Car-free Life for a Family of Four in Delft, Netherlands

Charlotte-based architect and urban planner Martin Zimmerman talks with Melissa and Chris Bruntlett about their latest book and their family’s first few years living and navigating Delft, a 1,200 year-old city in the Netherlands, mostly by bike, at speeds rarely exceeding ten miles per hour.

To the casual tourist, this human-scaled city of 104,000 calls forth memorable associations with the past: narrow canals with flowered embankments, world-renowned Delftware ceramic factories, and the oeuvre of 17th century Dutch Master Johannes Vermeer. But Delft is also about present and future, with avant garde architectural projects, TU Delft — a first-rate university with 24,000 students — and a sustainable transportation system.

It’s where a morning commute on the Nederlandse Spoorwegen rail to downtown Rotterdam takes less than 15, low-carbon minutes. At the other end of the transport spectrum, moving about by foot or bicycle is an egalitarian, intergenerational activity shared by everyone from preschoolers to golden-agers. Daily trips by cycling are estimated by some surveys to be as high as 35% of the transport pie. And that’s just a portion of Delft’s impressive mobility menu.

MZ: In your new book Curbing Traffic – The Human Case for Fewer Cars in Our Lives, you share a fascinating account of your family’s newfound freedoms. It all began in 2019, when you left Vancouver, BC, one of North America’s greener cities, with your children, Coralie and Étienne, in tow. What compelled you to move, and how did landing in Delft affect your family?

MB/CB: The choice of Delft was quite happenstance. When planning our initial trip to the Netherlands in 2016, it was not even on the list of cities that inspired our first book, Building the Cycling City: The Dutch Blueprint for Urban Vitality. We knew we wanted to downsize our lives, we wanted to live car-free, and we wanted to trade the bustling streets of a major city for the quieter space of a smaller town. Delft was the location of both of our employers, and we needed to be closer to our childrens’ schools. Its more advanced travel network meant we could get a bigger dose of the quality-of-life aspects we loved about Vancouver.

MZ: Your book is structured along the lines of rudimentary mobility themes viewed from the users’ perspective. There’s the feminist city, climate resilient city, city for seniors, trusting city, and child-friendly city. Speaking of child-friendly, if parents aren’t hustling their children around town in the backseat of a car, does that mean kids spend less time playing computer games on their tablets or iPhones?

MB: We’re careful to avoid suggesting our no-car life automatically guarantees kids spend less time on screens, but by the time most Dutch children are eight or nine years old, parents are comfortable letting them travel independently. And lots of kids under five get bicycle training in preschool. They learn how to assess risks and interact with people outside their proverbial home-based bubble or the shell of their parents’ car. Autonomous mobility by foot, bicycle and public transit is a great proving ground for later adult life.

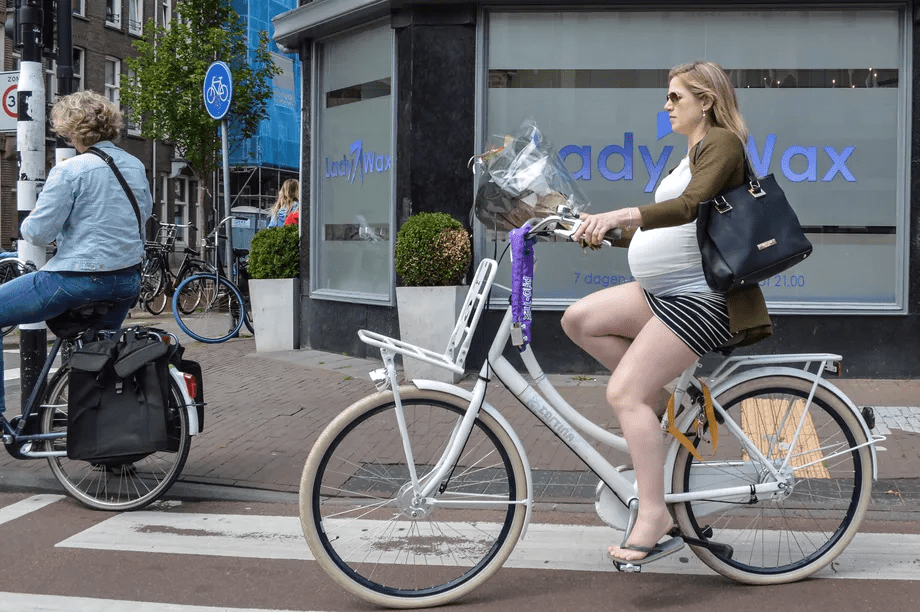

No helmet, no spandex, no gloves. It’s the norm in Delft and other Dutch cities. Credit: Mondacity.

