Our population is more concentrated in cities — and increasingly diverse

There’s a common narrative about people in rural areas seeking opportunities: they should go to the big city and leave the country behind.

Rural counties are often seen as hollowed out or in decline, while cities and their adjacent suburbs boom. While population in the Carolinas Urban-Rural Connection study area has become much more concentrated in the urban and suburban core, the story is (as usual) more complex than that.

Population change in the region over time

The region’s population has grown steadily, but the sharpest increase has occurred in the past 30 years. Between 1990 and 2000, the population grew from 2.5 million to 3.1 million, adding nearly 600,000 people, or almost 25 percent, in just one decade. The next decade saw similar growth, adding another 600,000 people to reach a population of 3.7 million. As we near the close of the 2010s, Census population estimates put the region’s population at a little over 4 million.

The Carolinas Urban-Rural ConnectionA special project from the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute |

|---|

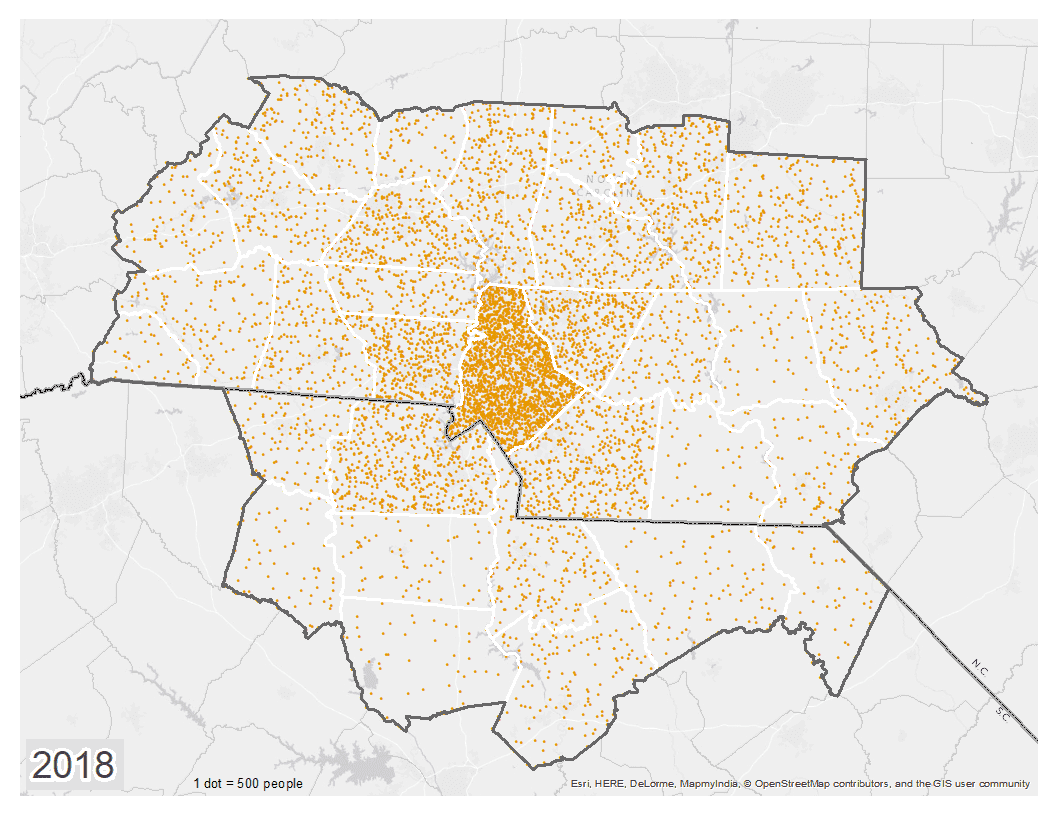

As population growth in the region has accelerated in recent years, it has also become more concentrated in the region’s urban core (Mecklenburg County) and the adjacent mixed-urban counties (Cabarrus, Gaston, Union, and York).

In 1900, Mecklenburg accounted for just 7 percent of the region’s population, while more than half of the population was scattered among the mixed rural counties, and a fifth each in mixed-urban and rural counties.

In 2018, over a quarter of the region’s population was found in Mecklenburg County, the same as all the mixed-urban counties combined, while only 6 percent of the population was in rural counties. Mixed-rural counties as a group still account for the largest share, with just under 40 percent.

For an illustration of this trend, click on the picture below to view an animated map.

This concentration is the result of growth in the urban and mixed urban counties combined with population loss in several of the region’s rural and mixed-rural counties. Four counties (Anson, Fairfield, Marlboro, and Union, S.C.) reached their peak population in the early-to-mid 20th century and have been mostly on the decline ever since. Another seven counties started to experience population decline in 2010.

However, more than half of the mixed-rural counties have continued to grow since 2010, while three of the region’s rural counties have gained population: Polk, Alexander, and Davie.

What’s driving recent population change

Population change occurs in two fundamental ways: natural increase/decrease (the difference between the number of births and deaths in an area) and net migration (the difference between the number of people moving into and out of the area). Both of these forces are at play in our 32-county region, but migration is stronger.

