Part 2: The relationship between design and transit use

In Part 1 of this series, I showed that there was a sharp increase in development since construction began on the Blue Line Extension in 2013.

Since then, there has been nearly $1 billion in new construction and 7,400 new residential units alongside the line. And despite the pandemic, demand for new construction has remained strong.

But what kind of development has happened since then? And will this new development encourage people to ride transit?

Where transit succeeds

NoDa and its surrounding neighborhoods have been a hot spot for new development for years, but developers have been mindful to incorporate the old town feel into new projects.

Historic properties, like the old Johnston Mill that’s under renovation, will add hundreds of apartments after sitting abandoned for years.

At Optimist Hall, designers were careful to preserve the century-old beams and flooring along with many other architectural details.

Some new developments emphasize walkability and alternative transportation. The Joinery, a six-story, car free apartment building is under construction in Optimist Park. The 83-unit complex is located near the Parkwood Station and will offer bikes, scooters and electric vehicles for rent.

[Read Part 1: How the Blue Line extension changed Charlotte development]

Going car-free may seem strange for a car-dependent city like Charlotte, but eliminating a parking garage is a tremendous cost savings that the developer says will be passed on to tenants.

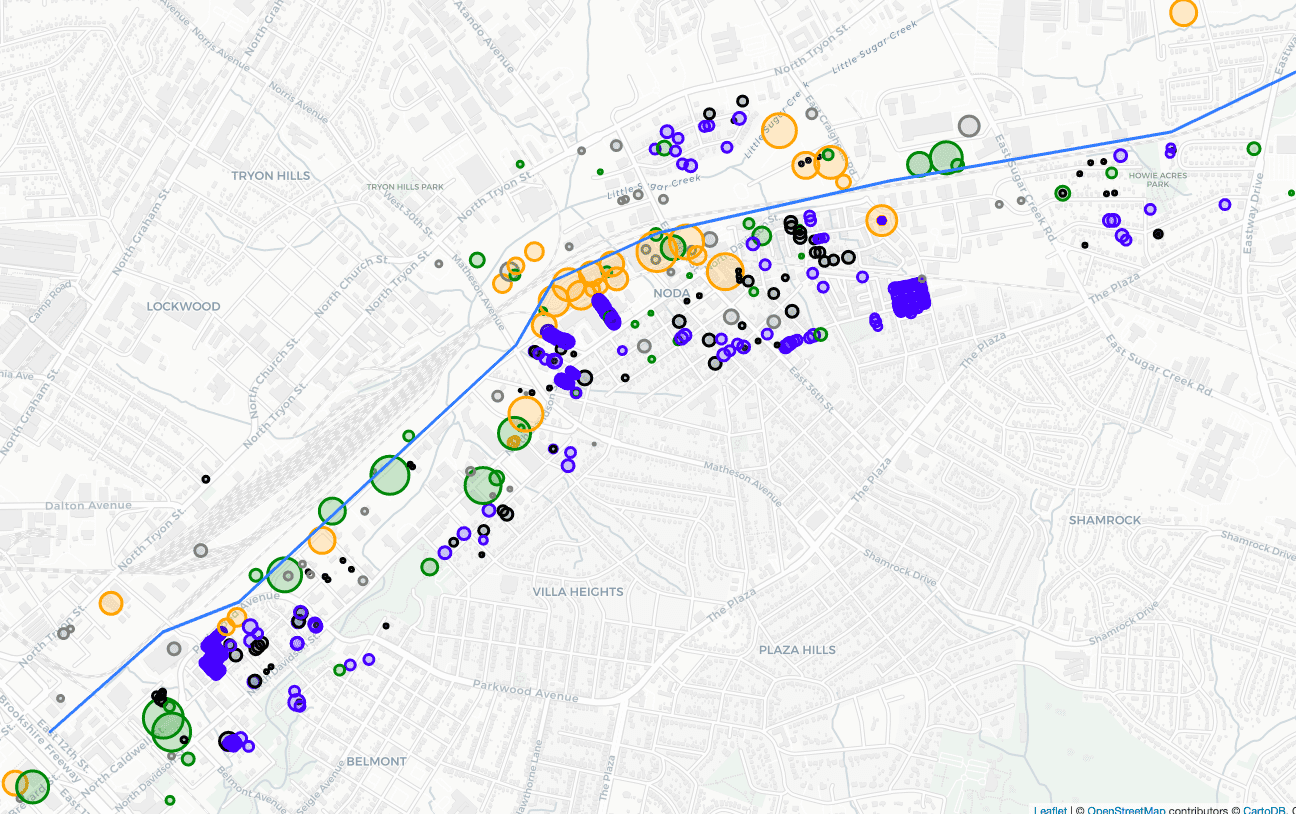

Developers are also taking advantage of transit oriented development zoning. Many of the highest density apartments (orange) and commercial buildings (green) are located adjacent to the light rail line. The map below shows both the category and size of projects along the BLE. Lower-density residential (blue) is typically further from the line.

