Would closing these streets help our lack of public space?

A steady rain of giggles falls on a busy street in uptown Charlotte. A neat row of seesaws undulate back and forth, bright LED strips highlighting their movement, as elated, carefree riders push off. The smell of food trucks serving eager patrons wafts through the air.

Parents watch, relaxed, knowing they don’t have to pull their child out of oncoming traffic, as kids run about.

You stop to marvel, and think: “Why isn’t it always like this?”

What’s most amazing about this scene is that it’s not in a park, or a playground. This experience was created in the middle of Levine Avenue for the Arts in May 2019.

For a city that prides itself on its lush tree canopy, Charlotte is notoriously lacking in public space to enjoy those trees. Urban growth is snapping up potential parkland faster and faster, with developers willing to pay premium prices to get in on the action.

The public space mentioned above sounds fanciful, but it happened during Charlotte Shout, part of the #CLT250 celebration marking the city’s sestercentennial. Once the celebration was over, the seesaws were packed up, the barricades removed, the street surrendered back to the automobile.

I don’t think that should have happened. Here’s why, along with two other candidates for the removal or reduction of car access in Charlotte:

The No-Brainer

South Tryon has become the new cultural nexus of Uptown, but it lacks a signature gathering space. While The Green is a beautiful space, it’s not very versatile. A good space can be adapted, and #CLT250 proved that few places are quite as adaptable as Levine Avenue for the Arts.

By closing this lightly used thoroughfare to cars, you could create the “Levine Cultural Square,” complete with permanent and rotating art, experiential placemaking opportunities and places where local and national brands can engage with people. The approximately 1.25 acres of street and sidewalk space spills onto South Tryon, and if you designed it with a clever decorative connection you could tie together The Green and the new pedestrian arcade planned for Duke Energy Center 2.

With the impending closure of Marshall Park, it would also open up a new space for quiet reflection, as well as political action. Placed in the shadows of some of the city’s greatest cultural assets — Knight Theatre, Gantt Center, Mint Museum and the Bechtler — it’s the easiest space to make happen.

Curious about what it would take to close a street for good, I spoke with Charlotte spokesperson Scierra Bratton:

“Any modifications to the street network require a thorough analysis of the impacts to vehicular traffic, transit, access to adjacent properties, displacement of curb lane activities (loading, delivery, etc) and where these activities would ultimately occur. Extensive community engagement around impacts and trade-offs would be required along with community buy-in for the proposed changes.”

