Charlotte leaders start wrestling with state transportation budget shortfall

Charlotte leaders say they won’t know the full impact of a nearly $12 billion funding shortfall for state road improvements until sometime next year, but a pair of projects in University City give a hint on what the funding gap might look like in concrete terms.

Think delays for needed roads, bridges and interchanges, plus more local money to fill the hole left by the N.C. Department of Transportation’s budget issues.

“The underlying issue of state and NCDOT budgets, unless and until that is addressed, we are going to be struggling,” said Charlotte City Council member Dimple Ajmera at Monday night’s strategy session. “This is coming from our local dollars. That’s really the state’s responsibility at the end of the day.”

As previously reported, the NCDOT’s estimates for the total cost of its 10-year transportation improvement plan has roughly doubled this year. Planners attribute the jump to a variety of causes, including rising materials and labor costs, legal settlements and early, inaccurate estimates that didn’t account for the true cost of inflation and land acquisition. The upshot is that North Carolina is facing an $11.6 billion hole for state road projects over the next decade – and that’s just for projects already committed to being built, not the total cost of future needed roads.

Earlier coverage: As projected construction costs surge, state road money dries up

In Charlotte, the state Department of Transportation owns and maintains roughly half the city’s major thoroughfares, including busy roads like Independence Boulevard, W.T. Harris Boulevard and Providence Road. Over the next decade, the state had planned to construct 78 miles of road improvements along those routes, costing nearly $3 billion.

But that’s all in question now. NCDOT officials are evaluating which projects to push back, which to break into phases, and which, perhaps, to drop altogether. Projects in the Charlotte region that haven’t already received state funding commitments, like improvements to I-77 south of uptown, aren’t likely to move forward until after 2033, city officials said Monday. And the projects that do go ahead are likely to face a lot of “value engineering,” a euphemistic term for chiseling away niceties like wider sidewalks and more aesthetically pleasing utility installations to save costs.

“With an $11 billion shortfall,” said Charlotte Department of Transportation Director Liz Babson, “we know the state’s going to have to make some tough decisions.”

But, she added, “we don’t anticipate knowing anything with any level of detail until early summer next year.”

In the meantime, local officials are planning for the shortfall as best they can with limited information. In University City, that means allocating $6.5 million of city money to improving the intersection at Claude Freeman Drive and West Mallard Creek Church Road – a state-owned and operated thoroughfare. As part of the plan, a private partner (Centene, the health insurance giant building a huge new facility in University City) will kick in another $7 million for the Claude Freeman intersection and a nearby interchange with I-485.

