Mecklenburg County: An Introduction

Introduction: Mecklenburg County’s identity is inextricably tied to Charlotte, the region’s economic engine. Given the dominance of Charlotte, however, it’s all too easy to equate Mecklenburg County’s image entirely with the Carolinas’ largest city. To do so would be to diminish the unique identities of the county’s six other municipalities, and the important role those towns play – as the first set of “ring communities” surrounding Charlotte – in setting the course for future growth and intergovernmental collaboration for the entire region.

Historical overview: An excerpt from A Guide to the Historic Architecture of Piedmont North Carolina (UNC Press), Catherine Bishir and Michael T. Southern (p. 502-506)

[Mecklenburg was] settled in the 1750s mainly by Scotch-Irish Presbyterians and some Germans, the county and its seat were established in the 1760s and named for Queen Charlotte of Mecklenburg, the German-born wife of England’s George III. Charlotte prided itself on its early support of American independence with celebrations of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence, said to have been signed May 20, 1775. The trade-oriented town dealt in various crops, including grain and later cotton, and the 1799 discovery of gold in the area made it the center of the nation’s first gold rush and site of a U.S. mint (1837-61).

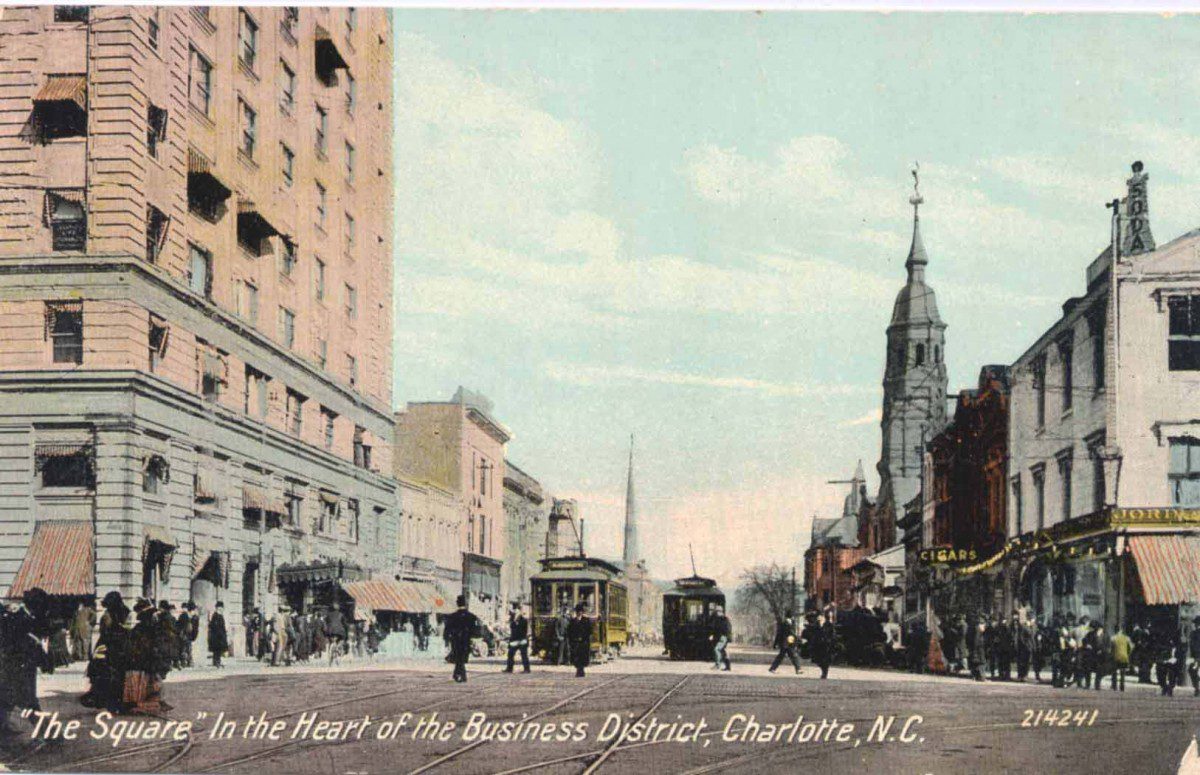

Charlotte is the largest city in the Carolinas, [with a 2009 population estimate of 913,639] and a center of a metropolitan region of [1.7 million (Charlotte-Gastonia-Concord MSA, 2008 estimate)]. A banking, manufacturing and distribution hub since the mid 19th c., the city epitomized the New South at the beginning of the 20th c. and is the New New South city at the beginning of the 21st c. Its architectural character reflects its spirit of enterprise and constant reinvention. As a 1907 publication proclaimed, ‘Charlotte does not hang back and wait for strangers to come in with their money and do things for it; it puts its money into things, shows the prospective investor what it is doing and bids him come in and do as well, or better, if he can.’ Generations of industrial plants and suburbs – including trend setting early 20th c. designs – spread out in chronological rings around a compact and continuously rebuilt city center that rises Oz-like above the trees.

In the 1850s Charlotte gained vital rail connections – the Charlotte & South Carolina Railroad (1852) from Columbia and the North Carolina Railroad (1854) across the state – that gave its cotton market competitive rates. During the Civil War, the rail town far from Union lines became the Confederate navy yard, and business rebounded after the war. Seizing the ethos of the New South, Charlotte attracted entrepreneurs who arrived from the Carolinas and elsewhere in pursuit of opportunity. New and old Charlotteans promoted business and invested in trade links – the Carolina Central Railroad to Wilmington (1872) and Atlanta & Charlotte Air Line Railway (1874) – that produced connections in six directions and the nickname “Queen City of the Piedmont.” With 7,000 people in 1880, it grew to 34,000 by 1910 to overtake Wilmington as the state’s largest city, ran a close second to Winston-Salem with 46,000 in 1920, then raced ahead with 82,000 residents in 1930 and 100,000 in 1940.

