commissioners must agree to put it on the ballot, and the mayors of Davidson, Huntersville and Cornelius have already expressed their reservations because transit has lagged in the northern part of the county.

The priciest item on the city’s transit wishlist would undoubtedly be the 26-mile, east-west Silver Line light rail. But at the retreat, some council members asked another question altogether: Should we be focusing on autonomous vehicles, air taxis and other futuristic solutions instead?

“We can only go all in on one of these bets,” said council member Tariq Bokhari. He wants the city to focus on building the infrastructure (such as 5G service and electrical grid updates) to support self-driving cars, autonomous cargo vehicles and other technologies that are tantalizingly close but still over the horizon.

“Private companies are flying into outer space,” Bokhari said, emphasizing the pace of technological change. “There will be winning cities and losing cities in this battle.”

Council member Ed Driggs also expressed worries that light rail is too fixed and inflexible to adapt to the changes that disruptive technology might bring. The city’s “transformational mobility network” would also include greenways, bicycle lanes, road improvements and more, but light rail would be the costliest single item.

“From that time forward, we are committed to certain routes and certain technologies,” Driggs said of light rail.

James Barbaresso, a consultant with infrastructure firm HNTB, told city council members that a truly transformative level of autonomous vehicle adoption is still probably 30 to 35 years away.

“Can you wait that long?” he asked. “You still have needs the community has right now that have to be addressed.”

[Read more: Charlotte’s transit plan centers on economic mobility]

In Charlotte, roughly ¾ of commuters drive alone to and from work. And roughly half of the county’s workforce commutes in from other, surrounding jurisdictions.

It’s still not clear what long-term effect the covid-19 pandemic will have on our daily commutes. About 6 in 10 workers in the U.S. have switched to full or partial remote work, according to recent surveys, drastically cutting the amount we’re driving and erasing many traditional traffic peaks. Transit usage has plunged nationally and in Charlotte as a result. The Charlotte Area Transit System reported in November that ridership was down 61% compared to the previous year.

Barbaresso suggested council members view new rail lines and other high-capacity transit infrastructure as the “connective tissue” for the city’s transportation system — however that system looks in a few decades. Autonomous cars still take up the same amount of space as human-driven cars, after all, so traffic won’t disappear just because people aren’t at the wheel.

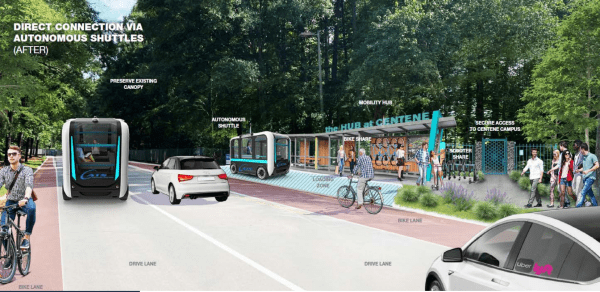

Assistant City Manager Tracy Dodson offered a glimpse of what that could look like in the future. Centene, a health insurance company, announced last year that it will build a 3,200-job East Coast headquarters in University Research Park. That’s more than 2 miles from the nearest light rail station, at J.W. Clay Boulevard, and across Interstate 85.

The company plans to partner with the city to create “autonomous circulators,” self-driving buses that would run between the campus and the light rail station to enable employees to use the Blue Line to get to and from work.

“They want to set the culture, when this campus opens,” Dodson said, “that (employees) have options other than just driving.”

I’m paraphrasing Councilmember Renee Johnson’s comments here but she was basically like, these plans are great for the future but we have places that don’t even have access to a bus right now #CLTCC

— Joe Bruno (@JoeBrunoWSOC9) January 12, 2021

Dodson didn’t present a timeline or budge for the project. But such “first mile, last mile” services, tying employment centers to transit stations that are out of walking distance for most people, could be an important piece of how Charlotte connects jobs to transit. For example, SouthPark is a bit over 3 miles away from the light rail station. Autonomous circulators in their own lane could be a way to link them.

Charlotte Mayor Vi Lyles said new, fixed-rail systems will be “the guideway and spine” for an overall system that also incorporates more futuristic technology, like self-driving buses.

Council member Renee Johnson said she wants to address pressing needs the community has now in addition to planning for future decades. Before the pandemic, CATS was working to reduce the average one-way bus trip from 90 minutes by shifting away from a hub-and-spoke bus map that required riders to come all the way into uptown, change buses and leave. Wait times on many routes can still be 45 minutes.

Fixing the city’s bus system might not be as flashy as self-driving cars and air taxis, but buses still carry a majority of CATS riders, many of whom don’t have cars.

“We are gridlocked and we need solutions now,” said Johnson. “Our streets are overcrowded. We have to lead for tomorrow, but manage for today.”