Is this road design a better way to move, or an outdated solution for traffic?

As Charlotte grows denser and more urban, parts of the city built decades ago on an auto-centric, suburban framework are struggling to both absorb more traffic and adapt to new beliefs about how people should get around.

A one-mile stretch of congested road in fast-growing University City illustrates the tensions between balancing the needs of cars and pedestrians, as well as local residents and commuters, in an area where the distinction between urban and suburban is starting to blur.

Forty-thousand vehicles a day travel University City Boulevard, or NC 49. Many are commuters heading into Charlotte, north to I-485 or across the county line to Cabarrus. Thousands of students and workers also live across the street from the university, and walk or drive to class or jobs. But the pedestrian crossings that exist are wide, can take multiple light cycles to cross, and are spaced a quarter-mile or more apart. A worn groove in the grassy strip along the northbound side of the four-lane road shows how many pedestrians use the route despite the lack of a sidewalk for long stretches.

The NC Department of Transportation has a plan to fix the road: Widen NC 49 from just north of UNC Charlotte at John Kirk Drive to I-485, to six lanes either way. They’re planning to use a design formerly called a “superstreet,” but now referred to as “reduced conflict intersections,” that will limit left turns and crossing traffic, making for smoother traffic flow and more green lights for drivers.

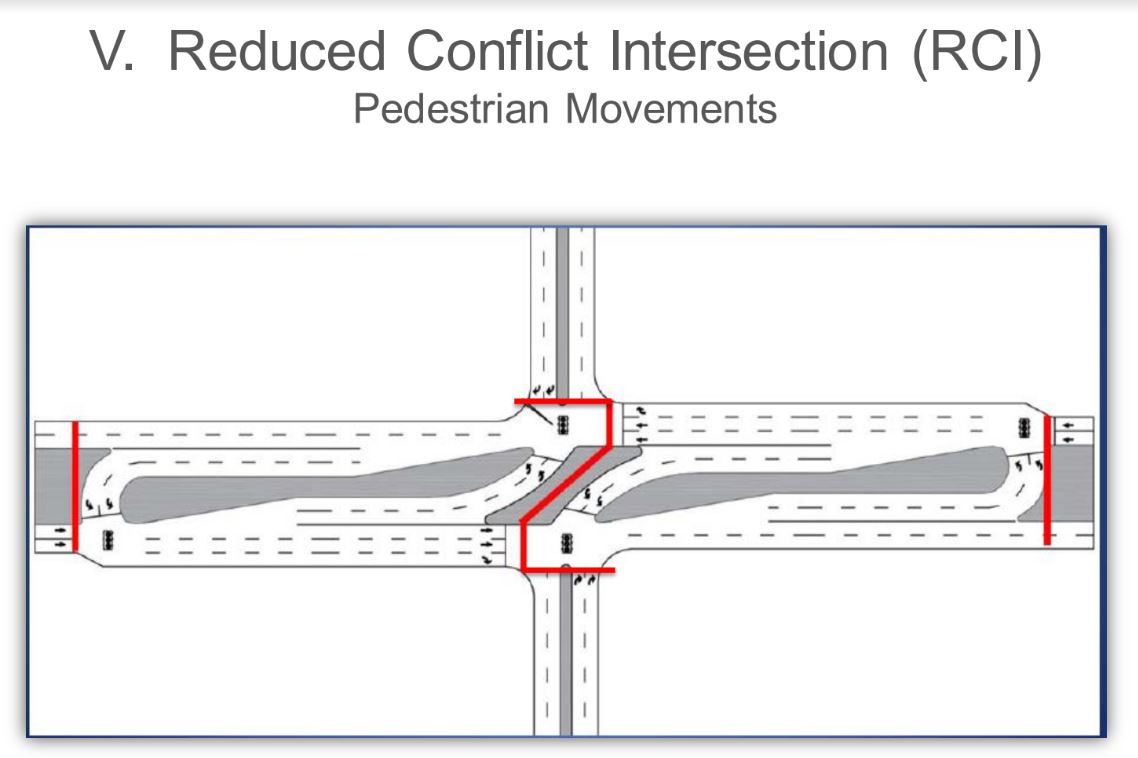

“What the RCI concept allows you to do is reduce the number of conflicts, which allows traffic to flow better,” said project manager Wilson Stroud. For example, at intersections like John Kirk, drivers would no longer be able to go straight across NC 49 or make a left turn. Instead, they would turn right, then make a U-turn in a designated turn lane.