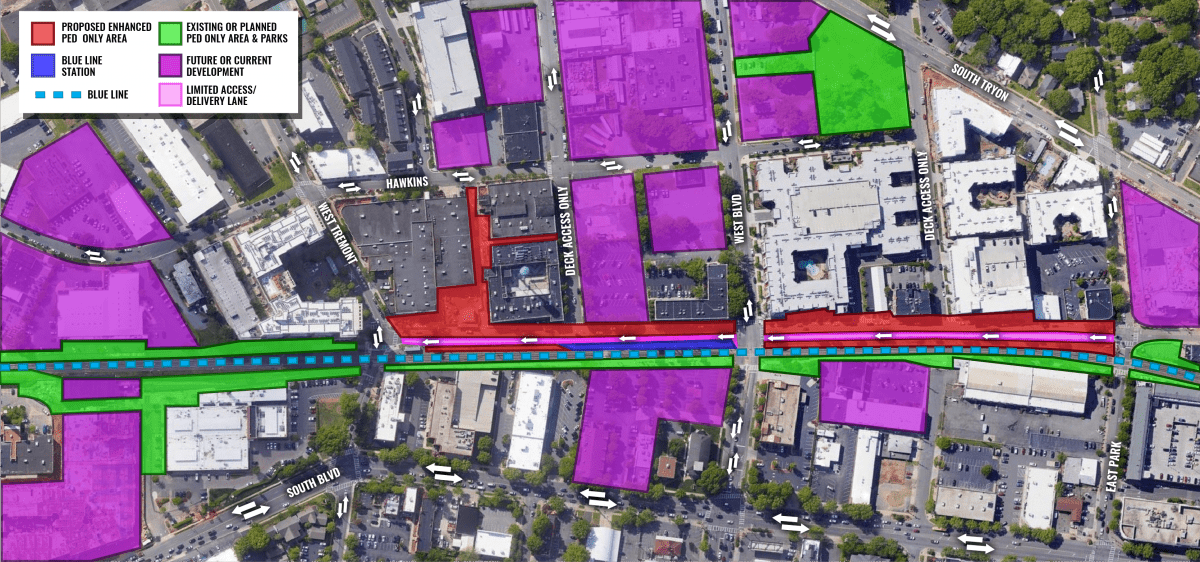

The Rail Trail Enhancement

The Rail Trail is the most exciting piece of pedestrian infrastructure in Charlotte. Some of the most creative minds in the city are responsible for shaping it, and the trail is constantly maturing. But significant gaps still exist, and the most glaring missed opportunity is the space between East Park Avenue and West Tremont.

Over the past few years, Camden has undergone quite the transformation. The buildings are taller, the tenants have changed and more people than ever live or work there — yet most of the pedestrian infrastructure looks exactly the same. With the exception of the sidewalks in front of Camden Gallery and 1616 Center, most buildings still have their small sidewalks, edged with grass strips facing Camden.

Megan Liddle Gude, Director of South End who spoke glowingly about all the positive community responses to OpenStreets704, a sponsored event held by the city a few times a year, where certain city streets are closed to cars, and opened for public recreation, exercise, and experiences. But she noted that whenever the city closes down streets prior to an event, the neighborhood receives complaints from businesses about a drop in customers during setup.

I think Gude’s point is valid, but it’s becoming a less viable argument. Camden is growing toward critical mass and it won’t be long before thousands of workers, residents, and even hotel guests will be within walking distance. With South End becoming such a valuable stroll district, we should foster and enhance the experience. If you could get new developments like Lowe’s technology center and tower and Stiles to set aside some of their after-hours parking for the public, you could support the area even further.

Christchurch, N.Z. Photo courtesy CLT Development

To transform Camden, you could start by leveling out everything from from the sidewalk to the Blue Line berm. With everything the same grade, you could then encourage walkers, runners, scooter riders, and find creative ways to limit car traffic. I would recommend making Camden a single lane going Southwest, instead of the current two-way, divided traffic flow.

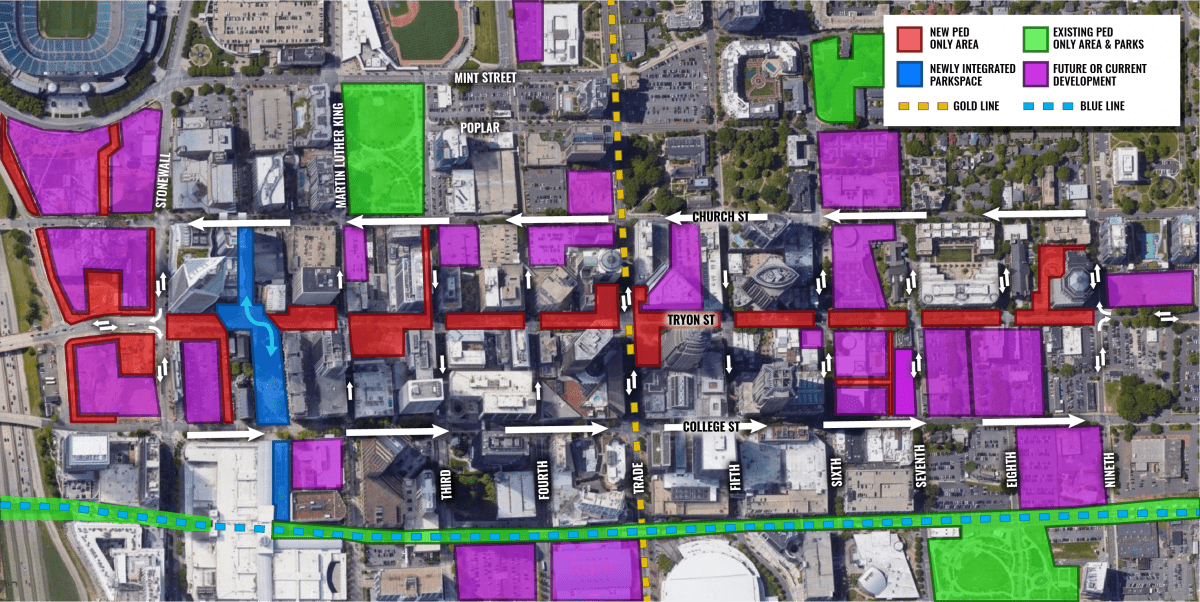

The Game-Changer

Advocacy for closing Tryon Street to cars, from Stonewall to 9th, has reached almost a fever pitch — at least on Twitter. In theory, it could work: Church and College streets could handle a lot of the two-way traffic that would be diverted, and the cross streets would still stay active.