- In most counties that have lost population since 2010, net out-migration (more people moving out than in) is the driving factor, accounting for about 90 percent of the population loss in many of these communities. A handful of counties in the Foothills region experienced natural decrease but net in-migration, which helped mitigate total losses. In Polk County, for example, the net in-migration of 1,300 people offset the natural decrease of 1,200 and kept the total population change slightly on the positive side.

- Net in-migration (more people moving in than out) is the predominant force in nearly all of the counties that have grown since 2010. Randolph was the only county in which natural increase was the primary source of population growth. In all of the other growing counties, net in-migration accounted for the majority of population growth, ranging from 59 percent to 99 percent of the total.

- In the region’s rural counties, about 60 percent of recent population loss is due to natural decrease, while a little under 40 percent can be attributed to net out-migration.

- The opposite is true for the urban county, Mecklenburg, in which 60 percent of recent growth is attributable to net in-migration and 40 percent to natural increase. The region’s mixed-urban counties saw even greater net in-migration, accounting for 80 percent of recent population growth.

- Mixed-rural counties show the most variation. As a whole, they saw negligible natural increase, with net in-migration accounting for virtually all growth. However, the story varies considerably by county. In Marlboro, Richmond, and Union, S.C., for example, the majority of population loss was due to net out-migration. But in Caldwell, Rutherford, Burke, and Cleveland, natural decrease was the driving factor in population loss, and net in-migration hedged against further loss. Among those that gained population, net in-migration was the predominant force for all but Randolph County, which saw greater natural increase.

Where are these migrants coming and going?

In most of the region’s counties, domestic migration (people moving to/from other places in the U.S.) accounts for most of the change.

- About 60 percent of domestic migrants who moved to the region came from outside the Carolinas. Meanwhile, 52 percent of those who left the region moved somewhere else in North Carolina or South Carolina.

- Florida and New York are the top states people are leaving to move to the region, followed by Georgia and Virginia.

- For people going the opposite way and moving out from the Carolinas, Florida is also the top destination state, followed by Georgia, Virginia, and Texas.

- Immigration also plays an important role in several of the region’s counties. The majority of net in-migration in Burke and Cleveland came via immigration, which also accounted for about half of in-migration to Catawba and almost 40 percent in Mecklenburg. And several of the counties that lost population overall experienced net positive international migration in the midst of domestic out-migration. The largest source of international in-migrants in the region is Asia, accounting for 41 percent. Latin America is second, with 25 percent.

Age

Like the United States as a whole, the region is aging. The proportion of the population over age 60 increased from 16 percent in the year 2000 to 26 percent in 2018. The median age in all 32 counties increased, with an average increase of 5.6 years. Polk County has the highest median age, at 53.6 years, while Mecklenburg County has the youngest median age, at just over 35.

Since 2000, rural and mixed-rural counties have aged more rapidly than urban and mixed urban counties. In mixed-rural and rural counties, the population over 60 makes up 26 percent and 28 percent percent of the population respectively, compared to 16 percent and 20 percent for urban and mixed-urban.

Rural counties can become older by attracting retirees in search of scenic or lifestyle amenities, as is the case in Polk County, or by losing young adults to out-migration, which has happened in counties like Anson. In all 32 counties in the region, the growth of the share of the population over age 60 outpaced overall population growth.

This increase in the share of older adults corresponds to a smaller share of working-age adults (20-60). The share of working age adults primarily reflect in-migration and out-migration patterns, with some rural counties seeing an increase in population, but decrease in working aged adults, while others held steady or saw a decrease in both population and share of working age adults.

Of the eight rural counties in the region, Davie was the only one to see an increase in both population and working aged adults. Six of the 18 mixed-rural and all of the mixed-urban and urban counties saw an increase in population and a share of working-age adults that largely tracked population growth.

Racial makeup

The region has grown more racially diverse in recent years. The white population has decreased, from 75 percent of the population in 2000 to 66 percent in 2018. Urban and mixed-urban counties saw the greatest increase in minority populations.

- In Mecklenburg, the white population decreased by 15 percent from 2000 to 2018, followed by 10 percent in the adjacent Gaston.

- Catawba County, home to the Hickory micropolitan area, saw the greatest increase in minority population, with black and Hispanic populations each increasing by 6 percent in the past 18 years.

- The greatest increase has been among the Hispanic population. In Mecklenburg, the population doubled between 2000 and 2010, from 6 percent to 12 percent. Hispanics make up 14 percent of the population there today.

- Rural and mixed rural counties also saw an increase in the Hispanic population, albeit a much smaller one, averaging 3 percent. However, there is a lot of variation, with Randolph and Montgomery counties having populations that are 12 and 15 percent Hispanic. Much of this growth took place between 2000 and 2010, and has hence slowed.

Conclusion

Changes in demographic trends are driven by in-migration, out-migration, births and deaths. While these processes may look very similar statistically, and result in counties that have similar profiles, they reflect a wide variety of economic factors and circumstances.

Population growth, or the lack thereof, has tremendous impacts on the vitality of a place. An influx of older adults can provide both new opportunities and challenges in the region, while the share of working age adults greatly impacts the labor market. The region as a whole continues to be a dynamic place.