The 1881 Charlotte Cotton Mill opened the city’s campaign to “Bring the Mills to the Cotton!” as steam, then electric power freed mills from stream side sites. From the 1890s into the 1920s, Mecklenburg ranked among the state’s top three textile manufacturing counties. Some two dozen cotton mills sprang up in and around the city, each with its village. By the late 1920s more than 600 mills operated within a 100 mile radius of Charlotte, as the Carolina Piedmont surpassed New England in textile production. Rather than sticking with textile production alone, Charlotteans diversified the city’s economy to make it the financial, distribution, and electric power hub of the Carolinas – the “Industrial Center of the New South.” They began their own good-roads movement, then led in the state campaign, developed the city as a trucking center, and in 1926 build Wilkinson Boulevard to Gastonia, the first 4-lane highway in the state.

Downtown cotton brokers maintained offices in skylit rooms, while their goods filled long warehouses by the tracks. Industrialists built up S. Tryon St. as “the Wall Street of the South” to finance regional development. Textile machinery distributors the world over made Charlotte their southern headquarters, and it became the distribution point for everything from Coca-Cola and Lance snacks to popular music and schoolbooks. James B. Duke made Charlotte headquarters for the Southern (Duke) Power Co., established in 1905 to use the power of the Catawba River to industrialized the region, and brought Charlotte another title – “The Electric City.”

The early 20th-c. city essentially rebuilt itself. As it grew, its form like that of other cities was redefined by Jim Crow segregation practices and the transforming power of the streetcar (1891) and the automobile. At the center, Trade and Tryon’s business house and mansions gave way to the flagship shops of new regional department stores and ever taller skyscrapers, competing locally and with rivals in Greensboro and Winston-Salem. In the late 19th c., Charlotte’s citizens, about 60 percent white and 40 percent black, lived in dispersed patterns, with prominent white and black businessmen, doctors, lawyers, and city officials and their families residing within a few blocks of working-class citizens of both races. In the 20th c. class and racial patterns coalesced, first in a checkerboard pattern, then into larger sectors. At the city edges, textile villages grew more separate from the rest of Charlotte, especially on the north; the old wards became more predominately black as whites moved outward; black suburbs developed mainly in the northwest; and single-class, white suburbs reached into the countryside, with the most exclusive on the south and east. The first streetcar suburb, Dilworth (1891) repeated the mixed uses and grid plan, but soon Myers Park (1911) and others inaugurated restricted occupancy and curvilinear designs by nationally prominent planners John Nolen and Olmsted Brothers of Boston and Earl Sumner Draper of Charlotte. By 1926 the Charlotte Observer declared that “the population is moving outward and taking the city with them.

