Is Charlotte car culture finally changing?

As a post-World War II, Sunbelt city that grew up in the age of the automobile, a car has long been pretty much a prerequisite for a comfortable and convenient life in Charlotte.

Despite the completion of the Blue Line light rail, added miles of greenways and bike lanes, and new options like fleets of shared electric scooters, Charlotte is still a city where more than eight out of 10 people drive to work alone. For most of us, a trip to the grocery store, picking up kids from swim practice and going to a doctor’s appointment require a car.

But Charlotte’s car culture is starting to show some more cracks, spurred by both long-term trends and the coronavirus pandemic, which has turned work life upside down for almost everyone. Ideas that have long bubbled around the edges of policy — like eliminating parking for some new apartments, building more pedestrian- and bike-only connections or closing popular streets to vehicle traffic — are gaining credence and becoming reality.

This doesn’t mean we’ll all be selling our cars anytime soon — at a sprawling, 310-plus miles, Charlotte is far from having the density, transit and other infrastructure citywide to support car-free or “car-lite” living for a broad swath of the public. The city still scores poorly on many rankings for walking- and biking-friendliness, such as the PlacesForBikes national city rankings released Wednesday, in which Charlotte scored 1.3 out of 5 for bicycle access, safety and rate of adding infrastructure.

And much of the pedestrian- and bike-friendly infrastructure that’s being developed is in uptown, South End and other denser, higher income neighborhoods — highlighting problems with unequal access in Charlotte.

Still, there have been enough changes in the past several years to consider whether they augur something deeper.

Car-free living

“We will evict you if you buy a car.”

That’s not a sentence you expect to hear coming out of a Charlotte developer’s mouth. But it’s what Clay Grubb, CEO of Grubb Properties, told Charlotte City Council about his newest planned development this week.

With 104 apartments in the west Charlotte neighborhood of Seversville, the building would be the city’s first with no parking — and cars explicitly banned. Grubb said he’s working with the Charlotte Area Transit System to add a bus stop to the apartment site, which is a bit over a mile from uptown and off a greenway.

City Council members were generally impressed with the project, which is up for a rezoning vote next month. Larken Egleston called it “fascinating.”

“I don’t think we could necessarily put thousands of units around the city like this overnight and expect them to be filled with people who live a carless lifestyle,” said Egleston. “But I do think we are a city now approaching 900,000 people…that certainly has a couple hundred folks who live a carless lifestyle.”

Because the building won’t include parking, Grubb said he won’t have to spend the $30,000 per space a garage would cost. That means rent will be $250 per month lower per apartment than it would otherwise be. Grubb also said he will make half the units affordable for people making 80% or less of the area median income ($44,250 for a single adult), without a public subsidy.

“This is a vote between cars and housing,” said Grubb, who views this project as a test case. “There won’t be a ton of these around the city until lenders can actually see it work.”

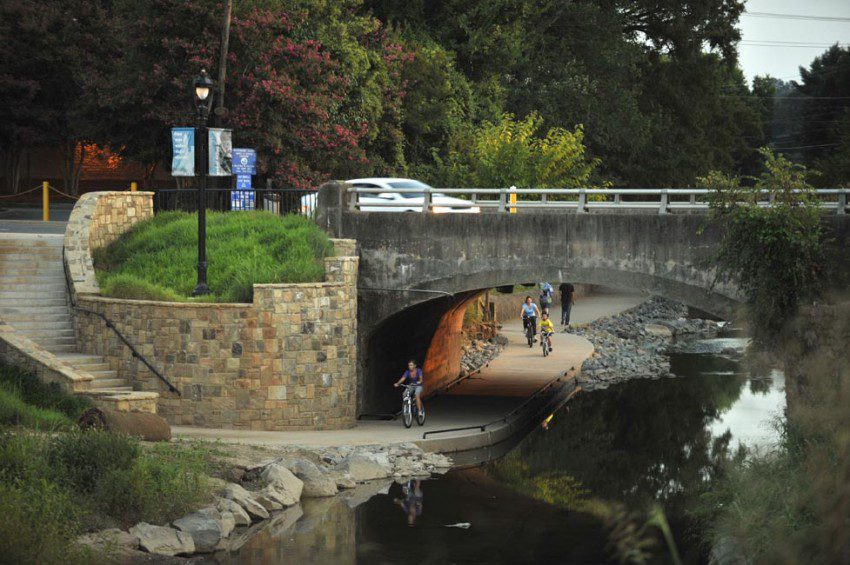

Little Sugar Creek Greenway passing under Morehead Street. Photo: Nancy Pierce

Still, the plan has drawn opposition from some neighbors, who say it’s too dense for the area — and worry about people parking on their streets and walking to the car-free apartments. They point out that there aren’t many grocery stores, restaurants or other services and amenities people often drive to within an easy walk, as in South End.

City planning staff don’t support the proposal in its current form, due to similar concerns about scale in the mostly single-family neighborhood.

Grubb and land use attorney Collin Brown pointed to other developments coming nearby, like the long-planned Savona Mill revitalization project, that will add more density.

There have been other halting steps towards car-free lifestyles in Charlotte in recent years. The city’s new transit-oriented development ordinance, adopted in 2019, set limits on the maximum allowed parking (instead of just the minimum required amount) for new developments near transit stations. That means other developers building projects along transit lines could use radically reduced parking amounts — or even eliminate parking altogether, if they choose — without special zoning exceptions.

And Charlotte is slowly dipping its toe into protected bicycle lanes. The city’s first, a one-mile pilot on Sixth Street in uptown, also opened last year. An extension of that pilot lane is expected to open in 2021, spanning the length of uptown.

Fixing past mistakes

One of the things some urbanists found so galling in previous eras was the way in which pedestrian-friendly features were cut from major infrastructure projects to save money. The prime examples of this were along the first leg of the Blue Line in South End, which opened in 2007.

