Plenty of big ideas are still on the table for Charlotte’s future

It’s been a tough year already for big ideas in Charlotte.

First, the city’s ambitious goal of a referendum for a 1-cent sales tax to fund a massive, $8 billion to $12 billion transit and mobility plan was thrown into question after worries emerged about whether the legislature would let it on the ballot and Census delays will likely nix elections this November. Then, the 2040 Comprehensive Plan — Charlotte’s first citywide planning effort since 1975 — ran aground on opposition to proposed changes that would allow duplexes and triplexes on most residential lots, as well as developer concerns over the mention of inclusionary affordable housing zoning and impact fees.

For people hoping to see Charlotte make big moves towards greater density, multimodal transit and a new, more urban vision of the city, it’s been a dispiriting few months. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t still a lot of big ideas swirling around — though whether any of them happen or not is, as always, an open question.

On Monday, City Council got an earful on the latest plans: A presentation from Charlotte Center City Partners about the latest draft of their 20-year vision for uptown (separate from the city’s overall plan, yet meant to tie in together), and an hours-long public hearing on the city’s 2040 comprehensive plan (a vote on which has been delayed until at least June). And on Wednesday, regional planners presented another vision of a more unified transit system around Charlotte. Here’s a look at five big ideas that are still kicking, and what obstacles might stand in their way.

Eliminating single-family-only zoning

The big idea that’s gotten by far the most attention in Charlotte’s proposed comprehensive plan is eliminating rules that only allow single-family, detached houses on about 84% of Charlotte’s residential land. The proposal would allow duplexes and triplexes anywhere in the city, with quadraplexes on main thoroughfares.

Those in favor point to neighborhoods like Myers Park, Dilworth and Elizabeth — expensive enclaves with lots of duplexes, triplexes and quadraplexes mixed in — and say updated regulations will allow more housing to be built at a time when inventory is at historic lows.

Opponents have raised concerns about fueling more gentrification if developers tear down single-family homes to build duplexes in older neighborhoods, as well as fears of more density changing the character of established neighborhoods.

A quadraplex in Elizabeth. Photo: Chuck McShane

Will it happen?

At a three-hour-plus hearing on Charlotte’s proposed plan (the city’s first comprehensive plan since 1975), about 100 opponents and supporters of the new regulations spoke. City Council has pushed back its vote on the 2040 plan until June, and staff plan to review comments and incorporate them into a new version of the plan to be released in the coming months. Single-family-only zoning regulations, as the source of the most passionate comments for and against, could be the part of the proposal that sees the most changes.

[Opinion: Charlotte wakes up to its future]

A new park on “capped” I-277

If uptown Charlotte planning had a “greatest hits” set list, this one would be on there. The idea of building a “cap” over the southern part of I-277 — a trench that separates uptown and South End like a wide river of rushing traffic — has been batted around for years now, including in iterations of the Center City Vision Plan since the 1990s. Charlotte Center City Partners CEO Michael Smith acknowledged Monday that it might sound like “a pipe dream” at this point, but pointed out that plenty of other cities have figured out how to build walkable parks and put other buildings atop otherwise wasted freeway space in the middle of their downtowns. From Dallas to Seattle to Pittsburgh, the idea has been gaining popularity.

“There are other cities that are in our peer set that have been able to do this quite well,” Smith said.

A rendering of I-277 before and after a freeway cap park is built. Charlotte Center City Partners.

Will it happen?

Capping 277 and building a park would require three things: Local will, coordination with the N.C. Department of Transportation, and money. Of the three, money might be the biggest obstacle. Costs can vary dramatically depending on size and location: A 5-acre freeway cap park in Dallas cost $110 million, while a 38-acre freeway cap park planned atop the Hollywood Freeway has an estimated price tag of $1 billion.

A regional transit system

The 1-cent sales tax referendum in Mecklenburg County is almost certain to be delayed for a year (if the legislature allows it on the ballot at all, that is), but that doesn’t mean moves aren’t happening towards a more integrated transit system. The Centralina Regional Council and the Charlotte Area Transit System have been studying the issue as part of the Connect Beyond regional transportation initiative.

They’re proposing a region-wide bus system that would include a unified fare system, a regional transit system website, tools to plan travel using different bus systems across the region, and “strategic transfer points with coordinated amenities.”