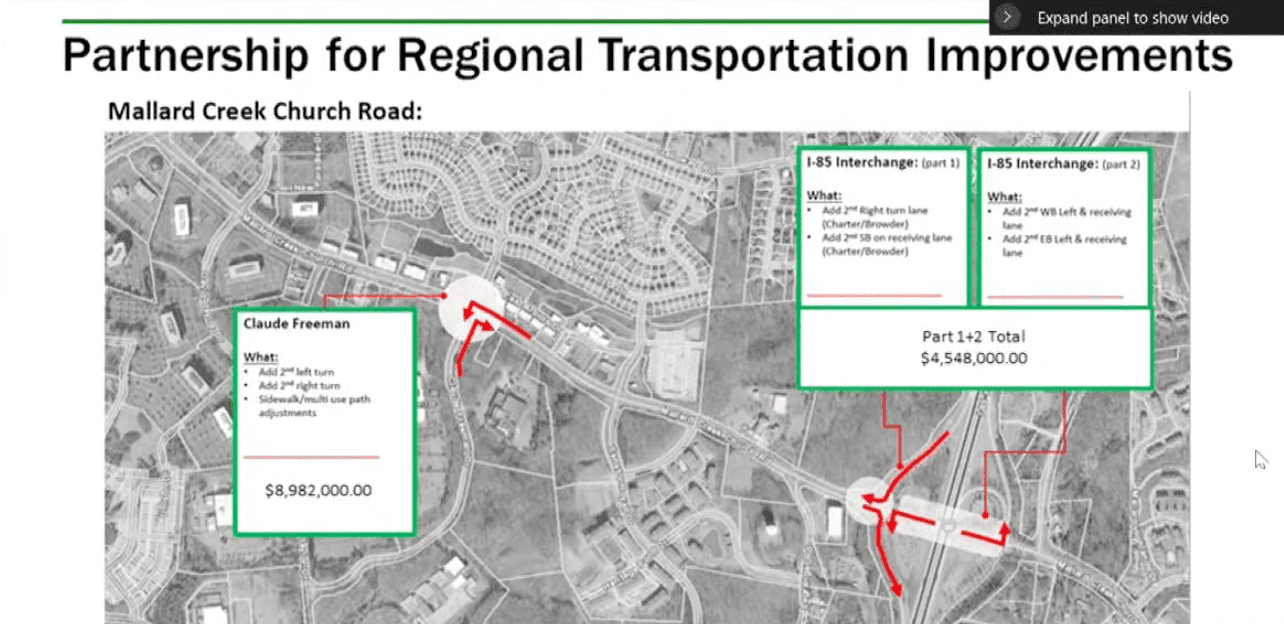

A slide from an earlier Charlotte City Council meeting shows two projects that would add turn lanes on Mallard Creek Church Road in University City. It’s a state road, but the city is proposing to split the $13.5 million cost with Centene Corp. to get the work done more quickly than the state will do it.

City planning staff said that pair of projects will serve as an example of how Charlotte can proactively use public-private partnerships to build local transportation infrastructure, without waiting for the state.

“The private sector’s taking care of something for us decades ahead of when the state could even potentially get to it,” said Tracy Dodson, Charlotte’s economic development director.

But some council members worry that the city is establishing a bad standard.

“So this is kind of a gift to the state?” asked council member Ed Driggs. “I’m a little concerned about the precedent, I guess, and about whether the state would perceive this as a reason to allocate other money away from us on the assumption that if it’s critical, we’ll figure it out.”

Council member Greg Phipps said that, given the NCDOT’s budget issues, Charlotte has little alternative.

“Unless we are content with living with the timeline of the state, which took I don’t know how many years to complete the I-485 around the city of Charlotte, I think that this presents a golden opportunity for us to partner, so as to not wait till perpetuity to get something done,” said Phipps. Companies like Centene and others can’t just afford to sit around and wait for something for as long as the state has.”

Although staff said they aren’t currently considering any comparable requests, expect similar discussions at city council in the coming months and years as the state works through its list of projects to trim, delay and cut while Charlotte tries to move forward. For example, the NCDOT is supposed to add express toll lanes and build other improvents on Independence Boulevard, and state officials have already said they’re looking at how to break the project into phases or reduce its overall cost.

