Stanly County: An Introduction

Introduction: For years Stanly County maintained a rather modest reputation within the Charlotte region. While blessed with amazing natural beauty, including Morrow Mountain State Park and a chain of beautiful man-made reservoirs along its eastern border, the lack of a major four-lane road connecting the county to surrounding urban areas and to the nation’s interstate highway system limited its potential for economic growth for much of the 20th century. Considered a curse or a blessing, depending on one’s perspective, this reality left the county largely unaffected by the economic and cultural forces that transformed large portions of the Charlotte region during the last two decades. With the recent widening of Highway 24-27 to four lanes between Charlotte and Albemarle, western Stanly County is now positioned to be one of the region’s next major growth corridors, helping to offset the loss of traditional manufacturing jobs elsewhere in the county, but bringing with it an entirely new set of challenges related to maintaining the county’s quality of life.

Historical overview: An excerpt from A Guide to the Historic Architecture of Piedmont North Carolina (UNC Press), Catherine Bishir and Michael T. Southern (p. 283)

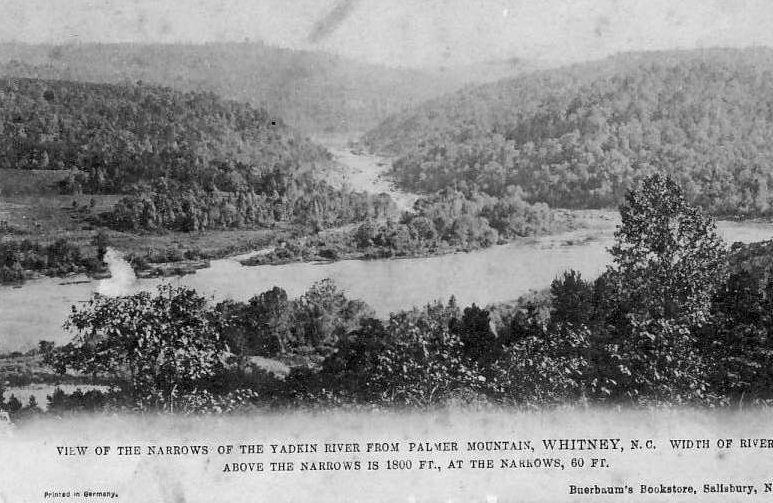

“The pleasant country retains many unspoiled rural areas with unpretentious farmhouses and agricultural buildings of many eras, as well as small towns recalling early 20th c. growth. The land on the west bank of the Yadkin River attracted settlers of English decent in the 18th c., while Germans from Cabarrus and Rowan counties gathered farther west and Scotch-Irish from South Carolina and the mid-Atlantic took up lands throughout the area. In 1841 Stanly Co. was formed from a portion of Montgomery Co. west of the river and named for New Bern politician John Stanly; it is one of several Piedmont counties strategically named for easterners. There were a few plantations along the Yadkin and Rocky rivers, but small farms predominated, long famed for good wheat and other grains. In the 19th c., gold mining enriched the area, with 11 mines in the county at one time. Potential river trade with South Carolina was impeded by the Narrows of the Yadkin, a rapids-filled gorge in the Uwharrie Mountains, and recurrent typhoid epidemics dashed several attempts at port toens below it. Town growth finally began with the late 19th c. railroads that encouraged textile, timber, and building supply industries. In the early 20th c., a major hydroelectric dam spanned the Narrows, and the aluminum-producing town of Badin was established.”

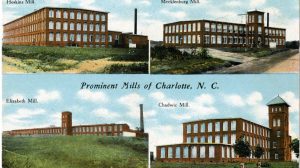

Stanly today: Long-time residents of Concord in neighboring Cabarrus County often point to Stanly County and its county seat of Albemarle as an example of what their community was like just twenty-five years ago before Charlotte’s sprawling growth dramatically altered its character. Albemarle and neighboring places such as Norwood, Badin, New London and Oakboro, have grown modestly, if at all, from the small to medium-sized towns that throughout the 20th century served as the commercial and civic focal points for what remains a largely rural county. For much of the past hundred years, textile and other manufacturing jobs supplemented agriculture to provide the economic fuel to sustain these communities, and while their proximity to Charlotte may have been an advantage in recruiting manufacturing firms and providing access to cultural and retail amenities for their residents, their big neighbor to the west didn’t factor significantly into their daily consciousness.