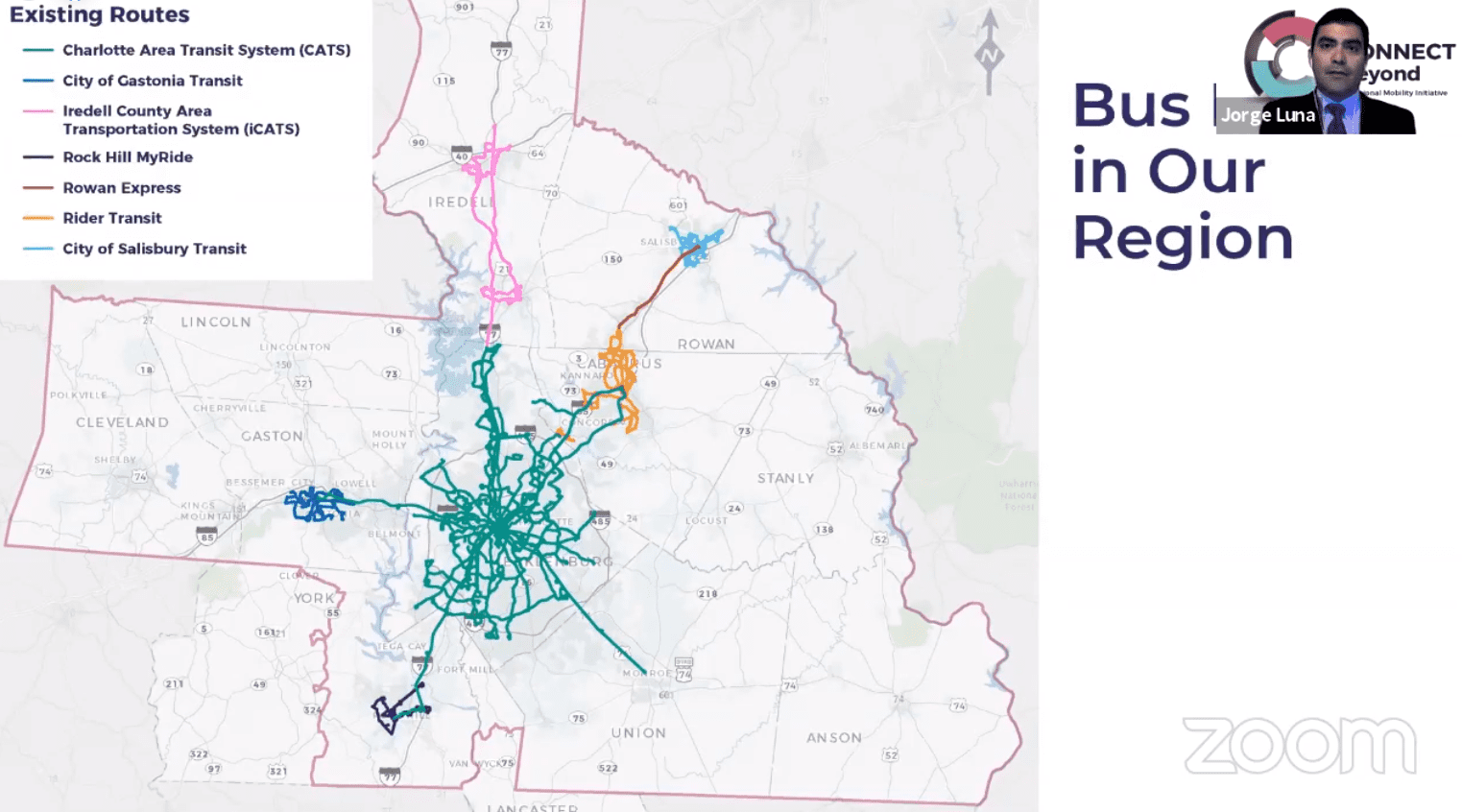

That would be a big first step for a region where counties have long operated their own transit systems. Currently, 17 transit systems exist throughout the region (though only six, such as Gastonia Transit, Rider Transit of Concord and Kannapolis and My Ride Rock Hill offer fixed-route services), and they all operate independently from CATS, with their own hours, fare systems, routes and frequencies. CATS offers only limited express bus service to other jurisdictions on its express buses.

That makes it especially hard for riders who might want a way to get across the region without a car. For example: at a presentation Wednesday, transit officials told the Centralina Regional Council that getting from Salisbury to Charlotte Douglas International Airport would take four hours, with six buses and four transfers using different fare systems. And that’s just one-way.

Regional Transit Systems often don’t tie together or coordinate. Centralina Regional Council.

Will it happen?

Coordinating with multiple jurisdictions across different counties, as well as coming up with unified bus service standards, could be a challenge. There was no funding source outlined at Wednesday’s presentation. And without a regional revenue source like a transit authority, each jurisdiction would potentially be left to fund its own systems and meet the new standards. Still, if it’s not cost-prohibitive, coming up with a single fare, coordinated transfers and locations where it makes sense to switch from one bus system to another could make it much easier to travel from county-to-county without a car.

A Queen’s Park instead of a rail freight yard

Just north of uptown, Norfolk Southern operates a major freight rail yard on what would otherwise be prime land for development. A grassroots effort to turn that into “Queen’s Park” — a 220-acre park that could be the large, public central gathering place Charlotte mostly lacks — is underway, and it’s a big picture idea in the Center City Vision Plan.

A rendering of a possible Queen’s Park. Charlotte Center City Partners presentation.

Will it happen?

Although Norfolk Southern said in 2012 that it planned to replace the centrally located railyard with its new facility at Charlotte Douglas International Airport, there haven’t been any concrete moves towards that. And as the Red Line impasse shows, railroads are especially reluctant to give up their access to real estate and rail tracks.

Smith acknowledged Monday that Queen’s Park might be a long way in the future.

“While this might be a longer horizon, we’ve got to take the first step,” Smith said. “Imagine how powerful Piedmont Park is to Atlanta.”

Making our “main streets” pedestrian-only

Should major uptown streets be closed to cars and opened to people? That’s a question city planners have dipped their toes in recently, closing part of South Tryon Street for several months to allow a Black Lives Matter mural on the street, and pandemic-inspired plans to open up more areas for street dining. The Center City Vision Plan will call for more such measures, Smith said, such as pedestrian-only parts of Tryon Street and Brevard Street. That would replace cars and parking with more space for people to walk, eat and gather.

“We can transform Brevard Street into this authentic, lively visitor destination,” said Smith. “Tryon Street is…the region’s Main Street and our civic gathering place. The last time it was reimagined was 1985. So, now is the time to produce a new plan to reimagine Tryon Street.”

A rendering of Tryon Street reimagined as a pedestrian-only plaza. Charlotte Center City Partners presentation.

Will it happen?

The Tryon Street pedestrian-only experiment ended rather abruptly last year, and cars are back on the road. The biggest obstacle to this idea isn’t cost (putting up some bollards and new paint isn’t that expensive), but expectations about where cars can go and worries from businesses and residents about losing access to parking. Getting community buy-in and the political will for a plan like this would be the major challenge. Or, as Smith put it: “It will take a comprehensive, broad, community engagement effort to create this amazing, welcoming place for all.”