All projects within ¼ mile of the blue line extension since 2013. Size of project indicated by the radius of the circle. Blue indicates residential, orange indicates apartments, green indicates commercial, black indicates demolition.

All projects within ¼ mile of the blue line extension since 2013. Size of project indicated by the radius of the circle. Blue indicates residential, orange indicates apartments, green indicates commercial, black indicates demolition.

Comparing aerial photography from 1960 to today, the traditional grid-pattern streets mostly remain unchanged. Infill projects have added density, especially around 36th Street.

But one of the largest transformations since then was the addition of I-277, which leveled entire city blocks and created a barrier to uptown.

Walkability and transit use

Walkability is a key determinant of public transit use. With its high density and large network of sidewalks, dining and historic buildings, NoDa receives a Walk Score of 80. That makes it one of the most walkable neighborhoods in Charlotte.

But much of Charlotte was constructed in the post-WWII era, and by extension, remains car centric and lacking critical infrastructure for pedestrians, making transit difficult to access by foot.

Charlotte’s is the sixth least walkable city in the US with a population over 200,000, according to Walk Score.

In the University Area, segments of the BLE run along the median of North Tryon Street. Traffic along this road is higher in volume and speed than in NoDa. According to the NCDOT, in 2019, the average annual daily traffic along this road was 26,000 cars.

Walking along this corridor can be jarring, unpleasant and sometimes dangerous.

In August of 2020, two pedestrians were struck by cars on North Tryon within minutes of each other. One died at the scene.

But walkability is not only a problem for the University Area. Many parts of the Charlotte area have a mobility problem. The Charlotte metro is ranked as the 34th most dangerous in the country for pedestrians.

At one time, there had been discussions of modeling the University Area around New Urbanism, which focuses on walkable streets, mixing uses, and accessible public spaces. But those plans gave way to isolated blocks of strip malls, suburban office buildings and single family homes.

Aerial photography shows that much of the land around UNC Charlotte was undeveloped in 1970, and that I-85 was under construction, but not yet completed. But since then the area has radically transformed.

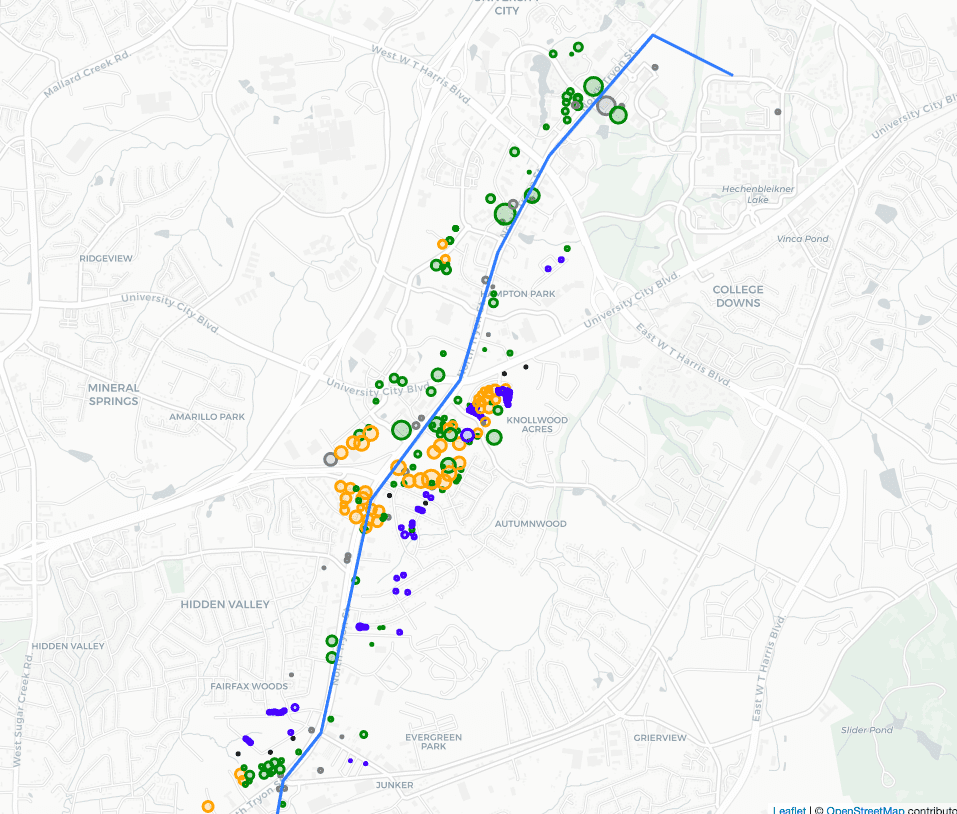

More recently, however, transit-oriented development zoning has encouraged higher density uses. Similar to NoDa, higher density projects are concentrated nearest to the light rail and some apartment projects are within walking distance to transit stations.

For example, Rush Student Living is a recently completed, 300-unit apartment building near UNC Charlotte. But getting to campus by foot requires crossing over the high-traffic, four-lane University City Blvd.