Stanly today: Long-time residents of Concord in neighboring Cabarrus County often point to Stanly County and its county seat of Albemarle as an example of what their community was like just twenty-five years ago before Charlotte’s sprawling growth dramatically altered its character. Albemarle and neighboring places such as Norwood, Badin, New London and Oakboro, have grown modestly, if at all, from the small to medium-sized towns that throughout the 20th century served as the commercial and civic focal points for what remains a largely rural county. For much of the past hundred years, textile and other manufacturing jobs supplemented agriculture to provide the economic fuel to sustain these communities, and while their proximity to Charlotte may have been an advantage in recruiting manufacturing firms and providing access to cultural and retail amenities for their residents, their big neighbor to the west didn’t factor significantly into their daily consciousness.

Today, the decline of Stanly County’s traditional manufacturing base, coupled with recent improvements in highway access to Charlotte, have positioned the county for an historic transition, both in its fundamental economic structure and its physical landscape. Abandoned textile mills are scattered throughout the county, reflecting the general fate of the Carolina textile industry, while the rusting mass of the shuttered Alcoa smelting plant in the town of Badin (where over a thousand people were once employed) is a reminder of how global economic forces have converged to affect entire communities in the region. Because of these blows to the county’s traditional manufacturing base, Stanly County’s current economic fortunes are as dim as they have been in many decades. And yet, on the western edge of the county, a beam of hope is emerging in the development of the new Locust Town Center, a symbol of the coming influence of the Charlotte region’s growth on Stanly County, and an early indication of how it might respond to the challenges that growth will bring.

The combined impact of the recent widening of Highway 24-27 to four lanes and the opening of the eastern leg of Interstate 485 just ten miles west of the county line has made the western part of the county more attractive for commercial and residential development. In particular, the Town of Locust is representative of the kinds of dilemmas faced by communities throughout the region that are in the path of the region’s “progress”. What had existed for nearly a century as Locust’s “downtown” – a modest strip of commercial buildings along Highway 24-27 – was demolished to make way for the widening of the highway to four lanes, a terrible price that many local leaders were nonetheless willing to pay in order to provide the economic lifeline that such a highway could bring to Stanly County. In response to this loss, a group of investors – supported by the town and employing the nationally-recognized design firm of Duany Plater Zyberk – proposed to build a new commercial and civic center, surrounded by pedestrian-friendly residential neighborhoods, to replace the downtown that Locust had lost.

While still under construction, the Locust Town Center project has emerged as a mixed-use development that incorporates many of the guiding principles of “new urbanism”. A bold response to the kinds of low-density development characteristic of surrounding high-growth areas in neighboring counties, local leaders have gone on record as stating that they hope the Locust Town Center will serve as a model for other developments and set a standard for a different kind of growth as Stanly County prepares for the next wave of the Charlotte region’s outward expansion. Whether or not the political will-power will be there to enact the sort of land use policies necessary to build upon the Locust Town Center model is yet to be seen.

Even as Stanly County prepares for an economic boost from the region’s continued growth, it also has an opportunity to preserve some of the remarkable natural and cultural amenities that give it a distinctive character. While many communities talk about heritage-based and nature-based tourism, Stanly may be one of the few counties in the region that truly has the core ingredients to carve such a reputation out as a viable niche serving the Charlotte market: an amenities-rich state park at Morrow Mountain that serves as a gateway to the Uwharrie National Forest, a chain of beautiful man-made reservoirs along the Yadkin-Pee Dee River, numerous small towns that have retained their historic character, and a picturesque rural landscape that already attracts cyclists from nearby Charlotte on a regular basis. How the county balances the inevitable growth coming from Charlotte with the preservation of these natural and cultural resources will go a long way toward determining whether maintaining such a niche is indeed possible. — Jeff Michael

Historic photo courtesy of the Stanly County Museum. Other photos by Nancy Pierce and Jeff Michael.

Stanly County links

Stanly County Articles & Publications