My main concern is that Tryon has not yet been built out enough at the pedestrian scale for this change. There are still far too many entrance-less expanses on building facades, blank lobbies and reflective glass walls. I would concentrate on converting the street fronts before closing it down to car traffic.

Michael Smith, President and CEO of Charlotte Center City Partners, advocated a gradual approach:

“As we consider how to create people-first places, we know there is much distance between today’s built environment and an auto-free street in Center City. There are moves we can make, shy of permanently closing streets, to create more welcoming spaces for pedestrians. We have seen the positive effects of lane diets, bulb-outs and temporary street closures for events such as Open Streets 704, Charlotte SHOUT!, and Art & Soul of South End. We also know the incredible value of great public spaces such as plazas, parks, and the Rail Trail. We believe that a multimodal environment that is balanced among uses is the most powerful and of greatest service to our community.”

With these three Charlotte ideas in mind, let’s take a look at three case studies from around the world, and what types of spaces can be created by reducing automobile access, or removing them altogether.

Charlottesville Mall. Photo: David Lepage, city of Charlottesville publicity package

The close-by small town: Charlottesville Mall

In 1976, Charlottesville, Va., underwent a process that was truly novel for the time. City leaders closed eight blocks of their downtown to car traffic. Only cross traffic is allowed, creating eight individual “urban living rooms,” with places to sit, dine, attend theaters and entertain oneself. It’s a stunning and successful public works project for a city with 800,000 fewer people than Charlotte.

The area has urban homes looking out on soaring willow oaks. You’ll find brick pavers, wayfinding, art, fountains and tons of greenery. Its terminus spills into an amphitheatre that hosts national touring acts, food and wine festivals, pride, and tons of other events. This is the kind of experience that makes a city great for visitors, workers and residents alike.

A street in Montreal. Photo: Clayton Sealey

Success across the border: Rue Prince-Arthur, Montreal

The first place I really fell in love with the pedestrian street was Montreal. The Canadian city is arguably the most European city in North America. In places, it retains a French and English charm, instantly transporting you across the ocean.

What struck me though, walking around, was just how often I was on pedestrian-focused streets. My wife and I zipped across Montreal on foot, encountering one after another. Our favorite was Rue Prince-Arthur, which bisects a popular neighborhood for five blocks, spilling out into Square Saint-Louis.

The street, which was closed back in 1981, has seen its ups and its downs in popularity. At one point it was so packed with people, it was to be avoided. As Montreal has gained more seasonal and permanent pedestrian streets, it has gotten much quieter. In spite of this, the street remains attractive, innovative and full of attractive public spaces for the community.

Christchurch, N.Z. Photo: Wikimedia

The intermodal superstar across the globe: CIty Mall, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Creating successful pedestrian spaces is about creating something truly intermodal. The most memorable places will include space not just for pedestrians, but for mass transit. Cashel Street in Christchurch, N.Z., has tons of urban retail and restaurants, shade trees, planters and greenspace. Within this intimate pedestrian space, there is no room for cars — but they carved in a space for a heritage streetcar. The road really prioritizes alternative modes of transportation and only grants vehicles access for deliveries, fire, and police.

The pedestrian streets (High, Oxford Terrace and Cashel) that comprise the City Mall were first closed to car traffic in January 1982, and opened back up for pedestrian only use by that same August. The area exploded with growth until 2010, when the devastating Christchurch earthquakes hit, leveling buildings, and leaving the once thriving area, on the verge of ruin. The city rebounded, replacing demolished buildings with shipping container retail, until it was restored once again with brick and mortar retail buildings.

Texturally, it’s the perfect analog for how I’d like to see Camden reimagined.

CLT Development is a social media account that covers, explains, and occasionally critiques commercial development in Charlotte, while fostering and leading discussion about urban planning/transit/city building initiatives. It is managed by Clayton Sealey, with the help of contributors.

Clayton Sealey, CLT Development