MZ: In the feminist city, you argue in favor of street design which supports the care work of women, especially mothers like yourself. What is “care work” and how has Delft tackled this challenge?

MB: Care work is unpaid work to provide for the daily needs of others. Grocery shopping, taking kids to school, looking after elderly family members, are still done mostly by women. It all adds up. Street connectivity in Delft makes it pretty easy to take on these tasks by walking or cycling. It makes the act of “trip chaining” — connecting several shorter stops into a complete journey — almost seamless. The result is more time to share with loved ones and pursue pleasurable activities.

MZ: There’s another notion you cite called “forgiving design.” What does that mean, and what does it imply?

CB: Forgiving design is one of the five principles of Dutch Systematic Safety. DSS is predicated on the idea that to err is to be human. In terms of traffic, it means that even if folks make mistakes, crashes can still be avoided. Forgiving design minimizes the probability of harm — especially to the most vulnerable — children, the elderly, the deaf and blind and others with infirmities. Protections at heavily trafficked intersections, adding mid-block crossings for cyclists and walkers, speed bumps, moveable bollards and textured surface treatments are just some of the design treatments that work well.

MZ: How do children’s mobility needs overlap with the needs of senior citizens? Are there qualities that distinguish the two?

MB: While many of the elements that shape the environment for children benefit our seniors, and all citizens, there are certain design details which need to be considered for elderly populations. The most often overlooked is seating. We move slower as we age, and our endurance and the distance we can comfortably walk in one journey is shortened. Providing seating along frequently traveled routes allows senior citizens to stop and rest, enabling them to continue their journey independently.

Frequent social interaction is incredibly important as we age. Seniors need to interact with their neighbors and breathe some fresh air. The simple act of sitting on your front stoop everyday and waving to neighborhood children on their way to school enhances your quality of life, especially in your twilight years.

Freedom of access by electric tricycle and guide dog. For the elderly or the blind. Credit: Mondacity.

MZ: What about the elderly who choose to live in a seniors setting? Does Delft’s travel environment have a place for them?

CB: Delft is home to a number of seniors’ communities. They are located along traffic-calmed streets, near grocery stores, social agencies, community centers and other services. Those capable of traveling with or without a mobility aid can partake of street life and activity just as much as anyone else.

MZ: In 1971, a spirited cadre of residents along Delft’s narrow Tuinstraat (Garden Street) took matters into their own hands to keep cars at bay. The result was dubbed a woonerf, i.e. “living street,” and its popularity has spread worldwide. Talk about the woonerf and why it’s gotten so much attention.

CB: Woonerven are specific treatments applied within Dutch neighborhoods to give pedestrians priority over cars. Maximum car speeds are set at 15kmh (10mph), although added design details often force speeds down to 4mph, or walking speed. Typically, curbs are removed, the road space is realigned from a straight throughway to one with varying widths, and amenities such as play equipment or bicycle parking are grouped in the middle of the street.

The end result is an outdoor living room where it’s quiet enough to hear the “who-who” of a long-eared owl perched on a rooftop.

Tuinstraat woonerf. Where the car is limited, but kids playing kickball are not. Credit: Martin Zimmerman, City Wise Studio USA.

MZ: Do you think the post-World War II invention of the suburban cul-de-sac qualifies as a valid form of woonerf?

CB: It’s a false equivalency, and for several reasons. Their excessive street width encourages auto dominance. Driveways at every house pose an additional conflict. Perhaps worst of all, cul-de-sac neighborhoods lack the fundamentals of a basic sidewalk or bicycle network. This forces pedestrians to walk in the street and cyclists to outmaneuver the car. I’d hate to rely on a wheelchair and be confined to a cul-de-sac.

MZ: According to city records, a central market was first established in Delft’s Markt square in 1246 A.D. After World War II, with auto ownership and consumer demand for parking in the city’s core areas on the rise, the square’s fate took an appalling turn for the worse in the form of a mammoth parking lot. Surprisingly, it took until 2003 to overcome vigorous push-back from local merchants and restore historic status to the square. Can you describe how the battle for car-free space was won?