Despite the Great Depression, Charlotte’s diversification helped it survive downturns in cotton farming and textile manufacturing. At the end of World War II, the city stood poised for growth. Charlotte bankers strove to exceed Winston-Salem’s Wachovia as the Southeast’s leading bank and built skyscrapers accordingly. National patterns of highways, shopping centers, and suburbs coupled with urban renewal shaped the city’s population growth from 100,000 in 1940 to 200,000 in 1960 and more than 300,000 in 1980.”

Mecklenburg today: Mecklenburg County entered the 21st century having solidified its destiny as a truly urban county. The emergence of Charlotte as a prominent financial center with a national and even global reputation catapulted the county into the ranks of America’s major urban areas, with many of the same “big-city” amenities and challenges experienced by other urban counties in the United States.

The lessons in collaboration and growth management experienced by Charlotte and Mecklenburg’s other towns continue to set an example for how communities in the region might approach the complex issues associated with Charlotte’s expanding growth. The northern Mecklenburg towns of Huntersville, Cornelius and Davidson have zealously guarded their historic identities as independent towns while simultaneously (and aggressively) linking their future to Charlotte’s plans for commuter rail. The southeastern towns of Pineville, Matthews and Mint Hill, having experienced both the benefits and costs of the region’s first major wave of suburban expansion, are now reassessing their roles within the metropolitan region as growth now spills over into surrounding counties.

Mecklenburg County is unique among the region’s fourteen counties in that it is the first and only one to make a complete transition away from the familiar urban/rural divide that has historically influenced policy decisions in the region’s other counties. Any thought of retaining a balance between urban and rural environments in Mecklenburg was lost with the decision by county commissioners in the late 1980s not to implement a bond program, approved by voters, for the preservation of the county’s remaining farmland. Given the county’s rapid growth during this period, it’s questionable how successful such a program would have been anyway in preserving enough land to maintain agriculture as a viable economic activity. With the exception of a few preserved agricultural lands in the northern part of the county and scattered public recreation areas elsewhere, Mecklenburg is likely to be fully developed by the year 2030.

Policy decisions in Mecklenburg today turn more on issues associated with the urban/suburban divide, and debates about the nature of the county’s emerging urbanism. Economic discussions center on the issue of diversification and how to make sure that the county isn’t too dependent on the financial and service industries that fueled its recent growth, and as a safeguard against the potential flight of established businesses to surrounding counties where the tax burden is lower. Land use discussions no longer focus on issues of large-scale open space protection, such as farmland preservation, but instead on issues of density and the preservation of green space for a growing urban population. Transportation decisions have moved beyond just the issue of improving mobility, focusing more on the relationship between the county’s transportation network and its land use policies. And efforts to address social inequities within the community no longer revolve around the old black/white paradigm of years past, as the county’s dramatic growth has led to a more diverse and cosmopolitan population that is quickly redefining the old southern stereotypes about race and class.

In an often-quoted story about Mecklenburg’s history, the county initially developed around the crossroads of two ancient Native American trading paths that now make up the intersection of Trade and Tryon streets in downtown Charlotte. How fitting that today a community-wide initiative to encourage citizens to embrace the county’s growing diversity has adopted the word “crossroads” for its name. Known as Crossroads Charlotte, the initiative is built around a set of alternative scenarios for the county’s future that depend on critical choices being made today. Mecklenburg County is indeed at a crossroads between a period in its history where it once struggled to retain elements of its agrarian past in the face of rapid urbanization, and a brave new era where it has fully embraced an urban future but hasn’t quite figured out yet exactly what form that urban future should take. The economic, environmental and social well-being of the county, and in fact the region as a whole, depends on how successfully Mecklenburg County resolves that question. — Jeff Michael

Historic Photo courtesy of the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Charlotte Mecklenburg Library. Other photos by Nancy Pierce.

Mecklenburg County links

Mecklenburg County Articles & Publications