Some suburbs facing the dilemma of high growth vs. low taxes

In cities and counties surrounding Charlotte and Mecklenburg County, tensions are swirling over the rate of new residential development, what it should look like and – especially – how to pay for it.

Those aren’t new challenges in a metro area that’s been one of the nation’s fastest growing in recent decades. But many communities, still financially tender from a hard-hitting recession, are caught in a predicament.

In fact, some officials say they’re at a complicated crossroads that could well determine the future quality of life in their communities, where rapid growth is fueled by access to jobs and urban amenities available in Charlotte.

“It’s a difficult situation,” says Lancaster County (S.C.) Council member Brian Carnes, who represents the unincorporated area known as Indian Land, where much of the growth in his still mostly rural county is happening – just south of Charlotte’s affluent Ballantyne area.

|

“There is a big disconnect between the service level we can provide with the taxes people want to pay.” — Lancaster County (S.C.) Council member Brian Carnes |

“We can meet the basic demand,” he says. “The problem is meeting the expectations. We get people comparing what they see in Charlotte. There is a big disconnect between the service level we can provide with the taxes people want to pay.”

Ironically, it is the promise of low taxes, houses spread out on large lots in nicely landscaped neighborhoods and strong schools that attracts families to areas just outside higher-tax cities like Charlotte. But many new residents, though hoping to dodge the higher costs of city living, want city-level services – without paying the taxes that cover the price tag.

“Everyone wants to get to heaven, but not everyone wants to go to church,” says Bill Deter, mayor of Union County’s Weddington, just across the county line from Charlotte and one of the wealthiest towns in North Carolina. “You either have to reduce services or increase taxes. We have to communicate to voters what the tradeoffs are. Raising taxes is the action of last resort.”

Beyond the distaste for higher taxes, communities are polarized between the needs and desires of rural areas and urbanizing communities. Construction has started on hundreds of homes that were approved before the 2008-09 financial crash, and still more new developments have been approved or proposed, many featuring multifamily projects.

Services are being strained as demand increases for fire trucks and police, water and sewer expansion, more classrooms, streets and roads. Officials struggle with whether to raise taxes and fees. And residents are protesting decisions they don’t like, sometimes with lawsuits.

“There is no way of getting around the fact that if you grow as fast as some of these communities, you have to pay for it,” says Bill McCoy, director emeritus of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute and a longtime observer of regional growth patterns. “There is a conflict between people who have lived somewhere a long time and people just moving in. Anytime there is talk of an increase in taxes, there is a kickback, because some areas think they don’t get anything.”

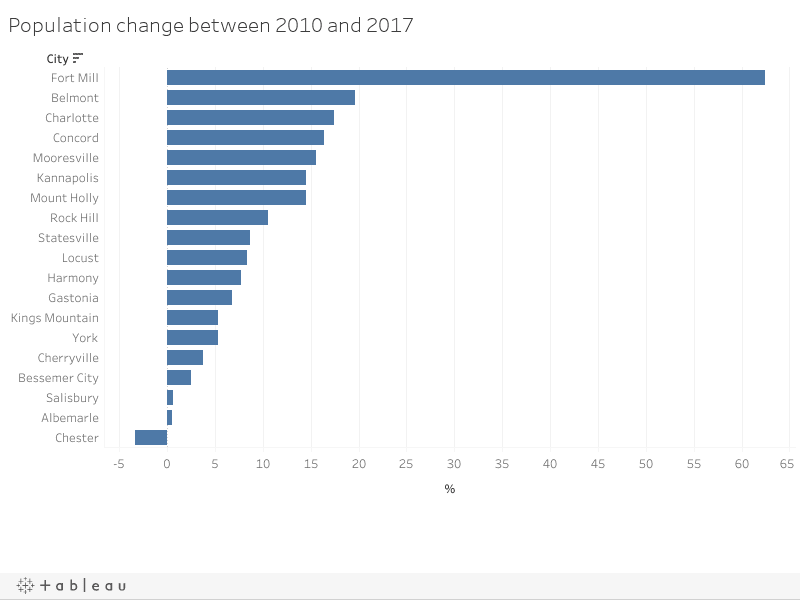

In the next 20 years, the two-state Charlotte region’s population is projected to grow by 50 percent, and in 40 years to double. A tour around the area reveals how communities with varying regulations and policies grapple with the challenges and costs of growing urbanization.