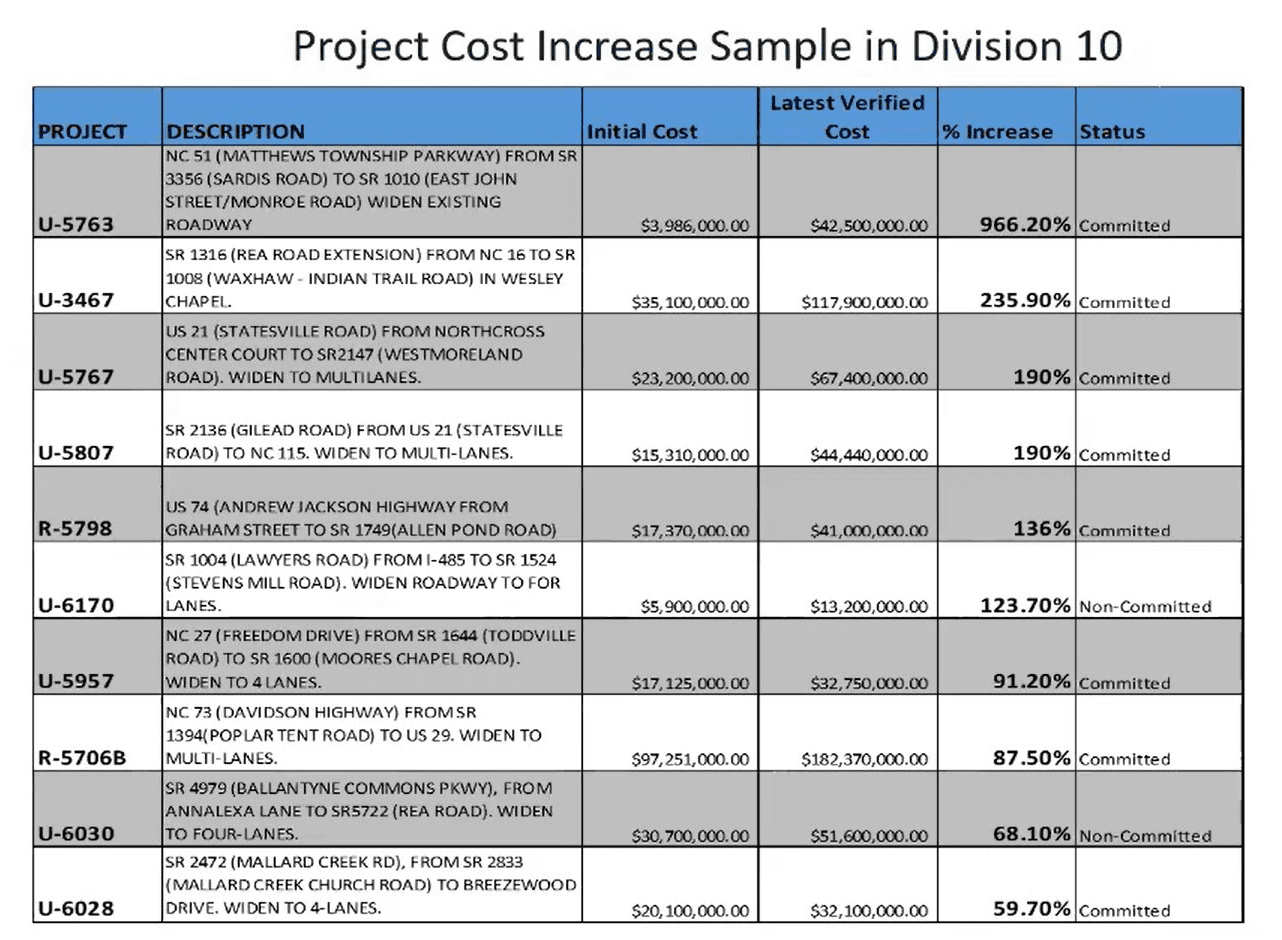

At a recent meeting of Charlotte-area transportation planners, an NCDOT representative shared examples of some of the surging cost estimates of local road projects, which rose between 59.7% (Mallard Creek Road) and 966.2% (Matthews Township Parkway).

At a recent meeting of Charlotte-area transportation planners, an NCDOT representative shared examples of some of the surging cost estimates of local road projects, which rose between 59.7% (Mallard Creek Road) and 966.2% (Matthews Township Parkway).

Estimates for many state projects have increased dramatically, ensuring more difficult discussions are coming. The widening of Matthews Township Parkway between Sardis Road and Monroe Road, initially estimated at $4 million, is now projected to cost $42.5 million, or a 966% increase; widening Freedom Drive from Toddville Road to Moores Chapel Road jumped from $17.1 million to $32.8 million.

Meanwhile, Charlotte is also seeking more than $13.5 billion to fund its local transit and transportation plans (the majority would come from a new 1-cent sales tax in Mecklenburg, with the balance from federal grants).

Mayor Pro Tem Julie Eislet said Charlotte is going to have to keep looking for its own ways to fund the infrastructure needed to accommodate the city’s growth.

“We’re not even addressing the fact that revenue is continuing to decline statewide,” she said, referencing the falling gas tax. “It’s fair to say that money’s not there. We can say it should be there, but it’s not going to come.”