Many of the other new apartment complexes nearby are more disconnected and car dependent than in NoDa, and they lack critical infrastructure like interconnecting roads and sidewalks.

All projects within ¼ mile of the Blue Line Extension in University City and surrounding areas since 2013. Size of project indicated by the radius of the circle. Blue indicates residential, orange indicates apartments, green indicates commercial, black indicates demolition.

All projects within ¼ mile of the Blue Line Extension in University City and surrounding areas since 2013. Size of project indicated by the radius of the circle. Blue indicates residential, orange indicates apartments, green indicates commercial, black indicates demolition.

Other determinants of transit use

Density alone is not enough to promote transit use. A 2003 UCLA study found that the main factors predicting ridership were automobile availability, parking, economic factors, traffic congestion levels, density and the frequency and reliability of public transit.

The study sums up its recommendations by saying, “Policies which support private vehicle use – such as extensive arterial and freeway systems, relatively low motor fuel taxes, policy which require parking to be provided to satisfy all demand at a price of zero – affect transit use more than policies such as substantial public transit subsidies which encourage transit use.”

The venerable American urbanist and writer Jane Jacobs wrote that there were four conditions required to “generate exuberant diversity in a city’s streets”:

- “The district, and indeed as many of its internal parts as possible, must serve more than one primary function.”

- “Most blocks must be short; that is, streets and opportunities to turn corners must be frequent.”

- “The district must mingle buildings that vary in age and condition.”

- “There must be a sufficiently dense concentration of people.”

For people to choose walking over driving, streets need to feel safe; high traffic roads deter pedestrians. Parking lots and large empty blocks generate heat islands and make walking more difficult.

Imagining the future of the University area

The University City Area Plan adopted in 2015 calls for more walkability and connectivity.

Some of the main goals listed in the plan are to: “Accommodate higher intensity uses” and “Improve the accessibility and capacity of the transportation network.”

Some developers are also re-imagining existing spaces.

The Waters Edge development promises to transform a portion of J. W. Clay Blvd, adding more office and residential uses to the existing site. But it will still be surrounded by large parking lots and not directly adjacent to the JW Clay Blvd station.

In a recent virtual community meeting, John Howard, Silver Line TOD Study Project Manager, describes the TOD process as a mixture of mobility and access, land use, community design and equity.

“As we develop station area plans we want to make sure we have more…small blocks, connected streets, and a mixture of uses all around,” he said. “Early on, our consultants look at what we call a half mile walkshed, that is from the central area or station location we draw out that half mile radius, 10 minute walk area… then also looking at where those connection points are existing today and where we can fill in those connections with other streets and other important connections to get to and from the station areas.”

But he says that these things do not happen overnight, and developing along transit-friendly patterns in the suburbs might take more time to mature.

Even though much of the University Area is not a well connected and walkable place today, it’s possible that one day it might be. Accomplishing this goal will require city leaders to push for increasing density and connectivity. But the process could take decades.

Once areas become built out, it is very difficult to change the land use patterns. The grid pattern streets of NoDa work for pedestrians today, because they were built with pedestrians in mind. The best chance for walkability is to design for it before shovels hit the dirt.

The University City Area Plan is both strategic and optimistic. And though it could take years to come to fruition, it could radically change the character of the district.

Connectivity a key for future transit projects

City planners are considering the effect of low-density and high-traffic corridors on transit ridership, and they are accounting for that in the most recent proposed alignment for the Silver Line.

This future line will run from Charlotte Douglas, though Uptown and on to Matthews, and it eventually could extend to Gaston and Union counties.

Discussing the preliminary Silver Line route, Andy Mock, CATS’ senior project manager for the Silver Line recently said, “Incorporating light rail into Wilkinson Boulevard would create a very, very wide cross-section…It would almost double the width of Wilkinson Boulevard…[That would make it] hard to cross, and has major impacts on the businesses along there.”

That’s why the current plan calls for the Silver Line to run along, but not on, Wilkinson Boulevard.

But on the south side of the city, part of the line would run on Independence Boulevard, limiting the creation of high density development opportunities in those places. That is one of the challenges of balancing costs and feasibility with creating the most impactful community design.

Charlotte has ambitious plans for future transit projects — however, these projects are most effective when they encourage high density, walkable communities adjacent to transit stations. Charlotte has already taken a first step by approving the controversial 2040 plan that allows for duplex and triplex development in areas already zoned single family. Increasing density through TOD zoning, like the city did along the BLE, is necessary to increase transit usage.

Effective and efficient transit is key to the economic growth of the whole region. But as Jane Jacobs wrote, “Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.

Nathan Griffin earned a master’s degree in economics from UNC Charlotte in 2018 and a bachelor’s degree in business management from Pfeiffer University in 2016. He works as a project developer at Trane Technologies where he is involved in commercial construction projects. He also is an Adjunct Instructor of Economics at Central Piedmont Community College.

Nathan Griffin