Union County

Interactive DashboardsClick here or scroll to the end of the article for interactive dashboards on residential building permits and population growth in Charlotte region counties. |

Disgruntled county voters last month ousted the school board chair, who had led a controversial redistricting plan to ease overcrowding in Indian Trail, Weddington and other areas near Mecklenburg County – whose school district has angered parents for years with redistricting to accommodate growth. Some Union County residents are angry, again, that another redistricting is planned for elementary students who move into sections of a Waxhaw neighborhood under construction. School officials say they must adjust to the new development. Residents complain they believed there would be no assignment changes for several years. Click to scroll below to dashboards of regional building permits and population.

How schools cope with explosive growth has been a roiling issue in Union County. Under state law, county commissioners pay for school construction. Union school board members and county commissioners have disagreed on how to finance new schools and rising expenses. The school board last year sued the county commissioners for more money and won a $91 million verdict. It’s under appeal.

To cover school district costs, last summer the Union County commissioners approved a 15.4 percent property tax increase, from 66 cents to 76.14 cents per $100 of property valuation for the 2014-15 fiscal year. It was the county’s first property tax increase since 2007.

In Wesley Chapel, another municipality near Mecklenburg, resident Kim Hillegas says she’s disappointed in how officials are managing school issues. “The state needs to quit catering to developers,” says Hillegas, who moved from Arizona nearly two years ago and helped lead the group that sued unsuccessfully to block the redistricting. “We have an extremely powerful homebuilding lobby who have been able to convince officials they should not help pay for schools.”

After years of rancor between homebuilders and fast-growing counties, the N.C. Supreme Court in 2012 struck down efforts by local officials around the state to either require or prod developers to pay fees to help fund school construction. Developers say the fees are illegal and raise housing costs. They say local officials have another option: raising property taxes to pay for school expenses.

As with schools, housing growth has also stretched the capabilities of Union County’s water and sewer operations.

In June, officials approved a water tower in Weddington after a seven-year debate during which residents argued the tower would be an eyesore, hurt property values and cost more than underground storage. This year’s county budget calls for a 6.5 percent increase in water and sewer rates each year for the next few years to pay for systemwide maintenance and improvements. Union operates the largest-county-run water and sewer system in the state; most systems, such as Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s, are operated by municipalities.

“Union County,” says McCoy, “is the perfect storm.”

Lincoln County

In Lincoln County, across Lake Norman from Mecklenburg, a 1,650-unit development near the lake planned by Arizona-based Shea Homes is likely to ignite vigorous growth in a rural county of fewer than 80,000 people. Targeted at residents ages 55 and older, It will be the county’s largest subdivision.

Property tax rates in N.C., S.C. |

In addition, a 116-acre mixed-use development with 220 single-family homes, 240 apartments and commercial development has been proposed for N.C. 16 in the unincorporated Lincoln County community of Denver. Construction is also underway nearby on a 385-single family subdivision formerly stalled by the recession.

“There’s a lot going on,” says Planning Director Andrew Bryant, describing Lincoln County as the region’s “hidden gem.” In 2013, Lincoln had a larger percentage increase in residential building permits from 2012 than any other county in the region.

Bryant anticipates pressure for more development after the completion of the northeast leg of Interstate 485 in Mecklenburg, which would improve commuting options for Lincoln County residents.

“With this growth coming, we’re starting to look at our water and sewer capacity,” he says. “We’re trying to jump ahead. We don’t want to be caught off guard. We’re just trying to make sure we maintain a sustainable pace of development.”

