Lincoln County: An Introduction

Introduction: Until the widening of US Highway 321 into a four-lane, limited access highway was completed in 1998, Lincoln County did not feature prominently in the minds of many people in the Charlotte region. No interstate highways traversed the county, and while Duke Energy had created Lake Norman with the impoundment of the Catawba River at Cowans Ford in the early 1960s, the Lincoln County shoreline was better known for its modest summer cottages than the million dollar homes people associate with Lake Norman today. The county seat of Lincolnton served as Lincoln’s only incorporated town during this period (as it still does), and its economic and cultural life focused primarily on the county itself. With the official dedication of the new Highway 321 corridor in 1998, providing an alternative and less congested route between Interstates 40 and 85 than the Interstate 77 corridor further east, Lincoln became a hot prospect for industrial development. Coupled with the simultaneous explosion of residential growth in the Lake Norman area during this period, Lincoln County suddenly found itself emerging from its status as a regional afterthought to one of the hottest counties in economic development circles in the Charlotte region today.

Historical Overview: An excerpt from A Guide to the Historic Architecture of Piedmont North Carolina (UNC Press), Catherine Bishir and Michael T. Southern. (p. 444)

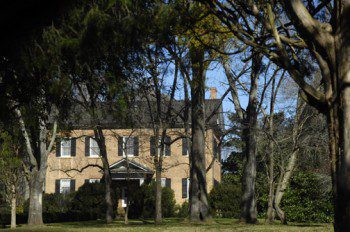

“Created in 1779 from Tryon Co. during the American Revolution, the county was named for patriot Gen. Benjamin Lincoln instead of the royal governor. At first encompassing territory from the big bend of the Catawba River down to South Carolina, Lincoln shrank as Catawba, Gaston and part of Cleveland Co. were carved from it in the 1840s. Its farmlands were settled mostly by Scotch-Irish and English near the Catawba River, Germans along the South Fork Catawba and its tributaries in the center and west, and a few French Huguenots. In the eastern section, related planter families – Grahams, Davidsons, Forneys, and Brevards – prospered from iron mining from the late 18th c. and took leading roles in the American Revolution and state politics. The county also claims the South’s first textile mill, built before 1816 by Michael Schenck and Absalom Warlick on McDaniels Creek; local mills remained small, though, until the late 19th c. A 19th-c. chronicler of the county observed, ‘No rural population in this county could boast of finer residences, both brick and frame.’ The county posses especially fine early 19th-c. brick houses with 3-room plans and variations and Flemish-bond brickwork. Their builders remain unknown.”

Lincoln Today: Lincoln County is one of the oldest counties in the region, having been founded during the American Revolution, and previously encompassing what is today all of Catawba and Gaston counties, and parts of Cleveland County. Similar to other regional counties with rich pasts, such as Anson and Chester, Lincoln’s history follows a familiar pattern: an early period of prominence as the civic and commercial center of a vast, sparsely settled area is followed by the subsequent loss of some of that territory as new counties are created by the state legislature to serve a growing population more effectively; in response to that loss, the county is soon overshadowed by upstart neighbors that more aggressively embrace the industrialization of the Piedmont, while the “mother” county holds on to a more rural way of life. Touring Lincoln County today, one certainly finds vestiges of this proud agrarian heritage, from stately homes built for planters in the early 19th century, to rural churches and “camp meetings” that played prominent roles in the histories of several Piedmont denominations.

To say that Lincoln entirely turned its back on industrialization in favor of a more agrarian future, however, would be unfair. Lincoln in the late 18th and early 19th centuries became the center of the Piedmont’s iron production, tapping into what is referred to as East Lincoln’s “Big Ore Bank”. Today, the ruins of old iron furnaces can be seen in this area, and even the name of one Lincoln community, Iron Station, is a reminder of the importance this industry played in the county’s early history. Another little known fact about Lincoln County is that the south’s first textile mill was built there in 1816, and while the county’s name never became synonymous with the textile industry in the same way that neighboring Gaston’s did, the county’s economy was nonetheless closely tied to the cotton mills that sprang up in places like Lincolnton and along the South Fork of the Catawba River.

Still, Lincoln County throughout much of the 20th century settled into a period of modest growth, and as interstate highways were built in neighboring counties, bypassing Lincoln’s rolling farmland, the county fell into a state of relative obscurity compared to Gaston, Mecklenburg and Catawba counties. The creation of Lake Norman in the early 1960s, rather than becoming the immediate growth magnet that it is today, served to further Lincoln’s sense of isolation (at least in its early days), as a huge swath of the county’s eastern border had been further removed from neighboring Mecklenburg, both physically and psychologically, by the broad, expansive waters of North Carolina’s largest man-made lake. The combined effect on Lincoln of these isolating forces was to reinforce its inward focus, and the pressure to adopt measures to prepare for Charlotte’s inevitable growth outward, which was being felt so urgently by other counties bordering Mecklenburg in the last quarter of the 20th century, never registered as a big concern for the county’s leaders.

The last decade has now changed all that. The widening of US Highway 321 has given the county direct access to two major interstate highways, and proactive measures on the part of the county, including the creation of the Lincoln County Industrial Park, have established the route as a significant manufacturing and distribution corridor. One of its more prominent corporate citizens is national retail giant Crate and Barrel, which in 2005 opened a major distribution center there. At the same time that Lincoln was being rediscovered for industrial development, residential growth in the eastern half of the county, around the Denver community, began to accelerate. This growth was fueled by Lake Norman, which became a leading choice in the Charlotte region for high-end, primary residences of retirees, as well as people working in Charlotte and other nearby employment centers such as Mooresville and North Mecklenburg. This transformation of Lake Norman from a weekend/summer cottage market to luxury primary residences suddenly changed the character of eastern Lincoln County and set into motion a flood of new development that continues to this day. Additional road improvements, such as the current widening of NC Highway 16 to four lanes, will only further that trend.

As this new growth continues, the biggest question for Lincoln today is whether or not the county is adequately prepared for it. Lincoln’s persistence as the only county in the Charlotte region with just one incorporated municipality says much about Lincoln residents’ attitudes toward government oversight. Recent efforts to incorporate some of the communities around Lake Norman in order to manage growth more effectively have been met with political resistance.

After years of maintaining a low profile in the Charlotte region, Lincoln County appears to be ready to reclaim a more prominent role for itself. In doing so, it will be interesting to observe in the years ahead whether Lincoln is able to reconcile its tradition of minimalist government with the enhanced expectations for more government that usually accompany growth. — Jeff Michael

Photos by Nancy Pierce

Lincoln County links

Lincoln county Articles & Publications