Gaston County: An Introduction

Introduction: If a county in the Charlotte region could be classified as a sleeping giant during the past two decades, it would have to be Gaston. After roaring to prominence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as the center of the region’s ascendant textile industry, and emerging from that period as the region’s second most populous county behind Mecklenburg, Gaston’s growth cooled during the last half of the 20th century. While similarly situated counties in the region, such as Cabarrus and York, took advantage of their proximity and easy access to Charlotte to transform themselves into thriving suburban communities, that rapid growth seemed to bypass Gaston County while its textile mills continued to provide steady, albeit low-wage, employment opportunities for the county’s citizens. Only recently, with the dramatic decline in the county’s textile industry, has Gaston shown signs of awakening to its untapped potential as a significant player in the Charlotte region’s new economy.

Historical overview: An excerpt from: A Guide to the Historic Architecture of Piedmont North Carolina (UNC Press), Catherine Bishir and Michael T. Southern. (p. 477)

“Known as “the combed yarn capital of the world,” Gaston saw more textile mills than any other county in the nation – over 150 established between 1848 and 1950. The county was largely agricultural, however, from the mid-18th-c. settlement well into the 19th c., with Scotch-Irish farmers settled along the Catawba, Germans along the South Fork and around present day Mount Holly, and English and Africans. There were a few streamside mills and some iron, tin, and gold mining, the latter attracting Italian and Irish Catholics among the miners and leading to the formation of the state’s first Catholic churches and thence to other major Catholic institutions (St. Joseph’s, Belmont Abbey). When the county was formed from Lincoln in 1846, it was named for William Gaston, supreme court justice from New Bern and Catholic lay leader (d. 1844).

In the mid-19th c., industrialization built the first textile mills on the great rivers, beginning with Mountain Island Mill on the Catawba (destroyed by the flood of 1916), established in 1848 as an outgrowth of Greensboro’s Mount Helca Mill. Adding good rail connections to reliable water power, enterprising descendants of Scotch-Irish and German settlers made Gaston a national textile center. When the county seat of Dallas rebuffed rail connections, Gastonia began in the 1870s on the Atlanta & Charlotte Air Line Railway, grew fast, and won county seat status in 1909. First on the Catawba and its tributaries, then beside the railroads, Gaston’s mill communities constituted much of the textile “state” surrounding Charlotte, and Gaston’s factories embodied early advances in technology, including electric lights at McAden Mill and air conditioning at Chronicle Mills. Some industrial sites remain in Lowell, Bessemer City, Ranlo, and Spencer Mountain. Although many mills have been razed, important textile architecture survives, along with farmhouses and county churches from the agricultural past.”

Gaston today: Of all the counties bordering Mecklenburg and connected to it by an interstate highway (Gaston, Cabarrus, Iredell, and York), Gaston stands out as having benefited the least from its proximity and easy access to Charlotte during the past two decades of regional growth. Given the jump-start Gaston had on those other three counties in terms of industrialization during the first half of the 20th century, it may come as a surprise to see how quickly the other counties were able to catch up with Gaston economically. Looking at population growth alone, Gaston was the second largest county in the region behind Mecklenburg in 1950, with its population of more than 110,000 outpacing its closest rival among the other three (York) by nearly 40,000 people. By 2009, York was on its way toward surpassing Gaston in population, with an annual growth rate of around 3.2% compared to Gaston’s 1%, while Cabarrus and Iredell were rapidly catching up, with annual growth rates of 2.2% and 1.6% respectively.

There are several possible explanations for Gaston’s slower pace of growth during this period. Some have suggested that the Catawba River and its limited number of bridge crossings into Mecklenburg made access to Gaston’s land for development purposes more challenging than in other counties. Others have pointed to the sheer pervasiveness of the textile industry and the possible effect that might have had on efforts to diversify the county’s economy. Certainly, Gaston’s abundant rivers made the county ripe for the development of the textile industry during the 19th century to an extent not seen in any other county, and by the middle of the 20th century, nearly every incorporated town in Gaston, with the exception of the antebellum county seat of Dallas, owed its existence to a local textile mill. In fact, much of the county’s dramatic population growth around the turn of the 20th century was the result of the region’s last great wave of in-migration, when many people left the mountainous counties of the western Carolinas for what they perceived as better economic opportunities in Gaston’s mills.

Today, Gaston finds itself in a situation not unlike some of the great New England textile communities of the 19th century – places like Lowell, Massachusetts – that had to reinvent themselves economically after the industry that built them moved south. And like those older New England cousins, Gaston also finds itself with a remarkable architectural legacy left behind by that textile industry, a legacy that may in fact provide a glimpse into how the county might reposition itself in the Charlotte region for the 21st century.

Already, some of those former textile towns, such as Belmont and Mount Holly, are discovering that the old mill buildings, downtowns and residential neighborhoods that were built along the county’s picturesque rivers and “millponds” are proving to be attractive draws for newcomers looking to live and work near Charlotte, but in communities with more character and a sense of place than is typically found in some of the region’s newer residential developments. Even Gastonia, long perceived as moving forward at a sluggish pace, is showing promising signs of economic renewal with new restaurants and loft apartments in its historic downtown. And it isn’t hard to imagine that businesses looking for a good quality of life and lower costs might soon follow these residential pioneers.

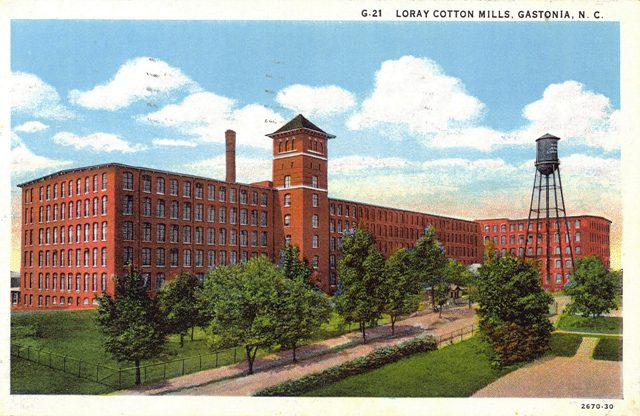

As Gaston looks ahead to the 21st century, it would be hard to find a more appropriate symbol of that future than in Gastonia, where the looming profile of the historic Loray Mill building is set against the silhouette of Crowders Mountain in the far distance. Loray, the subject of ongoing community efforts to save and restore it for adaptive uses, suggests an outlook that ironically includes both the shedding of the county’s old economic paradigm and the simultaneous use of that paradigm’s architectural legacy as one of the building blocks for an economic revival. Crowders Mountain speaks to a future that embraces the county’s great natural beauty and its close relationship to Gaston’s cultural history. In fact, it seems entirely fitting that Gaston has emerged as one of the early successes in the planning stages of the region’s new recreational trail initiative, appropriately named for the region’s textile heritage – the Carolina Thread Trail.

The Loray/Crowders image also hints at future clashes over preservation that seem inevitable once this sleeping giant of a county finally awakens from its long economic slumber. Already, the recent redevelopment of the old mill town of McAdenville has raised concerns about the potential loss of Gaston County’s textile heritage. As Gaston is re-discovered in the decades ahead and becomes one of the region’s next major growth corridors, many observers will be watching closely to see if Gaston can successfully balance growth and preservation, and in the process become the region’s best hope for preserving the rich textile heritage that helped make the entire Charlotte region what it is today. — Jeff Michael

Historic photo courtesy of the Gaston County Historic Preservation Commission. Other photos by Nancy Pierce

Gaston County links

Gaston County Articles & Publications