Bryant says a county study projects that tax revenue from residential development over the next few years will pay for expanded services, primarily because the new senior community won’t affect schools. For the long term, he says, “We’re moving forward cautiously. We don’t want to be victim to the same mistakes that others have made.”

Lancaster County, S.C.

In the rapidly urbanizing Indian Land area in Lancaster County’s Panhandle, South Carolina’s lower taxes and proximity to upscale Charlotte neighborhoods have sparked a growth wave that officials are racing to control.

“It’s almost like a tale of two cities,” says County Administrator Steve Willis. “Indian Land has been growing like blockbusters, but the rest of the county has not been growing much.”

Indian Land residents have no paid fire service, relying on volunteers. There is no police department; the area is patrolled by county sheriff’s officers. Some residents complain they can’t get snow plows to clear residential streets and sidewalks.

But residents in the county’s more rural areas reject any idea of spending more public money.

Lancaster County Council members this year raised taxes and some fees in a narrowly approved 2014-15 budget, with some officials worried about demands on future spending.

And after years of controversy, officials also narrowly adopted a zoning overlay district for the Indian Land area that sets aesthetic requirements for new construction, such as sign placement and landscaping. But shortly after it was passed, County Council members deleted some requirements.

“There are growing pains,” says Planning Director Penelope Karagounis. “This county is going to have a challenge trying to pay for all the new services.”

York County, S.C.

While most S.C. border communities near Charlotte are growing rapidly with residential development, a 2007 state law exempts owner-occupied houses from paying property taxes for school operations.

That means, some officials say, that all the new houses strain schools but don’t help pay for the expanded school services they require. The state’s commercial and industrial properties cover the cost of school operations, while residential taxes pay for debt owed on school bonds.

Some members of the York County Economic Development Board have suggested that officials consider limiting residential development along the Interstate 77 corridor to make room for businesses. They have asked officials to develop a countywide plan clearly defining land for residential and business and industrial development.

In York County, most new growth is concentrated in Fort Mill and unincorporated areas near Charlotte. Some Fort Mill residents have complained about runaway growth and want new restrictions. Recently, plans for nearly 400 townhouses in two developments attracted loud opposition from residents. The Town Council approved the projects in July.

York County Council members recently delayed until 2015 a decision on whether to amend a zoning overlay for parts of Lake Wylie. The controversial proposed changes called for stricter guidelines on density and open space requirements from the Buster Boyd Bridge at the N.C. line to Three Points along S.C. 49.

Some officials said they feared the proposed changes, which could have slowed development in the popular unincorporated area, would generate lawsuits. Residents fiercely opposed the proposal, saying it would unfairly restrict the use of their property. Officials agreed to more study and will begin public meetings next year for a more comprehensive growth plan.

Connect Our Future

Meanwhile, in an initiative started 2 ½ years ago and funded through a federal grant, residents and officials from 14 counties in North and South Carolina have come together to reach consensus on a regional growth framework to serve as a blueprint for local growth policies.

“This is a manifestation of people’s ideas on what growth should look like,” says Michelle Nance, planning director of the Centralina Council of Governments, which represents Charlotte-area counties in North Carolina and is coordinating the effort with the Catawba Regional Council of Governments in South Carolina. The regional growth framework calls for such priorities as creating mixed-used centers and walkable neighborhoods as well as more housing and transportation choices and open space.

The CONNECT Our Future initiative does not address how to pay for services and the other demands of growth, although a county-by-county analysis is being developed that indicates which types of land use patterns would better pay for themselves.

The success of the planning effort, however, depends on whether local officials integrate those concepts into local development decisions on managing growth – and how to pay for it.

Disclosure: The UNC Charlotte Urban Institute, which runs PlanCharlotte.org, has a contract with the CONNECT project to develop a set of regional metrics to track progress over time and to house those metrics on a page on the institute’s website. Institute Director Jeff Michael and the institute’s researchers working with CONNECT had no role in writing or editing this article.