A bridge extending the Rail Trail from South End into uptown was one of the key features that got the axe. That’s why you get dumped from a wide, pedestrian-only pathway to a narrow ramp and on-street sidewalk at I-277.

“The removal of the crossing left behind a critical link in the multi-use trail known as the Rail Trail, which runs between South End and Uptown,” Mecklenburg County commissioners said this week in an interlocal agreement they approved to fund part of the bridge. The project took another step forward with the county approval this week.

The $11 million bridge will be funded by the city of Charlotte, the N.C. Department of Transportation, the county and private sector donations. It’s expected to be built by late 2022.

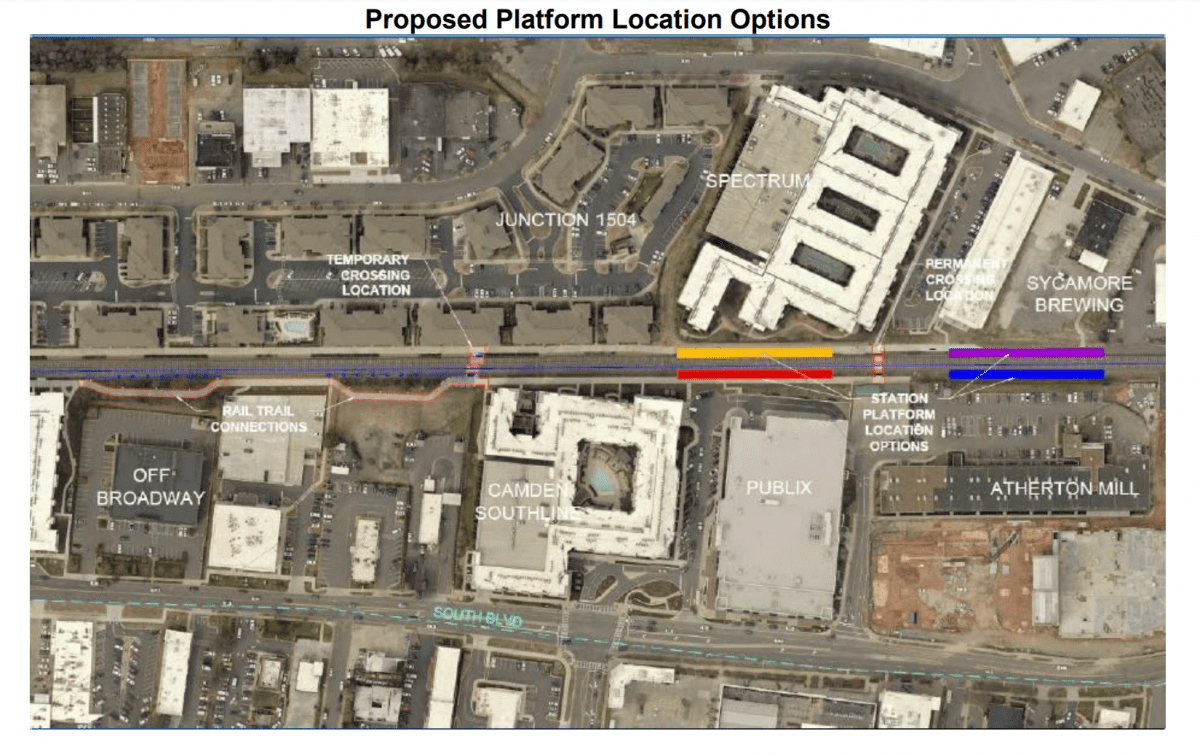

Charlotte Area Transit System

Another omission when the Blue Line was built: a station near Iverson Way, where there’s now a Publix Super Market and thousands of new apartments. With a mile in between stations, pedestrians have limited safe routes across the track. Leaders have been talking about a new station to fill in the gap for years, and the effort is slowly moving forward.

Charlotte Center City Partners is working to identify private funding to help advance the station (as with the Rail Trail bridge), and CATS has identified potential locations.

Experimenting with closing streets

This year, Charlotte finally went beyond temporarily closing streets to cars during the popular, one-day Open Streets 704 festival.

In May, the city closed two miles of streets near parks to through traffic (McClintock Road from The Plaza to Morningside Drive, Romany Road from Euclid to Kenilworth Avenue, and Jameston Drive/Irby Drive/Westfield Road from Freedom Park to Brandywine Road) to give people more space to get out safely while social distancing.

It’s a pilot program, but a spokesperson said Charlotte is still gathering feedback and looking at what streets could be opened to pedestrians next.

And the city has closed South Tryon Street to cars between Third and Trade streets to let people see and take photos with the new Black Lives Matter mural. The closure will go through at least July 10, and could be extended further.

Let’s say we were successfully able to close down Tryon St. to car traffic.

What kind of activation would you like to see?

What would you like to experience?

When you think of great cities, and your experiences within them, what about them leaves an impression on you? pic.twitter.com/GlxpDMUCVZ

— CLT Development (@CLTdevelopment) June 15, 2020

Taken together, there’s clearly been a lot of change in Charlotte’s attitudes towards cars, bicycles and pedestrians in recent years — at least in some small pockets. Is it enough to say we’re getting away from car culture anytime soon?

No. Some of the changes could be temporary, others are small and have been a long time coming. Other, less ritzy areas of the city are still waiting for basic improvements like sidewalks.

But in just the last few months, we’ve seen streets closed for the first time and a developer try to ban cars at new Charlotte apartments. So what does it add up to? Maybe the start of a different conversation for our next decades.

“Can you imagine if we had built this in South End 15 years ago?” said Brown, the land-use attorney, talking about the car-free proposal in west Charlotte. “That would have been fantastic.”