The NCDOT plans call for 12-foot pedestrian and bike paths on either side of the widened road, as well as realigning Back Creek Church Road and closing the at-grade railroad crossing located there. The $42 million plan is funded, with construction to start in 2023 and wrap up three years later. Planning and environmental work is currently underway.

The NCDOT contends the wider road will be both faster for drivers and safer for pedestrians. But the idea of building a wider road to accommodate thousands of more vehicles per day in a fast-densifying area has drawn skepticism from some quarters.

“It is a just-fine solution for a lot of other places, particularly in high speed corridors in rural areas,” said Tobe Holmes, planning director for University City Partners. “But it completely forgets the rest of what we’re trying to do here…We’re trying to urbanize this thing and have people cross the street.”

To the west, on the other side of the UNC Charlotte campus, the Blue Line light rail extension now runs up North Tryon Street. Advocates and local planners have pinned much of their hopes for denser development on the transit line spurring greater walkability and luring people out of their cars.

The two modes of transportation development – light rail on one side, widened highway on the other – create a sharp contrast.

The sidewalk on the northbound lanes of NC 49 abruptly ends north of John Kirk Drive. Photo: Ely Portillo

“Design drives land use,” said Holmes. He also worries that the six-lane widening will continue south down NC 49 towards North Tryon Street and the light rail corridor, as increased auto capacity to the north creates a bottleneck when NC 49 narrows back down to four lanes.

“It would be OK if we knew it’s going to stop,” said Holmes. “It’s not going to stop. That’s where a lot of the anxiety comes from.”

A future widening project for the next stretch of NC 49 is included in the NCDOT’s plans, but hasn’t been funded. The plan could be considered in future years.

University City isn’t the only place around Charlotte where a “superstreet” is proposed. The NCDOT is considering a similar design for widening NC 73 from NC 115 to Concord Parkway, through Mecklenburg and Cabarrus counties.

The design has drawn opposition in some locations, as transportation officials try to balance the needs of increasing vehicular traffic, pedestrians, local residents, commuters and businesses.

The Boone Town Council rejected plans for a similar road widening on NC 105 earlier this month, according to the Watauga Democrat, citing concerns from residents. And Matthews is seeking a delay to the planned widening of John Street through its downtown, after the NCDOT already agreed to scale down the “superstreet” concept and move to a more conventional design.

“Our residents want to see Matthews remain a small, friendly town with historic charm, and a welcoming and walkable downtown area,” Matthews mayor Paul Bailey said in an statement.

Similar goals, opposite approaches

Both the NCDOT and advocates like University City Partners have similar stated objectives: Improve a congested road and make it easier for pedestrians and bicyclists to get around. And neither contends that the road is working well, as currently constructed.

Source: NCDOT.

There have been more than 800 crashes on the road over the past five years, Stroud said, and NC 49’s crash rate is about four times the statewide average. There were also eight pedestrian crashes, including one fatality.

“We’re providing more crossings and they’re closer together,” said Stroud. The widened road would have six signalized pedestrian crossings instead of four, and they would be a maximum of 1,100 feet apart, instead of the current 2,000-foot distance, and will provide pedestrian refuges in the median. The sidewalks also wouldn’t abruptly end.

“We feel like that will help encourage bicycle and pedestrian activity,” said Stroud.

Holmes said he fears the wider road and unconventional design will create a “massive moat” that deters pedestrians and locks the corridor’s auto-centric design in place. To cross from one side of an intersection to the opposite corner could require pedestrians to cross the street four separate times, even though each crossing would be shorter in length.

“There are a lot of other solutions,” Holmes said, including building out more of a road network so people have alternatives to congested arterial roads. “It’s not as black-and-white as just building a bigger road is. It’s building out a network.”