MB: Because the adjoining merchants feared year-round outdoor cafes and kiosks wouldn’t attract enough customers, Markt square’s renewal began with a pilot project where a fraction of the space would be transformed to walkable uses, while maintaining the remainder as parking. After pedestrians and cyclists flocked back to the square in huge numbers, the businesses had a change of heart. A similar conversion process took place in nearby Beestemarkt and Doelenplein squares. Delft residents and scads of tourists continue to eat, drink and shop in these squares. We can’t imagine returning to the hostile, car-choked environments of the past.

Free parking in Markt square, circa 1960s/70s. Credit: SERC.nl.

Car-free Markt square – 2022. On Thursdays it’s jam-packed with farm-to-table food vendors, pop-up cafes and colorful florists’ booths. Credit: Wikipedia.

MZ: Are e-bikes making much headway in Delft or other Dutch cities?

CB: The proliferation of e-bikes in the Netherlands has been immense. We have the highest sales of e-bikes per capita in the world. Although of greatest benefit to the elderly, e-bikes are used by all age groups. And we use all types of bikes — three or even four-wheeled bikes.They are incredibly powerful tools to enable longer-distance cycling and to haul large loads, groceries, toddlers, household pets and the like.

MZ: How did the Dutch react to the 2020 pandemic lockdown when it was impossible to get back to normal?

MB: While many North American cities scrambled to reallocate road space for “slow streets,” “pop-up” bike lanes, and temporary outdoor dining districts, the streets of Delft remained relatively unchanged during lockdown. Having taken aggressive government action to reallocate street space in response to the OPEC oil embargo of 1973, Dutch communities were ideally positioned to weather the Covid-19 shock without tinkering with added design changes. The overarching principle: build resiliency into the system to meet unforeseen crises.

MZ: Traffic behavior in the USA is drastically different from the Netherlands, possibly hinting at a deep cultural divide between America and her Dutch counterparts. And it’s getting worse, not better. During the Covid pandemic, North Carolina’s speed-related fatalities reached their highest point in more than a decade, despite fewer cars on the road.

Looking at mode-share metrics over the long-term reveals another stark contrast. Combined mode-share for daily cycling and walking trips in U.S. and Canadian cities have rarely surpassed 4% of daily trips, but in Dutch cities it’s consistently been 35% or more. With this vast difference in travel choice, do you see any hope for North American cities to tame the car on par with Dutch?

MB: We do see hope for North American cities, but it isn’t an easy fix. Even the equitable transport environment we enjoy in the Netherlands has not always existed. It took over five decades of brave political, policy, planning and design decisions to rethink our relationship with the car. Today we see former car-dependent cities like Rotterdam (whose city core bears a striking similarity to Uptown Charlotte) reducing motor vehicle lanes and using the regained space for walking, cycling, parklets, plazas and other civic design enhancements. It all boils down to the principle of shared streets as public spaces instead of motor traffic arteries.

Rotterdam’s Centraal rail station plaza (lower left), built in 2014, merges seamlessly with an auspicious tree-lined promenade stretching for several blocks within the heart of downtown. Note: 1) tramcar access (mid-left), 2) pavilion and elevator to underground parking for bikes and cars (center-right), 3) 2-way, buff-orange cycle tracks overlapping with supersized crosswalks. Other than Manhattan’s Times Square upgrade and San Francisco’s Embarcadero Ferry redevelopment, too few U.S. downtowns can trumpet this stunning urban design success story. Credit: Martin Zimmerman, City Wise Studio USA.

Netherlands’ response to Covid provides hopeful evidence that shared streets are possible elsewhere, including Charlotte and her sister cities in North Carolina. With COP26 and the climate crisis weighing heavily on the public conscience, obesity rising at an alarming rate, and spiking traffic fatalities, leadership should be acting boldly to reconfigure the public realm in alignment with other basic essentials for human survival, including health, safety and climate mitigation.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

The author’s car-free explorations of European cities have included Malmö, Sweden, Copenhagen, Brussels, the Dutch cities of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Delft, and elsewhere in the U.K., France and Germany. Martin lives “car-lite” near the JW Clay rail stop in University City.